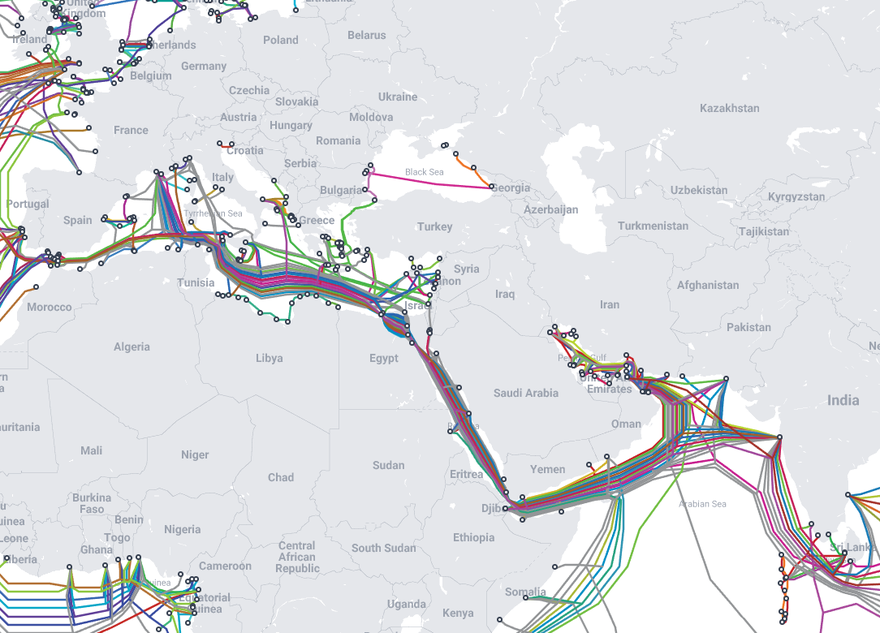

Today more than a dozen cables pass through the Red Sea. TeleGeography estimates that more than 90 percent of all Europe-Asia capacity is carried by cables through this channel. The firm estimates for the likes of India, Kenya, and the UAE, more than 40 percent of each country’s interregional bandwidth is connected to Europe via Red Sea cables.

The Red Sea has two natural bottlenecks; the Egypt and the Suez Canal in the north, and the Bab al-Mandab Strait in the south. For years, the focus has been on how to diversify the northern part.

Alternative fiber routes connecting the Med and North Africa to Asia and sub-Saharan Africa have long been eyed by the industry. But the focus has long been on bypassing the Suez Canal and avoiding the tithes placed on cables by Egypt. Work has been ongoing to connect the Med to the Red Sea via Israel instead.

“When you want to connect India or Southeast Asia to Europe, the most natural ways is through the Red Sea,” says Bertrand Clesca, partner at subsea cable consulting firm Pioneer Consulting. “But today, you have people thinking about new solutions.”

Egypt’s stranglehold on cables connecting Europe to Asia and West Africa is a by-product of British colonialism. The Suez Canal was created to make shipping easier and also offered a new route to connect the empire, first by telegraph cable, and later – via a now independent Egypt and state-owned telco Telecom Egypt – fiber cables.

With the recent Houthi attacks on shipping lanes at the southern end of the Red Sea presenting new risks to cables and cable ships in the area, there’s renewed interest to find fiber routes that not only bypass Egypt but eschew the Red Sea altogether.

“Previously, the main driver [for new cable routes] was to avoid crossing Egypt, because Egypt Telecom has kind of monopoly,” he adds. “People have been looking for years to find a way to avoid this. And now because of what we have in Yemen, people are looking to avoid the Red Sea [entirely].”

Houthis and the Red Sea

The Red Sea spans around 2,250km (1,400 miles), running from the Suez Canal in the north to the Bab al-Mandab Strait in the south, before meeting the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean. Also known as the Gate of Grief or the Gate of Tears, the 26km (14-mile) strait runs between Yemen on the Arabian Peninsula and Djibouti and Eritrea in the Horn of Africa, connecting to the Gulf of Aden (and onto the Indian Ocean).

Like the Suez, the straight is a major bottleneck for the region, with around 15 cables currently passing by Yemeni waters. More cables including the Blue-Raman, India-Europe-Xpress, and 2Africa systems are due online in the coming years, all inevitably passing through the strait. Many have seen delays in deployment due to challenges around Yemen.

While this has traditionally not been a major concern for cable operators, recent incidents are presenting a new challenge.

Pro-Israeli think tanks have suggested the Houthis – an Islamist political and military organization designated a terrorist group by the US – may have made threats against subsea cables in the region.

While the group – which controls large swaths of Yemen, including a significant stretch of the country's coastline – has denied this, the group is attacking shipping lanes in the region, which has indirectly resulted in cable damage.

