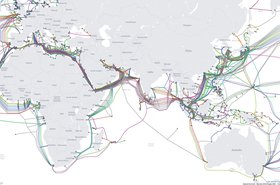

The Red Sea is a major artery of the global Internet. More than a dozen subsea cables pass through it connecting Europe to the Middle East, Africa, and APAC, transporting huge swathes of data traffic.

But this choke point presents a risk. For years, the industry has been looking for an alternative way to reach the Indian Ocean from the Mediterranean Sea, but mostly to avoid Egypt and the pricey cost-of-entry requirements to run cables alongside the Suez Canal.

This feature appeared on the cover of the latest issue of the DCD Magazine. Read it for free today.

However, at the other end of the Red Sea, a more urgent and violent risk is now causing issues for global connectivity.

Rebel groups actively attacking ships in the Red Sea have indirectly damaged a number of cables after a listing vessel dragged its anchor.

Others have accused the groups of making direct threats against cables in the area. But how real is the threat?

Yemen, subsea cables, and the Houthis

The Red Sea spans around 2,250km (1,400 miles), running from the Suez Canal in the north to the Bab al-Mandab Strait in the south, before meeting the Arabian Sea and Indian Ocean.

TeleGeography estimates that more than 90 percent of all Europe-Asia capacity is carried by cables through this channel. The firm estimates for the likes of India, Kenya, and the UAE, more than 40 percent of each country’s interregional bandwidth is connected to Europe via Red Sea cables.

Also known as the Gate of Grief or the Gate of Tears, the 26km (14-mile) strait runs between Yemen on the Arabian Peninsula and Djibouti and Eritrea in the Horn of Africa, connecting to the Gulf of Aden (and onto the Indian Ocean).

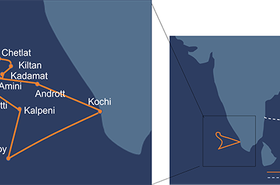

Despite only being the landing point for four cables, around 15 cables currently pass by Yemeni waters. More cables including the Blue-Raman, India-Europe-Xpress, and 2Africa systems are due online in the coming years, all inevitably passing through the strait.

The Bab al-Mandab is a natural bottleneck between the Middle East and the coast of Africa, meaning any subsea cables connecting Europe to Asia are almost certain to pass close to Yemeni waters (and, by extension, Houthi-controlled areas).

On the other side of the strait lies Eritrea, an isolationist country described as the ‘North Korea of Africa,’ with no subsea cables and little Internet freedom. Bertrand Clesca, partner at subsea consulting firm Pioneer Consulting, tells DCD most cable operators have generally laid cables in Yemeni waters as the country was historically easier to deal with than Eritrea.

The Houthi cable threat – real or imagined?

Like cell towers and data centers, subsea cables are critical infrastructure, providing connectivity to the outside world. This has long been known and exploited during times of conflict; one of the first such moves was made by the British during World War One and saw them cut Germany's undersea telegraph cables. Another cable connecting Manila to mainland Asia was cut in 1898, during the Spanish-American War.

Intentional threats of violence against cables are often perceived through the lens of nation-states in deep waters. A 2017 Policy Exchange report produced by UK Prime Minister Rishi Sunak – then merely an MP – warned of ‘aggressive Russian submarines in the Atlantic’ and the need for more international treaties. Few, if any reports, have ever really considered threats to subsea cables from terrorist groups, given their relative obscurity and the difficulty in reaching the seafloor.

However, that changed in late 2023. The Middle East Media Research Institute (MEMRI) – a think tank founded by a former Israeli Intelligence officer and a political scientist described as a ‘neoconservative and revisionist Zionist’ on Wikipedia – said Telegram channels reportedly affiliated with the Houthis had made implied threats against subsea cables in the Red Sea.

"There are maps of international cables connecting all regions of the world through the sea. It seems that Yemen is in a strategic location, as Internet lines that connect entire continents – not only countries – pass near it,” one Telegram post said, accompanying a map of cables in the region.

This news was later picked up in mainstream media worldwide after Emily Milliken, SVP and lead analyst at US-based defense intelligence consulting firm Askari Defense & Intelligence, wrote a blog highlighting the MEMRI research, the criticality of the Red Sea in telecoms, and some of the Houthi military capabilities.

“They didn't directly threaten the subsea cables,” Milliken tells DCD. “But they alluded to the fact that they were so important in the area. Which, for an organization that has been launching maritime attacks, is obviously a concerning statement.”

Government ministries and telecoms firms backed by the UN-recognized government condemned the reported threats to the region’s cable infrastructure, while Houthi-backed agencies said the reports were untrue.

The General Corporation for Telecommunications and the Yemeni International Telecommunications Company (TeleYemen), in Aden [i.e. the UN-backed government], said it “strongly condemned” the threats of the Houthis to target international marine cables.

