The world's largest cloud companies all want to use their immense platforms to define the future of gaming.

This week, as we see the long-expected announcement of Amazon's cloud gaming platform Luna, it's worth looking at what such platforms can actually offer, and what that means for both gaming and this industry. It's especially fascinating for this author - someone who spent six years as a games journalist, before shifting to tech journalism, and then dedicating the last four years to data centers.

A new player has entered the game

First, let's look at the new entrant - 'Luna.' A date has not been set for the launch of the AWS-hosted platform, but it will initially be available on PC, Mac, Fire TV, and iPhone and iPad (using web apps). It will first launch in the US.

While Luna is the name of the overall streaming service, it will also have 'channels' that users can subscribe to. The main one is Luna+, which will cost $5.99 a month (introductory price) for a rolling selection of games. Other channels, including one by publisher Ubisoft were teased, and will cost varying amounts and offer different games.

Games can be played with either a mouse and keyboard, Bluetooth controller, or Amazon's new "Luna Controller with Cloud Direct technology." Like Google's Stadia controller, it connects directly to your WiFi router rather than through your computer, minimizing latency (more on that later) - with the company claiming time savings of 17-30 milliseconds.

Amazon also plans to lean heavily on Twitch, a platform for streaming game video for other people to watch, that it acquired back in 2015 for $970 million.

The company claims 17.5m people watch videos on the platform every day, and after Luna goes live, each video will have an option for people to start streaming the game - if it's on Luna - instantly. It is likely that Amazon will offer monetization incentives to streamers to get their audience to convert to Luna, turning people that viewers trust into handy salespeople.

But the cloud gaming service will mark a major foray into one of the few entertainment industries that Amazon has struggled to crack. Back in 2012, it launched Amazon Games Studios to develop its own titles, but has seen limited success with mostly smaller titles.

Crucible, one of its first AAA (the industry term for big-budget) titles, launched in open beta earlier this year but was quickly pulled and its release delayed due to poor reviews. It has another massively multiplayer online game, New World, that was set to launch this May. Then in August. Now it's set for 2021.

Layoffs were announced at the company's three game studios last year, and it's fair to say that Amazon Games has not been able to pull off the same critical success as Amazon Prime Video's studios.

Amazon also has its own video game engine (the software environment used to develop games), called Amazon Lumberyard. Based on the architecture originally developed by Germany's Crytek, Lumberyard is free for developers to use - as long as online components are served through AWS. The company also launched an AWS-based set of APIs known as 'GameOn' for developers to add leaderboards, leagues and competitions to games that can include real-world prizes (provided and delivered by Amazon).

Finally, it has its e-commerce store, where people can buy games physically and digitally. Digital sales figures are not known, but are not thought to match that of the game-focused Steam store, or upstart Epic Store.

Suffice to say, while Amazon has some presence in the games industry, it is small. It currently lacks the ability to develop and publish a large number of high-quality games, and building such an infrastructure is something that takes many years. However, in Twitch it has a huge marketing platform, while its e-commerce site can be used to promote its controller or give free trials to Prime subscribers.

The frontrunner

There's only one company that has the scale to publish lots of games and deliver them over its cloud service, and that's Microsoft.

Hundreds of millions of gamers have bought Xboxes over the years, with around 90 million of them currently paying for the privilege of online services with Xbox Live. Of that, some 15 million subscribe to Xbox Game Pass, which gives 'free' access to numerous games, including most of the titles it publishes itself, as well as third party-published games.

This month it launched Xbox Game Pass Ultimate (if there's one negative about Microsoft, it's naming structures), which bundles Live and Game Pass together for $14.99 a month, and throws in xCloud on top of it.

The service debuted in 22 countries a week ago, and comes ahead of Microsoft's big console launch this November.

While the company has more than a dozen in-house games studios (developing titles like Halo, Forza, and Gears of War), it has also been on an aggressive acquisition spree to bolster its portfolio. First, there was Minecraft's developer Mojang back in 2014, then came Obsidian, Ninja Theory, and InXile in 2018, and Double Fine in 2019. This month saw its biggest move yet: The $7.5bn purchase of publisher ZeniMax, which will bring huge titles under Microsoft's umbrella, including the popular Doom, Elder Scrolls, and Fallout.

Altogether, Microsoft has just under 30 studios (once the deal is approved), as well as numerous relationships with studios it pays to develop games by doesn't own. The company has also indicated it's still looking to expand, and is open to more acquisitions.

For developers, such commitments are vital to gaining their trust. No studio wants to spend three years developing a game for a platform that won't exist, or won't have players, by then. With Xbox, developers and publishers know that there'll be gamers in the droves, and even if xCloud isn't a huge success, the game will be able to be sold on the local Xbox platform.

Oh, it launched already?

