It's now over a year since OVHcloud's SBG2 data center in Strasbourg was destroyed by fire. Legal wranglings over responsibility and compensation continue - and there is still no official public verdict on what actually happened.

This should be no surprise. The data center sector is shockingly bad at reporting transparently what happens in incidents. To take one example, when British Airway's data centers failed in 2017, it lost £58 million ($75m) in business over a holiday weekend. Any hope that we would ever be told what happened was quickly dashed. BA and its data center partner CBRE went to court, blaming each other two years later, they made a secretive financial settlement, in which neither admitted any fault.

At some point BA CEO Willie Walsh coyly admitted there was "human error." And that was all we heard.

Not really good enough

It's often remarked that if one of BA's aircraft had crashed, we'd have quickly had results from the "black box" recorder, following a clearly-defined procedure. No such procedure exists in the data center world, despite brave efforts to set up initiatives like DCIRN (the Data Center Incident Reporting Network, which has been somewhat quiet of late).

And commentators have regularly pointed out that, without full reports on the causes of failure, this industry is doomed to repeat them.

How likely is it that the OVHcloud disaster will follow a similar trajectory of secrecy?

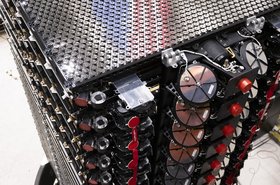

To its credit, in the immediate aftermath of the incident, the French cloud provider was comparatively open about the incident. In the days after the disaster, OVHcloud founder Octave Klaba and CEO Michel Paulin made a series of videos. Klaba revealed that the fire took hold in the UPS systems of SBG2, and talked about upgrading the company's cloud structure to provide the kind of availability zones available at AWS.

The company issued public updates on the physical process of clearing and rebuilding its services. It detailed what compensation customers would get, and it promised to fund a lab dedicated to studying fire prevention.

Clamming up

Then in May, it clammed up. The company announced it would be unable to reveal the cause of the fire until 2022. We are now nearly one-quarter through 2022, there's no sign of a report, and OVHcloud has not given any date for the report. The company's explanation is that its hands are tied. It is apparently unable to tell us what caused the fire until details are cleared with its insurers and government agencies.

To put this in context, we've been waiting more than a year now, and that is a very long time for an outage report which doesn't face the kind of wranglings that obscured the BA outage. Government involvement needn't slow things down: when a November 2017 failure caused a three-hour outage at the Singapore Stock Exchange (SGX), the Singapore government was involved, but the report was given to SGX in four months (the following March), and published in seven.

It's hard not to feel that OVHcloud would simply prefer to change the subject, and forget all about the incident.

Since then, Octave Klaba has said nothing further about the incident. He's been busy developing a gaming business, while OVHcloud has preferred to talk about new services that it seems to launch at an ever-increasing rate, including a Nutanix based private cloud, a PaaS service, an object storage service, and new bare metal servers.

This week, news emerged that OVHcloud is involved in an antitrust action against Microsoft. The action has been underway since September last year, and argues that Microsoft is abusing its position in the cloud, where it is strong, but not the dominant player. There are several parties involved, but OVHcloud is the only one to break silence about it.

It is easy to suspect that OVHcloud wants to curry favor as a European player, and distract customers from the unresolved fire issue. With no one talking about the fire, its stock market flotation in October went very well for the company.

But one small detail surfaced during the IPO. The fire is expected to cost the company something like €105 million, according to statutory filings. This figure could easily change, of course, given that the fire's cause and implications are still not determined. There are also unresolved claims from customers.

Class action

Some customers are not letting the issue go. Paris law firm Ziegler & Associates is running a class action lawsuit that claims that OVHcloud is shirking responsibility and should offer better compensation, to cover lost data and the business impact felt by customers. OVHcloud in response says the incident was beyond its control, and customers should have been aware that their servers were backed up in the same site, if at all.

A large part of OVHcloud's defense, when it fully delivers it, will rest on a detailed fire report - which we still don't have.

At the last count, 130 customers had signed for the action, in which Ziegler will specify damage requests from each one. This month, the law firm has once more delayed finally delivering its clients' claims to OVHcloud, because more OVHcloud customers are still coming on board.

What do we know?

At this stage, what do we actually know about the fire?

The fire broke out at 12.40 am on March 10. It took six hours for 100 firefighters to bring it under control, using 44 fire fighting vehicles. The French firefighters were helped by a Franco-German pump ship on the Rhine.

