When it comes to sustainability, it can begin to feel like the conversation is a broken record. We aren’t doing enough. We need to do more, and we aren’t progressing towards this ‘more’ quickly enough.

But, perhaps the issue of speed comes down to a further issue of transparency – or lack thereof. Without full transparency, we cannot begin to really uproot the sustainability issue in the data center industry. Which begs the question – is focusing on carbon, and the PUE, limiting the overall transparency of sustainability?

At the recent DCD Planning for Hybrid IT broadcast, we sat down for a panel discussion about just this, and the solution that we need for greater transparency, and greater change.

Pernilla Bergmark, principle research of IT Sustainability impact for Ericsson kicked off the discussion with a look at the data. Data which, to be frank, presented some positive aspects of the outlook.

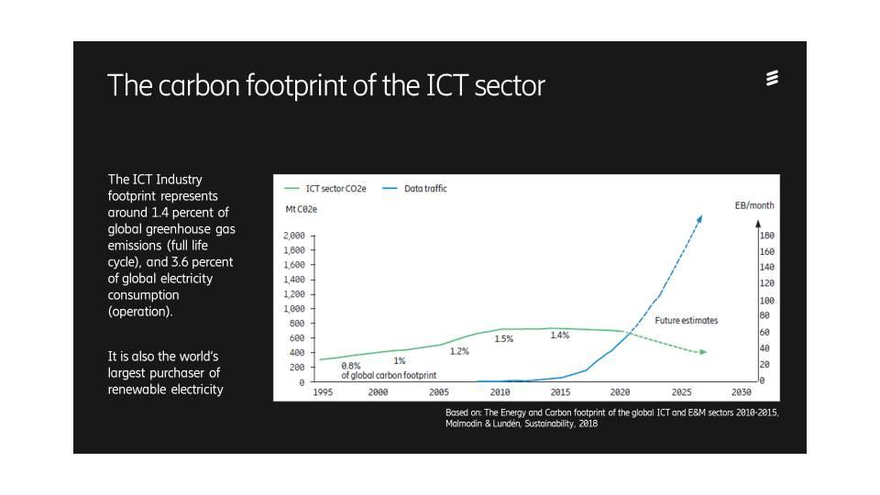

“We have a timeline, where we have followed the footprint here over the years, and we can see it's around 1.4 percent of overall global emissions. Based on our data set, we can also note from this picture that it has remained quite stable since around 2010, while we see that the data traffic has exploded.”

However, regarding this data, Jim Connaughton CEO of Nautilus Data Technologies, pointed out that it has to be viewed in context.

“It showed this remarkable growth of data and a gradual flattening of the energy consumption associated with that. Now, what's that about? That's because for 20 years, the sector has focused on the energy consumption of ICT infrastructure in the data center context driven by PUE. But with this singular focus on energy consumption, the servers have become a lot more efficient, while becoming more powerful.

“PUE has been so successful in driving this dramatic improvement, mainly inside the servers and those systems, and to a more limited extent in the data center itself. What if we broaden that in a lifecycle way, and talk about that concept. We've introduced the TRUE, total resource usage effectiveness, or true.

“For example, a lot of water is consumed in the data center to accomplish manufacturing chilling, mechanical chilling. That water has to be produced to the drinking water plant, which filters and pumps the water to the data center, and then that water energy is taken to use the water to accomplish chilling, and then there's wastewater that has to be chemically retreated and then put back out.

“So all of a sudden, now you have water entering the equation in massive volumes and you have energy for the production and treatment and carrying of the water which is not currently accounted for.

“You've got a bigger energy load than you were thinking about, as well as a water load that not a lot of consideration has been given into, which is finally emerging as an issue.

“Then, just the chemical management associated with running a data center is not something that's talked about much at all. Yet it's a source of failure, it's a source of liability. It's creating hazards for workers and creating potential hazards to the environment.”

It is, therefore, safe to say that we cannot merely consider the carbon footprint or the PUE when considering true sustainability. There needs to be a cyclical approach to the matter.

“This idea of life cycle thinking, life cycle assessment, needs to be brought more transparently into the sector. It's been well-practiced in many other sectors for a long time. But given the global reach, and the interconnectivity of the ICT sector, it is a big element of the sustainability footprint, both positively and negatively. So when you approach things it's all about understanding the weight of benefits and negatives and trying to balance as much as possible to the benefits.”

Deborah Andrews, associate professor of design at the School of Engineering, London South Bank University, is also looking beyond carbon footprint.

“What we're doing is not just looking at carbon footprinting and carbon equivalents within the project. We're focusing on the impacts of hardware and service, in particular, because they have the highest embodied impact. They include a considerable number of critical raw materials, PCBs, and so forth, which have a very high environmental impact.

“Traditionally, our life cycle assessment began by looking at energy consumption and embodied energy, and a good metric for that, of course, was carbon. But we find that that's really indicative once you start measuring the impact of all the various materials in products, or energy systems.

“So, in addition to carbon and carbon equivalents, you're looking at things like lithium-ion batteries, it could be tantalum or aluminium, all the various different materials, and products, right from the extraction of raw materials, through manufacture use, and then treatment at end of life, we find quite a different breakdown of our ratio between the operational and the embodied impact.”

For a deeper look into sustainability and transparency, download the full episode: