VDMA, a group of German and European engineering firms, has warned that a proposed Europe-wide ban on PFAS chemicals would have a "devastating" effect on European industry.

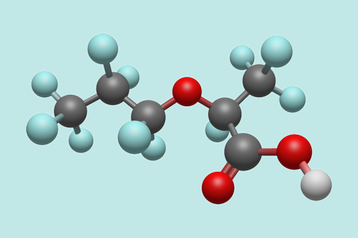

A planned European ban on per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), also known as "forever chemicals" would endanger many industrial processes, including those needed for a transition to clean energy, according to a position paper from VDMA. The group wants to see a more differentiated view of the substances, to allow their use when needed.

PFAS are widely used in industrial production. In the high-tech sector, they are essential in silicon fabrication. Within data centers, they have been adopted as working fluids for two-phase liquid cooling by pioneers such as Zutacore and LiquidCool. The leading producer, 3M, has announced it will pull out of the field, and cooling specialist Zutacore has announced a shift to an alternative producer by 2026.

Europe is working on a comprehensive ban of around 10,000 substances, which VDMA says would be a mistake as the list includes chemicals that are "indispensable" in technologies including the production of fuel cells, heat pumps, solar systems, and hydrogen electrolyzers.

According to the VDMA, the planned European ban is based on concerns about consumer products such as ski waxes, Teflon pans, and outdoor jackets, and an industry-wide ban would be "as exaggerated as it would be unjustified."

VDMA wants to see some PFAS classed as "polymers of low concern," and exempted for their use in industrial production, warning that otherwise, the EU will "shoot itself in the foot."

"The planned ban would mean that European producers would have to do without PFAS, while competitors from non-European countries could continue to use the substances and thus gain considerable competitive advantages,“ said Dr. Sarah Brückner, head of VDMA environmental affairs and sustainability.

VDMA points out that goods produced with PFAS would still be imported into Europe, as there are no standardized tests for them and little understanding of the supply chains.

Dr. Brückner said Great Britain has a better approach: "We should take our cue from the UK and look at the substance groups in a differentiated way."

The VDMA wants PFAS separated into subgroups, with non-hazardous polymers immediately exempted. The group also wants PFAS to be allowed in industrial applications, where safe handling can be enforced. PFAS should also be allowed in the internal workings of systems, which do not come into contact with the environment, VDMA says.

The group also calls for a longer transitional period than the proposed 18 months, so alternative chemicals can be found - and wants to allow PFAS replacement parts to be allowed indefinitely.