The world's leaders are set to deliver an inadequate response to the climate emergency in the COP26 event in Glasgow this week.

The science has given us a clear warning. The "Code Red" warning from the UN's Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change spelled out what we need to do. We know the data. We know how much greenhouse gases (GHBs) we can afford to put into the atmosphere and keep below the target temperature rise of 1.5°C. We know the consequences of going above that figure. We are already at 1.2°C above pre-industrial levels, and we can see the consequences all around us. There are wildfires in the Arctic.

The COP26 conference knew what it had to do. The world's nations had to agree to cuts in their carbon emissions, known as “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs), which would add up to enough to keep us within the 1.5°C budget. They also had to deliver on a package of finance that would enable the poorer nations to move to low carbon technologies, and also to survive the worst effects of global warming. The required NDCs were known in advance, and the nations had set a budget of $100 billion per year for poorer nations, back in the Paris agreement of 2015.

On both counts, they are going to fail. The NDCs don't add up, and some countries have gone backwards. The finance package agreed in 2015 is still not delivered, so the world is going to head forward without the level of international trust we need.

Despite knowing the dire consequences, and the minimal level of action required, the draft agreements which are circulating are an admission of defeat, and a promise to try again next year. And if that wasn't bad enough, the final hours of the conference will be all about how many loopholes powerful lobbyists can insert into the final wording, to enable oil producers and coal-based economies to dodge the necessity of simply stopping.

There's an optimistic narrative that points to the smaller achievements the meeting has made, like a promise to end deforestation and reduce methane emissions. But these are all too little and too late - and they don't compensate for the underlying global failure.

Promises, promises

Against that backdrop, how is the tech industry faring? It's certainly talking a good game. COP26 has seen a gamut of optimistic announcements from tech firms large and small. But to my mind, that optimism is misplaced. Like world governments, tech firms are ignoring the consequences of their actions, looking for loopholes to continue doing what they do, and if all else fails, simply saying they can't help it and passing the blame on to others.

Take Amazon Web Services. At the start of the conference, the company proudly announced that utility ScottishPower had opened a 50MW wind farm, entirely funded by Amazon, without any government support. Since that farm is generating energy to be used by AWS, why on earth would it receive any government support? Amazon doesn't even pay its fair share of taxes, so the UK government shouldn't be subsidizing its power.

But there's more. We all know that wind is intermittent, and that farm will only produce energy on windy days. AWS's data centers, on the other hand, will want power continuously 24x7. So, far from helping green the UK's grid, this deal will actually accentuate the peaks of generation, and increase the mismatch between demand and consumption. This deal hands the UK's grid a problem. Thanks a billion, Jeff!

A bunch of providers have promised to be net-zero, but many of these promises come with extended dates, when there's a requirement to act now. Others are somewhat unfeasible. For instance, earlier this year, SUNeEvision's CEO Raymond Tong told me his company has a massive growth program underway in Hong Kong. The grid there is very carbon-intensive and, under China's slow decarbonization plan, will remain that way for very many years. In those circumstances, data centers directly contribute to global warming, and building them will harm the planet.

Other announcements included a paper sponsored by Microsoft, which outlined how data centers (and other buildings) could massively reduce their carbon footprint with novel materials such as mushroom-based tubes, and earth-slab floors. That's an interesting take. It turns out that the emissions from building materials in a data center can be more than those from the IT equipment it holds, so it's a good idea.

The trouble is, these novel materials are proposals and only point up the fact that most data centers are currently built in the quickest way possible with no concern for emissions.

A panel on climate change at DCD>Connect London, our first face-to-face event in two years, heard a lot of good news, including Europe's Climate Neutral Data Center Pact, in which the region's providers have promised to be carbon neutral by 2030. But it also contained some candid admissions.

Panelists from tech firms with the industry's best green credentials admitted that the facilities they are building today will certainly still be in use in 2030, and they don't match their climate-neutral aspirations. No one has replaced any concrete with zero-carbon materials in data centers yet, that I know of (though the use of CarbonCure concrete does mitigate a little of the output).