The Ministry of Communications and Information Technology (MTIT) in Sanaa [i.e. the Houthi-controlled ministry] denied there was any danger to subsea cables in the regions.

In a comment made through the Internet Society, the MTIT said reports of threats were “fabricated lies” being told to “cover the crimes committed by the Zionist entity in the Gaza Strip.”

“The approach of the Government of Yemen, through the MTIT, is to focus on building and developing the telecom and Internet services, and expanding the range of services through the licensed telecom institutions and companies,” the MTIT added in a separate statement.

Abdul-Malik al-Houthi, leader of the Houthi movement, went so far as publishing a video saying the group has “no intention” of targeting submarine Internet cables in the region.

While she acknowledges it might not be in their best long-term interest, Milliken says she views the threats to cables as “credible” and is “dismissive” of Houthi claims to the contrary, given previous promises to only target Israeli-related shipping.

“They're trying to show themselves as a bigger threat in the region in order to garner more support and show themselves as an active part of Iran’s resistance groups,” she says.

But there may be a kernel of truth in Houthi claims to want to keep data flowing in the region, though for purely monetary reasons.

The Counter Extremism Project (CEP), a not-for-profit policy organization aiming to ‘combat extremist ideologies,’ has said the Houthis have been using its control of large swathes of Yemen’s telecoms infrastructure – including operator Yemen Mobile – to monitor and censor its populace while profiting from a growing Internet user base.

The group has reportedly repeatedly raised prices while failing to invest in the country’s infrastructure. In 2022, the United Nations described the telecommunications industry in Yemen as “a major source of revenue” for the Houthis – CEP estimates potentially tens of millions of dollars.

Intentional damage against digital infrastructure by groups isn’t new. Cell towers are often the target of conspiracy theorists, and terrestrial fiber cables have previously been purposefully cut. But this is the first time a terrorist group has been said to be a threat to subsea infrastructure – and motive remains a question if the Houthis really were interested in attacking cables.

Israel is largely dependent on terrestrial cables and subsea cables landing on its Mediterranean coastline, so any cuts in the Red Sea would have minimal impact on the country the Houthis have said they want to inflict the most damage on.

“They wouldn't really hurt the Western countries that they are targeting; it's not going to really affect Israel or Great Britain, certainly not the United States,” says Doug Madory, director of Internet analysis at Internet monitoring firm Kentik Inc. “It's mostly countries either to the south or to the east that are affected by the loss of connectivity including Iran, which is their primary backer.”

However, cable damage in the Red Sea could impact Yemen’s Saudi neighbors, which could be a boon for the Houthis and Iranians.

“It's essential to consider all possibilities,” Ahmed Nagi, senior analyst for Yemen at the non-profit think tank Crisis Group, tells DCD. “The Houthis might indeed pose a threat to subsea cables, especially if tensions in the maritime lanes escalate further.”

One Red Sea cable – the Global Cloud Xchange-owned Falcon system – lands in Iran as well as Saudi and Yemen, so attacking it could impact the Houthis and their only ally. But damaging the Saudi enemy could still appeal.

“The Houthis are not a wholly owned subsidiary of Iran,” Milliken says. “It doesn’t necessarily matter if something is in Iran’s best interest. They are more than happy to do attacks that don't necessarily benefit Iran and in some cases are detrimental.”

Are cables really under threat?

Did the Houthis really make a veiled threat at the cables? It’s hard to say. MEMRI no doubt has a pro-Israeli slant that might influence their assessment of the posts. But it’s a fact they are attacking ships of all stripes in the Red Sea and that is impacting cables indirectly.

The Houthis – officially known as Ansar Allah – have been attacking commercial ships passing by Yemeni water since November 2023. Dozens of ships have been attacked by drones, missiles, and speedboats. The Houthis claim to only be targeting Israel-linked vessels in support of Palestinians in Gaza amid the ongoing invasion by Israel.

US Central Command condemned what it calls the “reckless and indiscriminate attacks” on civilian cargo ships by the Houthis. The US State Department has labeled the Houthis as a ‘Specially Designated Global Terrorist group’– meaning they have committed or pose a significant risk of committing acts of terrorism – ranking them alongside Al-Qaeda, ISIS, Hamas, and Hezbollah.

At the time of writing, the Israel-Gaza conflict continues and Houthis continue to target ships in the Red Sea.

But could the Houthis directly attack subsea cables in the Red Sea if they wanted to? Some military experts have said the Houthis may have the ability, but others still have doubts.

“I can’t see any part of the Houthi arsenal actually being dangerous for the subsea cables,” Bruce Jones, senior fellow at the Brookings Institution, told Foreign Policy. “The question becomes, do the Iranians have the capability, and would the Iranians take that step?”