In February the M/V Rubymar was struck by an anti-ship ballistic missile fired by the Houthis. The ship’s crew left the ship anchored but slowly taking on water. It began drifting and its anchor is thought to have damaged the AAE-1, Seacom/TGN, and Europe India Gateway (EIG) cables.

The Houthi-controlled government has said it would grant safe passage for ships granted permits to fix the cables, but at the time of writing, no announcements have been made around efforts to fix the cables due to the risks associated with sending cable ships into dangerous waters.

Spurring new interest?

With the current situation around Yemen unlikely to be resolved any time soon, interest in alternative cable routes that avoid the Red Sea altogether is growing.

Google’s Blue-Raman cable was set to connect Europe to Asia via Israel; running south over land to Jordan and rejoining the Red Sea via the Gulf of Aqaba and avoiding the Suez. The planned Andromeda cable from Grid Telecom and Tamares Telecom would follow a similar terrestrial route, but also land at Haql, Saudi Arabia.

While it may bypass Egypt, that route, however, does nothing to avoid Yemeni waters further south.

Instead, Alan Mauldin, research director at TeleGeography, tells DCD that there are several efforts to try to link across the Arabian Peninsula.

“There's always been lots of different ideas proposed,” he says. “Building a cable through Jordan, Syria to Turkey. But then the Syrian war happened. And you can’t really go around Egypt via Sudan or Libya.”

“If you could go from the UAE or Oman across Saudi out through Jeddah perhaps that would be a bypass effectively,” he adds. “There’s already terrestrial network infrastructure throughout all those countries. But I think it's a commercial issue and it's a geopolitical issue as well.”

Israel as the new hub

While Mauldin says it's unclear if the Arabian Peninsula could emerge as a main way to route traffic, he knows it is “being discussed” as an option.

Any route through the peninsula would likely pass through Israel, and a number of new European cables are landing in Israel.

2023 saw Tamares Telecom and Grid Telecom announce the Andromeda cable that will connect Israel, Cyprus, and Greece.

At least one company is confirmed as planning a Eurasian fiber route that connects Israel to its Middle Eastern neighbor. First announced in 2020, Cinturion, a fiber network solutions provider, is currently building its TEAS – Trans Europe Asia System – a multi-cable system running between Europe and India, with funding from US investment firm Stonecourt Capital.

In Europe, the system will comprise a pair of submarine cables – Med West (MW) and Med East (ME) – running from Marseilles, France, and Bari, Italy to the Eastern Mediterranean coast. From there, one route will run through the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Oman, while the southern route will pass through the Red Sea, both finally landing in Mumbai, India.

The north branch will land at Ras Al Khair in Saidi, Abu Dhabi in the UAE, and Barka in Oman. Landing points for the south branch of TEAS include Duba and Thuwal in Saudi, Djibouti City in Djibouti, and Salalah in Oman. Both cables would run through Israel – the north route through the Rishon area of Tel-Aviv, and the southern portion through Ashkelon.

Pioneer’s Clesca says there are other projects similar to TEAS in the works that aren't public yet.

Using Israel as a new major interconnection point for the Middle East wouldn’t come without challenges. The county is amidst major internal conflict with Gaza at the time of writing, and relations with its immediate neighbors can make the politics of new cable routes difficult.

In 2022, Saudi Arabia signed a strategic partnership with Greece to build a submarine Internet cable linking the two nations. Specifics of the cable route were not shared, but Saudi Arabia does not border the Mediterranean Sea, so a cable would have to cross Israel or Egypt.

After speaking to developers and operators in the Middle East, Pioneer’s Clesca suggests the mindset amongst many operators in the region was that while it's not a good situation right now, it will not change long-term plans to develop Israel as a hub in the region. There was also a view that the situation in Israel may stabilize sooner than in Yemen.

“Subsea cable systems are almost always interconnecting different countries, different regions, so by definition are geo geopolitical animals,” says Clesca. “It is driven by the risk appetite of the cable developer, but in this industry, people are risk-averse.”

“I'm not an expert in geopolitics, but what I can say from the subsea cable industry, my perception is that discussions are still ongoing in Israel,” he adds. “For the mid-term, there is no change of plan with using Israel as a new hub to connect the Mediterranean and the Middle East.

Turkey could also be a new option. Iraq's Informatics and Telecommunications Public Company (ITPC) and Kuwaiti telco Zajil Telecom recently signed an agreement to create a communications route from the Gulf region to Europe. The route will create a telecommunications corridor to Europe, via Iraq, and will pass through Turkey.

Currently, Turkey lands two cables connecting Europe to Asia via the Red Sea: SeaMeWe-3 and -5. It also lands the European MedNautilus system. However, 2024 saw Telecom Italia subsidiary Sparkle announce plans for GreenMed, a new cable connecting Italy to Turkey via Greece, Croatia, Montenegro, and Albania.

