How did Egypt come to be the Middle East’s primary data route?

To understand that, we have to head back - way back - to the mid-1800s. At the time, communication between Egypt and Europe traversed through Turkey, while telegraphs to Asia went from Egypt to India via the inventively named Telegraph to India Company.

This feature appeared in the latest issue of the DCD Magazine. Read it for free today.

Messages moved slowly and expensively across the land, making the British government's management of its vast realm a challenge. The world’s largest empire was constrained, unable to quickly respond to issues at its periphery.

Long routes had much greater latency, but also cost significantly more - at each intermediate point you would need a 24x7 mission-critical manned station. There, someone would have to manually resend the message to the next hop along the chain.

In an effort to speed things up, the SS Queen Victoria set sail in 1860 to lay a government-operated cable between the British-dominated territories of Myanmar (then Burma) and Singapore. Sadly, the ship sank before it had left the English Channel.

Next, in 1868, the government funded a cable that stretched from Egypt to what is now Pakistan, but it soon failed, leaving the government in debt.

"The government had also got burned on the first Atlantic cable and on the cable to Crimea," submarine cable historian Bill Burns explained. "So it became almost entirely a private industry, with the government sometimes giving a guarantee of a certain amount of traffic."

For the Europe-Asia effort, salvation would come in 1869, thanks to a seminal submarine cable figure, John Pender. A British Member of Parliament, Pender would found 32 telegraph cables, connecting many of Britain's willing and unwilling subjects around the world, as well as the US.

He created multiple different companies due to the high risk of cable laying in the day, insulating his other operations from the financial impact of a broken system. Once they proved successful, he would merge them into one conglomerate that eventually became Cable & Wireless.

In 1869, Pender formed the British Indian Company, acquiring the rights from the Telegraph to India Company.

His cluster of interconnected businesses then set about connecting Egypt to Yemen and India, and onwards through to Malaysia and Singapore, as well as Australia a year later. They would go on to be known as the Eastern Telegraph Company.

On June 11, 1870, the first message was sent from Falmouth, UK, directly to India. It passed through Egypt.

"The system of submarine telegraphs which is generally known under the name of the ‘Eastern’ may truthfully be said to be one of the greatest monuments of British enterprise and perseverance that the world has ever seen," the 1894 trade paper The Electrician says in breathless colonial prose.

The opening gave unprecedented access to the East. "The Earl of Mayo was murdered in the Andaman Islands, and the news was confirmed by a special message brought through the submarine telegraphs in a few minutes (February, 1872)," The Electrician recounts.

"During the war in Afghanistan in 1878, 1879, and 1880 the Government made large use of the telegraph, and the British public was enabled to read full details of all actions almost as soon as they took place."

Already, though, the dangers of a single route were clear. The Egyptian war of 1882 brought down landlines in the country, heralding months of outages where the British government could not communicate with India and beyond.

"The inconvenience of these total interruptions to the Governments and telegraphing public, as well as the loss of revenue sustained by the Companies showed the management the absolute necessity of duplicating and triplicating the communications," The Electrician states.

But despite all its wealth and power, the British government and Pender made a decision on redundancy that was based on minimizing distance rather than route diversity: It simply built another cable through Egypt in 1882.

"It is the obvious route through the Mediterranean," Burns said. "You want as little land as possible - remember, in many places, the nature is so hostile, the terrain so impenetrable. To put it bluntly, if you tried putting in a landline telegraph in most places you might find your poles disappeared in short order."

The cable operators primarily stuck to land that had already been carved out by the great railway endeavor, running parallel to the tracks that ran up and down Egypt.

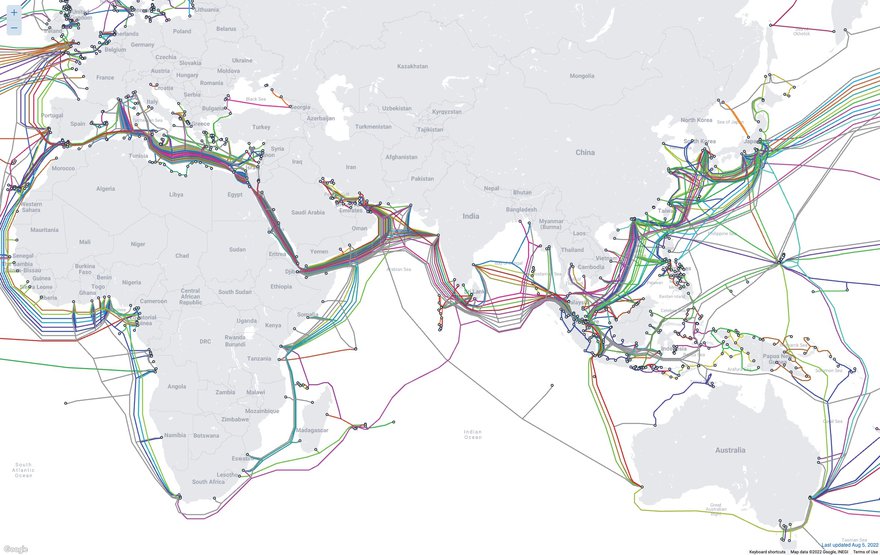

Little has changed, in Egypt and elsewhere, Burns said, producing a map of the Eastern Telegraph company's network in 1901. "If you look at a modern cable map, there's not much different."