"I assess it's a bluff, unless it's an attack on a terminal," former Royal Navy submarine commander Rear Adm John Gower told the BBC. "It would need an ally with the capability [of] a submersible plus the ability to locate [the cables].”

"There is nothing I've seen in the Iranian orbat (Order of Battle) that could touch these cables, certainly not their submarines," added former Royal Navy Cdr Tom Sharpe. "Diving is an option but it's deep and busy so I think it would be pushing it.”

However, Wilson Jones, defense analyst at GlobalData, told AirForce Technology: “Yemen is near a disproportionate number of international undersea Internet cables. It would be very difficult to stop the Houthis if they made a determined effort to target these cables.”

Carolina Pinto, thematic analyst at GlobalData, added that while they likely do not have the technological capabilities to reach cables that are hundreds, if not thousands, of meters underwater, they could “maybe target one or two of the shallowest cables.”

While it reaches a maximum depth of 3,040m (9,970ft) in the central Suakin Trough, the Red Sea averages a depth of around 490 m (1,610ft). At its shallowest, however, some points are at depths of as little as 100m (330 ft).

While the Houthis might not have submarines, undersea robots, or the ability to hit the deepest parts of the Red Sea, it’s possible to inflict damage on subsea cables without the backing of a major navy.

In March 2013, three divers were arrested by the Egyptian Navy off the coast of Alexandria after cutting the SeaMeWe-4 cable by detonating underwater explosives. Internet speeds reportedly fell around 60 percent after the incident. A motive wasn’t revealed and it’s unclear if they were charged and/or sentenced for the damage.

In 2007, it was reported that police had seized more than 500km of telecom cable taken by fishing vessels to sell for scrap – including an 11km segment identified as belonging to the SeaMeWe-3 cable.

Askari’s Milliken points out that the Houthis are backed by Iran, which has provided a large amount of arms and equipment to build weapons, including maritime-focused equipment. They have been known to use waterborne explosive devices, and the Combating Terrorism Center, an academic institution at the US Military Academy, suggests the Houthis have previously undertaken combat diver training on Zuqur and Bawardi islands in the Red Sea.

Regardless of their interest and ability to directly attack cables, their very real and direct attacks on boats are having an impact on future cables set to be laid in the Red Sea.

TeleGeography noted in a recent blog that a segment of the 2Africa cable set to lie in Yemeni waters is yet to be laid.

Multiple industry sources named the likes of Blue-Raman, Africa-1, and SeaMeWe-6 as other upcoming cables that are likely to be delayed in the Red Sea because of the situation.

Direct threat or collateral damage?

Regardless of whether the Houthis have the motivation or capabilities to directly attack a cable, their attacks on the region’s shipping industry have indirectly achieved the same end result.

February 18 saw the M/V Rubymar struck by an anti-ship ballistic missile. While one missile missed, the missile that did hit caused the crew to evacuate to a coalition warship and nearby merchant vessel. The drifting and listing Rubymar, however, is thought to have caused significant damage to a number of cables in the region.

The Rubymar crew left the ship anchored but slowly taking on water. It began drifting and it’s thought that the ship is to blame for damage caused to three cables in the area.

The AAE-1, Seacom/TGN, and Europe India Gateway (EIG) cables were all said to have been impacted around the same time in the area where the ship was drifting.

Seacom was initially the only company to publicly confirm cable issues, but Tata later also acknowledged an impact. Early reports – especially those in Israel – were quick to say the cables had been deliberately damaged by the Houthis, with the Rubymar details only coming out later.

DCD’s sources say damage to the other cables has also been confirmed – and though the Rubymar theory hasn’t been completely confirmed, at the time of writing it is the industry’s best guess consensus as to the cause of the damage.

In a sector where accidental damage to cables by fishing boats and anchors is common, this is likely the first time a cable has been damaged as a by-product of attacks on ships.

The MTIT – controlled by the Houthi administration in Sana'a – denied any involvement in any cable damage.

"MTIT and Government of Yemen reaffirm its obligation to the general position of the Yemen Republic toward the submarine cables [and] keen to keep all telecom submarine cables and its relevant services away from any possible risks," the ministry said.

Yemen’s Transportation Ministry, currently under Houthi control, said the “hostilities on Yemen by the British and US naval military units” actually caused the disruption, which “jeopardized the security and safety of international communications and the normal flow of information.”

The MTIT said it was "keen" to facilitate the repair of any submarine cables in the region, so long as parties obtain the required licenses and permits from the Sana'a Maritime Affairs Authority.

"The Sana'a MTIT and GoY also brings to notice that Yemen's decision to ban the passage of Israeli ships does not pertain [to] the other international ships which have been licensed to execute submarine works within the Yemeni territorial waters," the ministry said.

The Rubymar, a Belize-flagged, UK-owned bulk carrier, sank on March 2 at approximately 2:15 a.m. (Sana'a time), according to a US CENTCOM update. It was carrying approximately 21,000 metric tons of ammonium phosphate sulfate fertilizer at the time, which presented an immediate environmental risk to the area.

