Data centers are engineered for high reliability, but all too often they go wrong, losing data and losing money for their customers.

The reasons aren’t hard to see. The facilities are complex systems depending on both technology and human activity, and will inevitably fail at some point. In most cases, the underlying root cause is human error, and increasing data center reliability is a matter of eliminating or reducing that wherever possible.

An upper limit of reliability

For systems like this, there’s a theoretical upper limit of reliability, which is about 200,000 hours of operation. This is because the human factor can be made smaller and smaller, but there is eventually a point when hardware will fail, whatever is done to improve the systems and procedures.

Well-established industries such as aviation are close to achieving the maximum possible reliability but, according to Ed Ansett of i3 Consulting, data centers fall short of it.

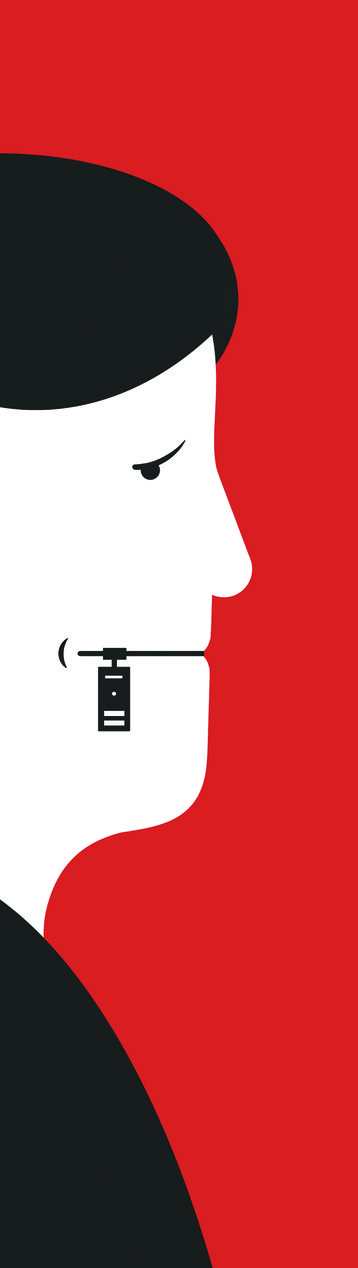

Why is this happening? According to Ansett, it’s down to secrecy. Failures repeat because they aren’t widely understood. Ansett presented his ideas in detail at the DCD Converged SE Asia event in Singapore last month.

Virtually all failures in complex systems are due to errors in the design, testing, maintenance or operation of the facility. Once a failure has occurred, it should be examined to understand and determine the root cause of the problems. Once the fundamental issues are identified, then it is possible to make changes to reduce the chances of the same failure happening again.

In the case of data centers, most root causes are down to human error – whether it is in the design phase, installation, maintenance or operation. Some potential faults are obvious, or at least easy to identify, such as generators failing to start, or leaks of water. But very often failures occur through a combination of two or three faults happening simultaneously, none of which would have caused an outage on its own.

In aviation, for example, these complex faults are often uncovered because, when a plane crashes, there is a full investigation of the cause of the accident, and the results are published. This is a mandatory requirement. When a data center fails, there is an investigation, but the results are kept secret, as the investigators sign a non-disclosure agreement (NDA).

Time for regulation?

Airlines share their fault reports because they are forced to by law. Aviation is a heavily regulated industry, because when a plane crashes, lives are lost. Data centers are different. There’s no obvious human injury when a data center crashes, and there are no central regulators for the industry. Any failure report would reveal technical and commercial details of a data center’s operation, which its owner would want to keep as trade secrets, hence the NDAs.

When faults in data centers are investigated (see box for some recent scenarios), the analysts come up with the root cause and suggest improvements to prevent the same thing happening again. But each time the fault crops up, few people can learn from it, because the information is restricted.

There’s no obvious human injury when a data center crashes, and there are no central regulators for the industry.

As a result, when investigators are called on to investigate a mystery fault, they often know instantly what has gone wrong – much to the shock of the data center operator.

At a recent fault investigation, Ansett only needed to know the basic details of the incident to make a guess at the root cause, which turned out to be completely accurate. It was a fault he had seen in several previous failures at data centers in other countries.

It was a failure that could have been predicted and prevented, but only if the results of previous failure investigations had been made public. Unfortunately, the information is not made widely available, which is a tragic waste of knowledge. It leaves operators designing and specifying data centers blindly: “Reliability is much worse than it need be, because we don’t share,” says Ansett.

It’s possible this may change in future, but the change might not be a pretty one. No industry welcomes regulation, and controls are normally forced on a sector in response to an overwhelming need, such as the desire to limit the loss of life in plane crashes.

Impact will increase

Data centers are becoming more central to all parts of society, including hospitals, and the Internet of Things, which is increasingly micro-managing things such as traffic systems, hospitals and the utility and systems delivering power and water.

As data centers are integrated into the life-support systems of society, their failure will become more critical.

“Over the course of the next few years, as society becomes more technology-dependent, it is entirely possible that failures will start to kill people,” Ansett warns. At this point, the pressure will increase for data centers to be regulated.

The only way to avoid this sort of compulsory regulation would be for the industry to regulate itself better and take steps to improve reliability before there are serious consequences of a fault.

There are some precedents within the technology industries. For instance, IT security issues and best practices are already shared voluntarily via the world’s CERTs (computer emergency response teams).

In the data center world, the Uptime Institute certifies data centers for the reliability of their physical plant in its Tier system, and is also looking at the human factors in its M&O Stamp.

But the industry is still groping towards a solution to the tricky problem of how to deal with the root causes of failure.

This article appeared in the October 2015 issue of DatacenterDynamics magazine