Before the fire, SBG2 was a five-story, 500 sq m data center. Afterwards, it was a ruin. Three other data centers on the same site were also impacted.

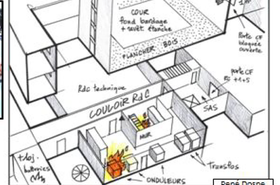

The design of data centers on the Strasbourg site had gone through several generations, starting with the shipping containers, and encompassing four data centers from SBG1 to SBG 4 by the day of the fire.

One year on, a fire fighters' report finally confirmed several facts about this fire. It appears to have started in a power supply room, where firefighters found UPS7 ablaze, with huge electrical arcs more than one meter long, preventing access.

In the days after the fire, Klaba had revealed that UPS7 had just had maintenance work the day before the fire broke out. On March 12, he said: "The supplier came and changed a lot of pieces inside UPS7, and they restarted it in the afternoon. It seemed that it was working, but in the morning we had the fire."

The firefighters say they could not deal with the power room fire immediately, because they could not turn the power off. It took them nearly three hours, until 03.28, to get power cut off to the site. During this time the electrical fire raged and flames spread through the data center.

That spread was apparently sped by the data center's wooden floors, which went up in flames. These floors were perhaps not as extreme a fire hazard as might be feared, as wooden building materials are designed to resist fire. But the delay in putting out the power room fire must have pushed them beyond their limits: the firefighters report that the power room ceiling was rated to resist fire for only one hour - and the lack of a cut-off switch left the power room burning for longer than that.

The firefighters observe that the data center had no automatic fire prevention or extinguishing system.

Finally, the firefighters describe the data center's two courtyards acting as a "chimney" that accelerated the blaze.

A few days later, on 20 March, firefighters had to return to deal with another fire in a UPS battery room on the site. Others noted that OVHcloud had been replacing UPS power cables at several of its sites.

The context

OVHcloud is refusing to respond to these details, claiming it still can't talk till we have a formal report (a more formal report than the firefighters' response).

This leaves us picking over observations from firefighters that are not data center experts, but which do connect with criticisms that have emerged during the year.

Starting with the lack of a power cut-off, it is true that data centers are designed to be difficult to switch off, so services keep running. For instance, DCD has been told that it is common practice not to provide an obvious cut-off switch for data centers, which might be tripped by mistake, bringing down services.

However, it's obviously dangerous and wrong to have no way of cutting the power at all. In this instance, several OVHcloud customers reported their services carried on well into the small hours with fire raging through the building.

During the year, an article in VO News by Clever Technologies claimed there were flaws in the power design of the site, for instance that the neighboring SBG4 facility was not independent, drawing power from the same circuit as SBG2. It's clear that the site had multiple generations, and among its work after the fire, OVHcloud reported digging a new power connection between the facilities.

Back in 2017, after an outage, OVHcloud (then known as OVH) promised to retire its container-based buildings and decommission them, and separate the facilities on the site into separate distinct power feeds. Reports in ZDnet.fr and elsewhere suggested that this work may never have been completed. It is claimed that some shipping container elements remained.

Other construction elements are being questioned. Early comments from firefighters said that the presence of wood and plastics made the fire worse. We know for sure that there were wooden floors, and the fire report confirms that they burnt.

The firefighters' mention of a "chimney" effect is also interesting. Before the fire, OVHcloud was very proud of its five-story design, in which natural convection provided air circulation to cool the servers. It's possible this sped the fire up.

Both Clever Technologies and ZDnet.fr claim that SBG2 had no automatic fire extinguishing system. OVHcloud's only response has been its promise a year ago, to set up a lab to investigate best practices in data center fire prevention.

But there are already plenty of established best practices for detection and prevention, including the use of inert gases to smother a fire without creating electrical short circuits. At some point, we will need to know whether OVHcloud was following them.

Time for answers

Beyond that, customers have issues with OVHcloud's service, saying the small print was not clear about whether data was backed up or not -- and where those backups were held. Some services were backed up to machines in the same building, so customers lost data when the building was destroyed.

It's clear that OVHcloud already knows the cause of this fire. It happened in an older facility that was built according to designs it no longer uses, and which was undergoing maintenance and upgrades.

We certainly hope and trust that OVHcloud is applying the lessons it has learned from the fire. It would be good if others could also learn.

It's unfair on customers and colleagues in the industry to keep these details private.