Ahmed Awad bin Mubarak, the foreign minister of Yemen's internationally-recognized government in Aden, said in a post on X (formerly Twitter): "The sinking of the Rubymar is an environmental catastrophe that Yemen and the region have never experienced before. It is a new tragedy for our country and our people. Every day we pay the price for the adventures of the Houthi militia.”

No easy fix

The situation may get worse before it gets better. The cable damage has been felt across Africa and Asia, and at time of writing, no repairs have been made.

“It doesn't matter what caused it, right now what matters is how fast can we repair the cables,” says Alan Mauldin, research director at TeleGeography. “That's what the focus should be; how challenging is it going to be to get the permits? Can you get insurance? And as a maintenance company; do even you want to send your crew and vessel into an area where there could be active military activity happening?”

The Red Sea still has a number of undamaged cables serving Asia and the east coast of Africa. Normally cable operators have maintenance contracts with cable ship companies to ensure cable breaks are dealt with quickly, but in an active conflict area, the picture is more complicated.

Some industry experts have suggested the current conflict situation may trigger some force majeure clauses in the contracts, but DCD has been unable to confirm this. The Houthi-controlled MTIT may have promised safe passage to cable ship operators with the right permits, but that may be of little reassurance to those aboard when the group has previously kidnapped UN and Red Cross staff.

“I don't know that anybody wants to bet their life on, whether the Houthis correctly or incorrectly ascribe your ship to being a part of their enemy or not,” says Kentik’s Madory.

Even for cable ship companies willing to put their crews at risk, bureaucracy might be more of a stumbling block. It will be difficult to find insurance that covers sending ships into dangerous waters, and there are likely legal ramifications of doing business dealings with sanctioned organizations linked to terrorist groups to try and secure permits.

For now, there is enough spare capacity on the remaining cables and alternative routes – combined with backup satellite capacity – to mitigate much of the damage.

Intelsat has said its satellites are providing backup connectivity for a number of customers that were sending data via subsea cable before the incident. The operators of SeaMeWe-5 have said demand on its cable has gone up since the break, while SeaMeWe-4 recently benefited from an upgrade that doubled its capacity from 65Tbps to 122Tbps.

Hong Kong’s HGC said that while the cable breaks had “limited” impact in Hong Kong, the company had “devised a comprehensive diversity plan to reroute affected traffic.”

“Having a few faults is a normal thing to plan and accommodate for, it happens,” says TeleGeography’s Mauldin. “But if you have a higher number of breaks on higher capacity cables, there'll be a point where it will start having a major impact on connectivity [in the region].”

Mauldin says we’re “not close to that point yet," but a suspected undersea landslide that damaged several cables off the coast of Côte d'Ivoire a few weeks after the Rubymar incident has added to the continent’s capacity crunch and is unlikely to help matters. Repairs off the Ivory Coast have begun.

Repairs in the Red Sea are possible, though. In November, Global Cloud Xchange was able to complete scheduled maintenance on the company’s Falcon cable in Yemeni waters “in conjunction with the Yemen cable landing party” – likely Houthi-controlled YemenNet.

“This maintenance event had been in planning for the past three months and was notified to all relevant parties and was completed successfully within the agreed maintenance window,” the company said.

Pioneer Consulting’s Clesca tells DCD it’s likely that any repairs to the damaged cables in the Red Sea will be made with the protection of warships; he doesn’t think they will remain unfixed for months.

“A few years ago, when piracy was a problem, it was a simple measure to have armed guards on board. But here in the Red Sea, if you want to protect yourself, you may need heavier protection,” he says.

The International Cable Protection Committee (ICPC) released a statement urging calm to allow the cable to be fixed.

“It’s a very unique scenario,” says Kentik’s Madory. “But the circumstances that led to that ship being attacked, that could happen today. The threat is continuing, they’re still shooting at ships. We’re not out of the woods.”

The long-term danger, however, is that even if there is a ceasefire in Israel, the Houthis will continue to attack shipping lanes in the area. Askari’s Milliken says the attacks have been “beneficial” to the group, and even after a ceasefire in Gaza, could continue attacking ships, and even shift to a more profit-focused piracy model.

“I don’t think it in their best interest to stop right now,” she says. “I think they're getting too much domestic support out of it that they wouldn't stop even if Iran compelled them to. They have more than enough capability stockpiled to continue on alone.”

That could, however, lead to a more “widescale response” from international forces looking to pacify the area and help business return to usual.

“Should military tensions in the Red Sea heighten, the possibility of the Houthis undertaking such actions increases,” says Crisis Group’s Nagi. “[But] this could lead to negative consequences for the Houthis, underscoring the complex implications of regional conflicts on global connectivity.”