In the second part of our interview with Leonard Kleinrock, the inventor of packet switching discusses the UCLA Connection Lab, what went wrong with the creation of the Internet, and how you continue to innovate after starting a revolution.

Find part one here, our interview with Vint Cerf here, and the delay-tolerant networking feature this was for in the magazine over here.

Sebastian Moss: I was watching your 'My work and my life' video where you mention the 'will your work be known in 100 years from now, or 1,000 years from now?' concept of tackling problems. Other than causing a minor existential crisis in me, for yourself, it's almost the opposite. When you help create something so impactful and see the enormity of that, the consequences, all the amazing things, and all the terrible things that came out of it. How does that not freeze you?

Leonard Kleinrock: You're asking does it bolster your ego so much? And does it frighten you?

Yeah.

It shouldn't bolster the ego because you didn't really do it. It was a collection of people who were going to happen. Maybe you've seen my commentary on Nikola Tesla - it was going to happen. Vint Cerf did not have to be born, nor did Bob Kahn, Larry Roberts, [J. C. R.] Licklider, nor anybody else. It would have happened. So you don't get so egotistical.

In terms of the enormity of it, again, it's grown, it's taken off, but due to many, many other people's contribution. You can contribute, but you don't have to shoot for the Moon, you can shoot for a satellite, if you will. But you should go after things which are worthwhile. By the way that the 1,000-year comment is due to Dick Hamming [the mathematician behind the Hamming code]]

He wrote a wonderful paper, it's called 'You and Your Research,' I believe it came out of Bell Labs. And he asked, why is it that the work of so many researchers is not known or followed or meaningful? And the basic answer is because they're not working on meaningful problems. And that's part 1,000 year question. You can't always predict, but you should act as if it is going to be remembered 1,000 years, and do the work carefully and well and thoughtfully,

Is the most promising researchers now might be some mushroom scientists, and 1,000 years from now that's all people eat.

You're right [laughs]

When you think about your legacy, you've got this big moment quite early on in your career. And it's kind of impossible to top that, without being rude. You're doing all this great research now, but that was potentially the top. Or is that an unfair way of looking at it?

At the time one didn't know it was the top. So it didn't discourage anybody saying 'my god.' That sort of happened to [father of information theory Claude] Shannon - I worked with him. He couldn't top that early work on entropy and coding theory.

It can discourage you if you're acclaimed so highly in the early stage of your career. But that didn't happen to any of us. It grew and grew. And then there were a lot of players, so it doesn't discourage me from the things I'm working on now. Some are smaller, some in my mind are larger, I like to find virgin areas which allow me to use my skills and still are relatively unmined.

That's one of the reasons I chose this problem early on cause nobody was looking at it. Then the field gets too crowded, as has happened many times in my career. For a while, you're publishing papers, and the people behind you are picking up the parts you didn't pick up and filling them in. And pretty soon when the literature gets so voluminous that you can't keep up, that's the time to shift.

Maybe a little a few degrees in an area, which uses your skills and is fairly related, but is new. And I've done that a couple of times. It's just more interesting. It's fun to break new ground.

Yeah. And it's also impressive to keep staying in the forefront for such a long career.

Well, yes, it keeps you going. You know, I'm not a young man now. But I'm working every bit as hard as when I was 30 years old.

Because you've been there for the creation of on the Internet, and its release, do you have specific consumption habits. Like [former Google CEO] Eric Schmidt stops his kids from using the Internet at times. Some people, don't try and Google something until they have 10 minutes to remember it. Is there a way you try to limit how it impacts your brain?

Well, yes, and no. Early on, when my kids were young, approaching teenage [age], PCs had just come out. So I gave each of them $4,000. I said, you have to buy a PC. And my son bought a Lisa, and my daughter bought a standard PC. My other daughter did not. She's a very famous journalist now. She still does not own a PC - and she never gave the money back, by the way [laughs].

But she doesn't have a smartphone. She doesn't have an email address. And she's a fantastic investigative journalist, works on Hollywood and fashion, everything else. So I tried to guide them without imposing much on them.

But two of them are scientists, one is a journalist, and one went into the movie business.

