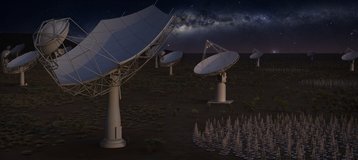

Design work has been completed on the Square Kilometre Array's two supercomputers.

With the world's largest radio telescope set to be built across two nations, South Africa and Australia, the SKA will need local supercomputers in Cape Town and Perth, known collectively as the Science Data Processor (SDP).

Once built, the array will be the world’s largest public science data project. Construction on SKA1, the first phase, is expected to begin this year.

Processing space

“We estimate SDP’s total compute power to be around 250 petaflops - that’s 25 percent faster than IBM’s Summit, the current fastest supercomputer in the world,” Maurizio Miccolis, SDP’s project manager for the SKA Organisation, said.

“In total, up to 600 petabytes of data will be distributed around the world every year from SDP - enough to fill more than a million average laptops.”

Some 5Tbps of data will flow through SDP, requiring the system to make near real-time decisions about what data to keep and what to discard as noise.

“By pushing what’s technologically feasible and developing new software and architecture for our HPC needs, we also create opportunities to develop applications in other fields,” Miccolis said.

But before data reaches the SDP, it first goes through the Central Signal Processor - hardware and software inside the SKA itself that converts digitized astronomical signals detected by SKA receivers (antenna & dipole -“rabbit-ear”- arrays) into the information that is sent to the SDP. The SKA Organisation notes: "It will be located in remote locations and must be designed to deliver the maximum science possible within a hard cost cap and an aggressive timeline."

“SDP is where data becomes information,” Rosie Bolton, data center scientist for the SKA Organisation, explained. “This is where we start making sense of the data and produce detailed astronomical images of the sky.”

After initial processing and filtering in the SDP, the SKA data will be sent to regional supercomputers around the world, including the Barcelona Supercomputing Center and the Jülich Supercomputing Centre.

Bolton added: "The [SDP] architecture has to be able to evolve over the 50-year lifetime of the project. So we have to design a system that's highly scalable and highly extensible so that we can add on modules and change the size of it as time goes on."

The SKA telescope is expected to be powerful enough to detect very faint radio signals emitted by cosmic sources billions of light years away from Earth, those signals emitted in the first billion years of the Universe when the first galaxies and stars started forming.

The SKA Organisation anticipates that the array will be used to answer fundamental questions of science and about the laws of nature, including: how did the Universe, and the stars and galaxies contained in it, form and evolve? Was Einstein’s theory of relativity correct? What is the nature of ‘dark matter’ and ‘dark energy’? What is the origin of cosmic magnetism? And, is there life somewhere else in the Universe?