One speaker admitted the following: "I believe that the data centers we are building today, most of them are not anywhere near where we're gonna need to be in 2030. In Europe, we're moving east. There's more going on in Eastern Europe, and they're big coal-producing countries that we're putting data centers in."

Chillingly, he explained why this is happening: "It's the market, we're following the market. The demand is there. So we have to build there. Otherwise, that would be bad on our shareholders."

Whatever they tell the world, it seems clear that tech executives feel more responsibility to their shareholders than their children.

Still, that's capitalism, and apparently we can't do anything about it. That same criticism can be leveled at countries with agreements on levels of development like Norway. Their promise to support greener facilities is coupled with an aspiration - to build many more of them. The net result of that is still an increase in the tech footprint.

Optimism: the tech "handprint"

How big is this footprint? In 2015, Anders Andrae, a researcher in energy efficiency and sustainability with Huawei in Stockholm published a paper that predicted that data center electricity use is likely to increase 15-fold by 2030, to eight percent of global demand. That's his more optimistic figure: he also includes scenarios where it could go as high as 20 percent.

That paper got less traction in the tech industry than a brighter take from Arman Shehabi and Jonathan Koomey (and others) at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratories (LBNL), that came out one year later. Shehabi and his colleagues pointed out that data center energy use in the US (for colocation data centers where statistics were available) had remained relatively constant while the amount of compute power had multipled many times. This was due to increasing power efficiency due to Moore's law, virtualization, and the Cloud.

That's a message which the industry has taken to hear. We've jumped to the belief that tech fixed the tech crisis. That's been used as a marketing message during COP26 by (again) Amazon. In a paper sponsored by Amazon, 451 Research found that AWS data centers were five times more efficient than the European average. All EU businesses have to do to move to the cloud is to "Move to AWS," the company concludes.

Sadly, AWS is flogging a dated Utopian idea of a move to the cloud. For multiple reasons, the early adopters of cloud have become disillusioned and are moving back to a new model of colocation, which has to combine on-site IT with on-ramps to the cloud, and can't avail themselves of the dream of full cloud adoption.

But is there a genuinely optimistic view to take on the contribution of technology?

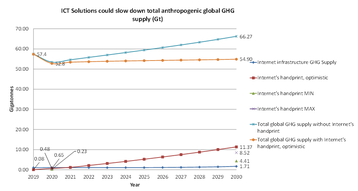

Let's go back to Andrae. This year he published a paper that pointed out that as well as a "footprint", the Internet has what he calls a "handprint" - a beneficial, effect on other sectors of the world.

Instead of flying, people can attend meetings by Zoom. Timely information can make smart cities run more efficiently, and e-books use less resources than printed paperbacks.

Now, I've heard this effect quoted endlessly, and rather vaguely, as a conversation-stopper. "Data centers are the solution, not the problem," I'm told. But there never seems to be any attempt to measure the beneficial effect of the surge in data, and compare it with the footprint.

When I hear about the massive energy required for AI and HPC systems - now in kW per rack units - I wonder about the benefits it provides. How much of it is for creepy behavior tracking? How much is wasted in cryptocurrency speculation? And if I adopt some useful AI, say putting my home heating under smart AI control, how much energy does an AI system have to spend, to shave a kWh off of my heat usage?

I've always been skeptical about the relative benefit these applications can provide compared to their footprint, but Andrae has made some approximations, done the math, and come up with a positive answer.

"All in all, Internet’s handprint will be 11.37 Gt in 2030," he says in his March 2021 paper "...safely higher than the Internet's footprint." He admits there's some optimism there, but still thinks the Internet cuts four to seven times as many Gigatonnes of GHG as it produces.

Faced with humanity's proven ability for unfounded optimism, I'll reserve judgment. But maybe we need some good news right now, so let's at least welcome the idea.