Luna executives are likely to be cautiously analyzing the failure that is Google Stadia, at this time. The service launched last November to moderate fanfare, but has since failed to garner much attention.

The technology itself saw a mixed reaction, but the primary critique has been its games library. The platform has few titles, and a year on Google has yet to announce any major titles for Stadia, with the paid service primarily offering access to PC games that have been out for some time. It also has a free offering - that is, it's free to go on Stadia, but you then buy the games individually.

Players have been given little reason to use the platform, and its benefits are poorly communicated. Gamers can be an intensely loyal group, prone to aggressively cliquey fanbases, but Google has barely tried to foster any following.

There's still time to turn things around, but so far Google doesn't even appear to be trying. Major gaming conferences have passed without the company showing off its product. Given Google's well-known propensity for trying tons of things, and then canceling the ones that don't prove popular, developers and subscribers are likely put off investing time and money into something with so little support.

As for in-house development - Google opened its first game studio in 2019, the same year it launched. Another opened this year, giving it a paltry two studios that will likely need years to get up to speed. With traditional console platform launches, the general idea is to have that ready before the launch.

The company also said it would use YouTube Gaming akin to how Amazon plans to with Twitch. They promised various engagement tools to allow YouTube creators to play with their audience, ensuring that YouTube's large community does the marketing for Google. On top of that, links to play the games were to be embedded across a variety of platforms like Twitter, Discord, and Google Search.

Most of that has yet to happen. Even Googling 'Stadia' brings a webpage that gets people to fill in a lengthy registration form rather than providing an instant taste of the potential service.

The dark horse

Then there's Sony, which has the opposite issue of Google - it has the audience, with the wildly popular PlayStation console (currently more successful than the Xbox); it has the games, with the critically acclaimed PlayStation Studios; and it has subscribers with the successful PlayStation Plus service.

But unlike Amazon, Microsoft, or Google, it does not own the means of production. The company leases space in colocation data centers, but cannot ever expect to match the tens of billions of dollars of cloud infrastructure spend that its rivals are investing on a yearly basis. Microsoft can afford to set a few racks aside in each of its data centers for some xCloud servers, because it is building the data centers anyway - Sony just can't compete.

Despite being early to the game streaming market with its acquisition of game streaming startup Gaikai for $380 million way back in 2012, its PlayStation Now service does not have the same infrastructural reach as the cloud giants. It is also subject to frequent outages - with the entire PlayStation Network going down for four hours this week, for example.

For this reason, Sony did what many industry observers would have considered unthinkable just a few years ago - it sought help from long-time rival Microsoft. In 2019, the two companies signed an MoU to explore the joint development of cloud gaming services, hosted on Azure. The services themselves will be separate, but much of the backend will be the same - putting Sony in the uncomfortable position of funding its main competitor.

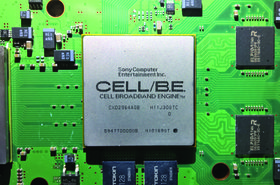

It is also not clear if Microsoft will afford Sony the same advantages it gives itself - xCloud is hosted on custom servers, each essentially four Xbox One Ss (upgraded to the new Series X next year). It is not known if it will allow custom PlayStation servers in its data centers, or just give it access to its standard cloud hardware.

The company as a whole also can't match the deep pockets of Microsoft. Its own game studios are generally recognized as being among the best, developing critical and commercial hits like The Last of Us, Spider-Man, and God of War. And, while the company many never reach its Walkman-era largess again, PlayStation has helped the company return to a $100bn market cap after languishing at a tenth of that just eight years ago. Profits are up, confidence is up - but few expect the company to be able to make the same multi-billion dollar acquisitions as its rival.

Luckily for the company, however, it may not have to counter Microsoft immediately. There's time.

Do we need cloud gaming?

While the tech giants are rushing to create a 'Netflix for games,' it still remains to be clear if there is actually a large appetite for cloud gaming.

Broadband speeds have not increased in the US (and elsewhere) as rapidly as many hoped, a real problem considering even a small amount of latency can make a video game unplayable. While a user can just pause a traditional passive video stream and let it load, in a game there needs to be a constant back and forth between player and data center.

Lag metrics are poorly defined, but it is generally accepted that more than 50ms of latency is noticeable to players (20ms is seen as ideal, above 150ms as unacceptable). When you add in the other causes of latency - processing time, controller latency, display latency, and multiplayer connection latency - the amount of time left for the cloud streaming service is a fraction of that.

This means that the data center has to be close to the user, and that everything has to be going well, with ideally no one else in the home watching Netflix or equivalent. With Stadia, despite Google's vast sprawling infrastructure, the reality has proved mixed. Many, despite meeting the alleged minimum bandwidth requirements, have struggled to play a game at sufficient quality.