Sunil Tagare, founder of Flag Telecom and a cable that runs through the Red Sea, recently said on LinkedIn a long-term solution to this Red Sea issue was to build a 100-1,000-fiber pair terrestrial cable loop connecting Oman, UAE, and Saudi Arabia and extend it to the Mediterranean Sea.

In the meantime, while it was being built, however, he suggested paying the Houthis a ransom of $1 million per working cable per month not to break the cables and to enable cable ships can resume their cable maintenance and installation activities – though he agreed it was “not a good solution.”

Africa rising beyond Egypt?

Many of the suggested routes traverse the Middle East, but Africa could present a potential solution beyond the existing Egyptian routes.

Djibouti is already a major landing point for cables in the area. A terrestrial cable linking the country to Egypt’s neighbor Libya – which is set to see the BlueMed and Medusa cables land in the near future – via Sudan could offer an alternative route to the Med and Europe. Libya’s western neighbor Tunisia is also set to see more European cables – Peace and Medusa – land in the country.

Going around South Africa may be too far, but Bertrand Clesca, partner at subsea consulting firm Pioneer Consulting, suggests a terrestrial fiber route bisecting sub-Saharan Africa’s middle could be an alternative route for Asian companies wanting to reach the Atlantic; a cable from east Africa to west could offer a relatively low-latency route onwards to the eastern side of the Americas, or north to Europe.

“It’s not ready yet today, but we are seeing people in Africa develop trans-African coast-to-coast routes connecting, for instance, Kenya or Tanzania to DRC or to Cameroon,” he says.

“It could be a way for cable systems coming from India or Asia to traverse Africa and after that to go up along the west coast of Africa to connect to Europe or to the US. We are seeing more and more projects like that.”

While not at the same level as many other regions, fiber network capacity across the continent is growing. MTN Group subsidiary Bayobab is planning the East2West cable project; a terrestrial cable connecting eastern Africa to the continent’s west. The partnership – which includes investment firm Africa50 – will invest up to $320 million in connecting ten African countries for a 2025 completion date.

He also noted more terrestrial routes going from Djibouti on the side to the west side of Africa are being developed. The idea, Clesca suggests, is to avoid difficult points, to add diversity, and to reduce latency.

“For instance, if China wanted to connect to Latin America so they can do both ways (east via the Pacific and west via the Atlantic), it could be beneficial to land in Kenya to go west across Kenya, Tanzania DRC, and after that to find another cable system to go to Brazil,” he says.

Such a route would be shorter compared to today, which connects to Egypt, then Europe, onto the US, and down to Brazil; or from Europe to Brazil via a cable such as EllaLink if firms wanted to avoid the US.

Doug Madory, director of Internet analysis at Kentik Inc., is still dubious if such a project would see traction.

“There’s more connections crossing these countries,” he says. “But going through some of these places... there are some unstable countries that to run lines through, it exposes risks.

No easy solution

It’s hard to tell if any of the proposed projects will ever usurp the Red Sea’s dominance in the global topology of the world’s subsea cables.

Plans for cables bypassing the region have come and gone. Many have tried, and few succeeded in creating commercially viable alternatives. High costs, tricky international relations of routes, and regular ongoing conflicts have all created challenging obstacles over the years.

“I think it certainly provokes people's interests, going terrestrially,” says Kentik’s Madory. “But it's tricky to really avoid the Red Sea. We're just kind of locked into this geography to some extent.”

“We've been in this place for a long time and there's been a lot of attempts, a lot of projects, and they just never really materialized. And then we end up going back to just running everything to the Red Sea again.”

In 2010, Saudi Telecom Company teamed up with Jordan Telecom Group (JTG), Turk Telekom, and Syria Telecom for an ambitious terrestrial cable spanning some 2,530km (1,570mi). JADI - named so because it would link Jeddah, Amman, Damascus, and Istanbul. The cable has reportedly been damaged due to fighting in Syria and never repaired.

Announced in 2011, the EPEG cable set off from Oman, briefly crossing the Gulf of Oman and into Iran. From there, it traveled north, up through Azerbaijan, and into Russia, where it veered west via Ukraine, Hungary, and Austria, before terminating in Frankfurt, Germany. While it found at least one customer in Bahrain, Batelco, the cable struggled to attract customers and may have been damaged during Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

In 2020, the CEO of Israeli telecoms company Cellcom, Avi Gabbay, said that it hoped to build a terrestrial fiber cable from Israel to Dubai. It then hopes to launch a submarine cable from Israel over to the EU. However, no other details about the project were made public and Gabbay was fired by shareholders in 2021 for being too independent. The company did not respond to DCD’s previous requests for comment.

“You get these economies of scale by everybody going the same route because you’re dividing the cost of that route,” says Madory. “These long-range terrestrial projects end up often being harder than they seem, and we don’t often see these terrestrial efforts make a difference.”