Who is most important on the mobile Internet? People or devices?

We are already outnumbered more than two to one on the Internet of Things, which this year apparently connects more than 13 billion devices, while there are only five billion humans on the Internet, which is around 63 percent of the world's population.

That gap is set to widen. By 2030, there will be around 30 billion connected devices, and an absolute ceiling of around 8.6 billion people for people, because that's the expected population in that year. .

But a person and a device are very different things.

Sensors don't get sassy

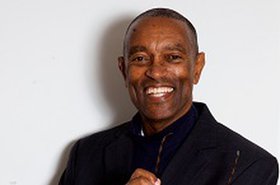

Peter T Lewis has a good perspective on the relative roles of people and devices on the mobile Internet - given that he coined the term "Internet of things", and predicted a mobile Internet of connected devices as long ago as 1985.

Back then, the mobile phone was still taking off, he told me in DCD's latest podcast. He's helped found Cellular One, one of the very first US cellphone companies, and was busy getting people - including Ronald Reagan - to adopt the brick-sized phones.

But he wanted to connect devices as well: "I predict that not only humans, but machines and other things will interactively communicate via the Internet," he said back in 1985, predicting devices and sensors could make our lives easier - for instance, by enabling gas stations to order a refill when their tank falls below a predetermined level.

Connected devices already existed then, of course. Before the Internet existed, traffic lights were linked up and synchronized, and the potential hazards of this were dramatized in one of Lewis's favorite films, The Italian Job, in which British crooks steal bullion in Turin by hacking the traffic light systems to cause a chaotic traffic jam.

But Lewis saw that the Internet would provide a low-cost ubiquitous linking method, and cellular phones would eventually offer a reliable widespread underlying network that could enable virtually anything to be connected.

He doesn't claim any credit for developing the IoT concept into reality. He mentioned it in a conference paper - for the Congressional Black Caucus Foundation - and then went back to his day job, of developing the cellular industry.

At that stage, the priority was connecting people, both consumers and business folk, and they weren't easy to deal with: "I gotta tell you, consumers are a real pain," he told me off air. "You give a cellular phone to a consumer, and you'd have complaints."

People would call tech support and say "Ever since we got your cellular phone, in the morning, when we make our wheat toast, it comes out burnt. I think the radio waves are having an effect on our toaster." Lewis says cellphone signals were blamed for everything including cars carshing and catalytic converters failing.

Was that why he wanted to connect devices instead? "You're absolutely right. A red light or a gas station pump can't talk back to you."

Ambivalent industry

The possibility was out there in 1985 - and in some ways sensors and devices would have been a better fit than people, for 1980s mobile networks, as sensors didn't need much bandwidth. A gas station tank could send a useful signal about its status with as little as one bit, telling whether it was filled above a certain level

People were more demanding, but that was where the money was.

The IoT concept was independently conceived in 1999 by Kevin Ashton, who went on to co-found MIT's Auto-ID Center, and after this development proceeded.

However, for the first ten years of the century, people continued to take center stage, as mobile phones reached a saturation level in many countries, and the industry concentrated on ways to get more business from people by adding data services, such as mobile Internet and gaming.

People changed from consumers of tiny voice and data streams to addicts connected to a hosepipe of streaming data. Somewhat ironically, people were taking the data, while the modest needs of sensor-based IoT were developing quietly in the background.

Around 2009, Cisco noticed that there were now more devices than people on the Internet - the ratio grew from 0.08 in 2003 to 1.84 in 2010, according to a Cisco white paper.

After that point, operators started to look on IoT more favourably - seeing it as a savior, a welcome new revenue stream which would continue expanding when people reached saturation point.

Since then, there have been a plethora of IoT issues to resolve, including what underlying radio technologies are involved and what security protocols are enforced. The warning of The Italian Job still stands. and has become more significant, as more items are connected, including data center equipment .

Government regulations have added a layer of difficulty, and different operators have attempted to stake out areas for their own use with proprietary systems.

But overall, IoT is growing rapidly, and can realistically claim to provide a massive new market for operators - because they have found a way to encourage those devices to produce and consume more data.

Big Edge data

A traffic light originally only needed a few bytes to receive instructions and transmit its status, but now it will be transmitting the status of its electronic equipment to schedule maintenance. It will be downloading software updates. It will be detecting motion for safety reasons, perhaps tracking number plates with cameras, and maybe using facial recognition for the police department.

Video is core to these expanded demands, and systems like connected cars predicted to need to transmit multiple high-definition video feeds. McKinsey has predicted that truly autonomous vehicles will tranmit something like 500GB of data per hour, making them a more sought-after and profitable consumer than any human - and maybe the only thing that could justify the roll-out of high-bandwidth 5G networks.

With people peaking and devices continuing to expand their data needs, it's easy to see that for operators and tech firms, devices will be their most significant customer.