Data centers need to have a steady supply of electricity that comes from a sustainable source, which doesn’t pump CO2 or other greenhouse gases into the atmosphere.

A small number of organizations are starting to think that nuclear power could fit the bill.

Image problem

Nuclear power has an image problem. It’s tinged with its military origins, there’s a very vocal campaign against it, and nuclear projects all seem to be too costly, too late, or - in cases like Chernobyl - too dangerous

But countries like France rely on nuclear electricity, and are lobbying to have it classified as a clean technology, because it delivers steady base load electricity, without making greenhouse gas emissions.

Environmentalist George Monbiot has become a supporter of nuclear power, arguing that its health risks are “tiny by comparison” with those of coal. The Fukushima accident in Japan was an unprecedented nuclear disaster, but it caused no noticeable increase in cancer deaths, even amongst workers clearing the site.

Meanwhile, many are killed by pollution from coal-fired power stations - around 250,000 in China each year for instance - and that’s before we consider the greenhouse effect.

“The nuclear industry takes accountability for its waste,” says Alastair Evans, director of corporate affairs at aircraft engine maker Rolls-Royce, a company which aims to take a lead in small nuclear reactors.

“The fossil fuel industry doesn’t do that. If the fossil fuel industry had managed their waste in as responsible a way as the nuclear industry, then we wouldn't be having COP26 and climate conferences to try to solve the problem we're in now.”

Nuclear but better

For all its green credentials, today’s nuclear industry is all too often bad business, with projects that take far too long, get stuck in planning and licensing, and go over budget.

The UK has a new reactor being built by EDF at Hinkley Point, but it is terminally over-budget and late. Its output will cost €115 per MWh, which is double that of renewables. To make matters worse, its delay blights the grid and causes more emissions, because utilities have to burn more gas to make up for its non-appearance.

Rolls-Royce is one of a number of companies worldwide that say we can avoid this with small modular reactors (SMRs), which can be built in factories and delivered where they are wanted. Standard units can be pre-approved, and other approvals are easier because they can be done in parallel, says Evans.

“You don’t have to go back to government for a once in a generation decision like Hinkley Point,” he says.

Nuclear you can buy

They’re also easier to finance. At 470MW, Rolls-Royce’s SMRs will be a fraction of the size of Hinkley’s 2.3GW output, but cost less than a tenth the price, at around €2 billion.

[Note to the reader. Nuclear reactors normally quote figures for their thermal output in MWt and use MWe to refer to the amount that can be converted and delivered as electrical power. In this article, we will only refer to the electrical output, and quote it in MW for simplicity.]

According to Rolls-Royce's site, the SMR "takes advantage of factory-built modularisation techniques to drastically reduce the amount of on-site construction and can deliver a low-cost nuclear solution that is competitive with renewable alternatives."

“Like wind farms, the cost of a nuclear plant is all up-front,” says Evans. “And they give steady power for sixty years.”

A decommissioned nuclear plant in Trawsfynydd in Wales is being considered for the first of Rolls-Royce’s SMRs, and the company has spoken publicly of its ambition to build 16 in the UK. It’s reckoned that the Trawsynydd site could support two SMRs and already has all the cables and other infrastructure needed.

At the time of writing, there’s no official government policy on this, however, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson told the Conservative Party conference in September that nuclear power was necessary to decarbonize the UK electricity grid by 2035, as there is a lot of gas-fueled generation to phase out.

Rolls-Royce’s SMR program had some £200 million from the UK government, and £280 million from a group of investors.

Having achieved its matched funding, the Rolls-Royce SMR business will submit a design to the UK Generic Design Assessment (GDA) process which approves new nuclear installations, and will also start identifying sites for the factories it will need to build the reactor components. Where and when the SMRs themselves will land is not yet clear.

Learning from submarines

Other countries have been making similar steps, with Nuscale in the US getting government support for a small-scale reactor program (see box). In France, President Macron has pledged to fund EDF developing SMRs for international use.

The reactors are simplified versions of the large projects - most are pressurized water reactors (PWRs), and they call in experience from sea-going reactors, such as those in nuclear submarines.