The other issue is price. Cloud services have pitched it as a sensible alternative to spending thousands on a PC gaming rig. There are several problems with that analysis.

One is that those most likely to try out a new platform are the early adopters who are willing to invest in their hobby. Another is that people with faster broadband speeds are statistically likely to be more affluent. Then there's the fact that gaming consoles aren't prohibitively expensive for many, with Microsoft's cheapest new system retailing at $299. Current gen consoles are cheaper still, and second-hand models and titles are even less (plus they can be resold later).

The other sales pitch is convenience, where there is some validity. We're used to being able to watch a YouTube video on our phone, move over to the couch and watch it on the TV, and then pick it up later on a PC. Why shouldn't we be able to do that with gaming? Why do we have to be tethered to a console box or PC?

There's a limitation to that analogy, though. While splitting a 10m video between my phone and TV isn't a major hassle, the more immersive nature of gaming generally leads to longer continuous engagement, so you're less likely to engage with it in the same way. You might bring your phone into the kitchen to continue watching a movie while you cook or wash up, you might not do the same with a game.

Another convenience of cloud is the promise of no lengthy downloads or updates to games. Again, there's truth to this, but with caveats. Game downloads are annoying - but they're less annoying to the high-bandwidth users cloud companies are targeting - and smart downloading systems that update games while you're asleep, or preinstall titles before they officially release has made the experience easier.

But none of these reasons are the real causes for cloud gaming's soft debut.

It's about the games

This is so obvious that I barely have to say it: Gamers need games.

For all the talk of the 'Netflix-of-games' it's curious that cloud gaming companies don't seem to understand what makes Netflix popular. It's not the platform, it's the content. Having a platform that can stream videos is the bare minimum to compete, but people come back for the content. Crackle offered video streaming years before Netflix, but people do not Crackle and Chill.

With Stadia, and possibly with Luna, they seem to be making the mistake of believing that by solving the technical challenge of cloud gaming they have guaranteed success. The technical challenge just means that people can play on your platform, it doesn't mean that they should.

It's why Nintendo (which so far has no cloud gaming aspirations) has managed to sell consoles that were technologically inferior to its rivals - it created games people wanted to play.

Microsoft also knows how to make games people play, and will likely prove successful in making Xbox games, offering them on cloud, and slowly converting players to it as broadband speeds increase.

But they're not going to make a game that embraces the cloud. Ironically, this is where Stadia and Luna have more opportunity. Microsoft's focus will be on games that run on Xbox, so even if cloud fails they will be fine.

Unburdened by the limits of a single console, Stadia and Luna have the opportunity to make games only possible on cloud. It's something Stadia hinted at when they launched last year.

"We will be handing that extraordinary power of the data center over to you," Google VP and GM Phil Harrison said at the time. He joined the company last year from Microsoft, and previously spent a long time at Sony Computer Entertainment. "With Stadia the data center is your platform, there is no console that limits your ideas."

Unique games only possible with cloud gaming could change the playing field, finally giving consumers a reason to shift to it. There's a lot riding on that 'could' though - countless platforms have languished waiting for that killer app to turn things around. And, currently, there's no indication that Stadia or Luna are putting the money into finding those unique titles.

Should it happen, or should the slower 'console plus cloud' approach of Microsoft, prove successful, however, it would mark a stark change for gaming.

The data center would be the next console.

That's where you come in

You've made it this far, and you've read a whole bunch on Doom, Twitch, and PlayStation Plus. But this is DCD, a publication about data centers, let's get back to the heart of the matter: Internet infrastructure.

Simply put, to pull this off, we're going to need more. More data centers. Closer data centers. More fiber. Faster fiber. More interconnection. More servers. Faster chips. Better compression technology. Just so much more.

While, as is a common disconcerting trend, a lot of that 'more' is going to be consolidated in the hands of a few tech goliaths, there's space for others to benefit.

Cloud providers already buy countless millions of square feet of wholesale data center space, and this will only add to that. With latency such a huge requirement, expect smaller deployments of gaming servers in even more locations than their general cloud distribution.

Think of it like Amazon CloudFront, the company's CDN that is currently around 138 access points (127 edge locations and 11 regional edge caches) in 63 cities across 29 countries. That's a lot more than its 77 cloud Availability Zones across 24 geographic regions.

They're going to need help finding somewhere to put all these servers.

This could also have a knock-on effect on the wider Edge market, an industry desperately in search of its own 'killer app.' Putting some game servers close to a user may lead to people thinking up reasons to put other servers there too.

They have time to think, too. Anyone that tells you this is the 'next big thing' has something to sell. This could be the future of gaming, but we're still a long way from this hitting critical mass. The tech has a way to go, and the reason to use it has a lot further to travel.

But now that all three cloud giants have officially unveiled their offerings, we should start to get a real idea of what's to come. The game has only just begun.