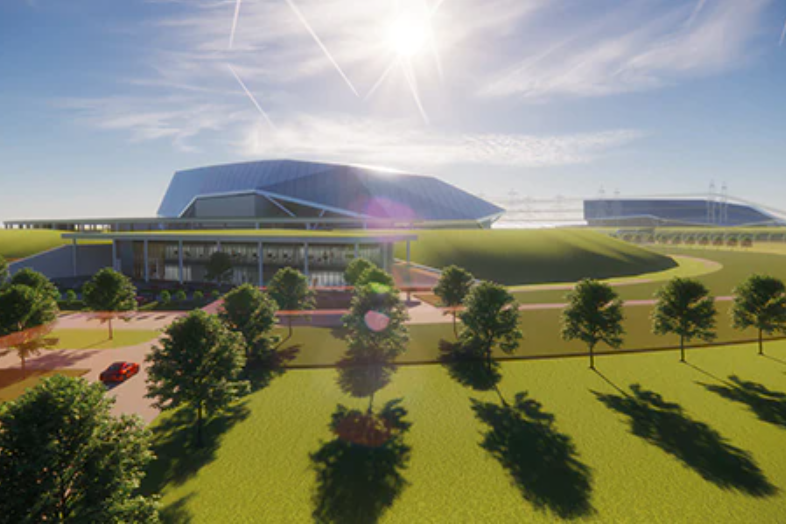

SMRs will be the size of a couple of football pitches. They’d be put together inside a temporary warehouse building which would then be removed, leaving the power station in situ.

These reactors have of necessity been made to be small, portable, and reliable. Nuclear sub reactors range up to around 150MW. French submarines are powered by a 48MW unit which needs no refueling for 30 years.

Russia’s SMR program is based heavily on nuclear submarine and icebreaker units - the state energy producer Rosatom has put together a 70MW floating unit, which can be towed into position offshore where needed.

In the UK, the first few of Rolls-Royce’s units will be paid for by the government. Subsequent ones will be available commercially, as the project has been “de-risked,” and it’s easy to get debt and equity to build more.

Ready to invest in

At that stage, Rolls-Royce would float off the SMR business as a standalone company, financed by equity investors, and start taking orders for new nuclear plants. The company hopes to get factories established in the next few years to start making the SMRs.

And that’s where data centers and other industrial customers will come in: “A user, say a data center, books a slot for a unit, and it rolls off the production line the same way you'd order an airplane engine.”

Why would people invest? This kind of nuclear could be much more viable than the giant projects. Rolls-Royce expects its SMRs to produce electricity at around €50 per MWh. That makes it as cheap as offshore wind power - but with the very important benefit that the power is delivered continuously.

If the whole of society is decarbonizing, then our need for electricity will expand. Heating and transport must be switched to electricity, and that means more electricity must be generated. And beyond that, the industry’s dependence on energy has been revealed graphically by the effects of the current hike in gas prices.

By providing long-term, guaranteed low carbon power which can support baseload without the variability of solar and wind power, SMRs could help support the decarbonization of industries.

A large amount of baseload electricity could also help foster other energy storage systems. For instance, hydrogen could be used as a portable fuel, but to be green it would have to be made by electrolysis using renewable electricity.

Benefits for data centers

“We are keen to present the off-grid application of stable secure green power to any and all carbon-intensive industries,” says Evans. By paying the costs of an SMR located nearby, a steelworks could switch to green electricity, and escape from increases in the cost of gas - while also reducing its emissions drastically.

Data centers should find this an easy market to participate in. Large operators like Google and Facebook are well used to making power purchase agreements (PPAs) for wind farms or solar plants: Rolls-Royce believes they could take a PPA for a portion of an SMR project’s output.

For a data center operator, a PPA for a portion of an SMR might seem a distinct upgrade on a PPA for a wind farm.

While the operator has paid for green electricity to match its consumption, the wind farm would deliver it at particular times, instead of when the data center needs it, so the renewable energy would be more of an offset for the electricity used by the data center, which would be made by whatever mix is actually on the grid at that time.

Data centers that buy a PPA for nuclear energy, on the other hand, would be able to just plug straight into the power station.

At that point, going nuclear provides the best of both worlds: as well as emitting no greenhouse gases, the data center would also be independent - free of the fear of blackouts on the grid.