So there was not a lot of forcing them down a particular path. In terms of adopting new technology, heck, my granddaughter teaches me an awful lot about this cell phone, and how to use it. The kids are way ahead of people like me. So I like to focus on the things I do well, which is the research. I use technology all the time, but not in a more sophisticated fashion than pretty much anybody else.

I've got a well-equipped home here in terms of technology. But if you walked in here, you couldn't tell that I was a research scientist... unless you looked at my library.

So talk to me about the research you're working on now.

I recently opened up a new laboratory at UCLA. I call it the UCLA Connection Lab. And it's called that because I modeled it after the MIT Media Lab. You'll notice the sentences are parallel. Now, the MIT Media Lab, Nicholas Negroponte is a good friend of mine, he formed the lab with others. It was a lab, which was a collaborative research environment, interdisciplinary with an underlying theme. His theme was design, which is a very broad theme. Mine's the same.

It's an interdisciplinary, collaborative research facility for graduate students, undergraduate students, faculty, visiting scholars, researchers, etc., with an underlying theme - connectivity.

And it's a very broad topic that covers so many things. We look at the standard underlying Internet technology, wireless, Internet of Things, blockchain, some machine learning as used in connectivity systems, and a variety of others.

And so I'm focusing my attention now on promoting all those areas. But blockchain is a particularly interesting one. There's some very good research to be done there, both in the underlying cryptography side, which is not my expertise, but I have people in my lab who are. And in some of the performance evaluation; how well did these networks perform, how much throughput, what's the response time?

And looking at systems of evaluation, I'm very much involved with what's called a Reputation System, to try to evaluate the value of the consensus votes that are coming in. How much weight do you give to each vote, if you will, for agreeing that a transaction is valid? And it's not unlike the PageRank algorithm from Google, where everybody involved is evaluated and everybody else with different weights.

So that's an area which involves graph theories and communication theories and performance evaluation. And yet is not networking per se. But it's connectivity.

On Blockchain: With the Internet, you had a few decades to just work on it, and then the capitalists came along. With Blockchain, it feels like the capitalists came along before the technology.

You're exactly right. And it's a big shame, because it hasn't had a chance to mature from a technology point of view. It's being driven so much by as you say, the get rich quick, and, and they've therefore brought in the malicious plays immediately for that reason. And so it is a huge difference between the two, we had 25 years to curate the internet before it went profitable, if you will. And even then the Internet is having issues. So you are exactly right. it's a concern.

It's like as a journalist, I'm generally dismissive when someone talks about blockchain. I think 'Oh, here it goes again, what are they trying to sell me?' And I think it's unfair to the core science behind it, but because of those people, it has this aura.

It definitely has. And yet it has all the nice technology properties of being distributed, and hopefully being not influenced by a central authority. Of course, in terms of the applications, things like smart contracts are great.

The idea of being able to move money in a trackable way. The notion of irrefutability is pretty much there. The fact that is a distributed system is always very attractive. Any distributed system is like a honeypot to me. I just want to look at it.

Do you think it's ever possible to have a truly distributed network? We're a hoarder species, if people can get more of something than anyone else they will.

You're thinking about the human hoarder phenomenon? You're right. Hoarding is one, I think competition or tribalism is a similar phenomenon. And you're right, that's pervasive in human nature.

It starts with sibling rivalry, even parental rival the mother versus father kind of thing. And so I don't think we're ever going to avoid that there's going to be confrontation. And in some sense, there's a benefit to that, because it keeps you sharp, and keeps you striving to become further excellent. But when it gets out of hand, and you get nation-states competing with each other, as has happened now in the Internet, that's really worrisome for a lot of reasons.

The consequences are huge. The power they have to inflict control is enormous. And if we get these splinternets, the balkanization of the network, and then you don't get free flow across the worldwide Internet, you've lost a lot of the fundamental capability and benefit of the Internet.

And I do fear and worry about that, because we're beginning to see it happen.

It's again, finding the right amount. ARPANET wouldn't have been created without Sputnik, the fear of the Soviet Union, and all the funding that went into it. But it wasn't enough fear to end the world, luckily, even if it got close. And now with the fear of China is the only reason the US government is passing any kind of investment in science bills. So a little bit can be good, but it's just heading in the wrong direction right now.

You're correct. The general public would not be supporting science, per se, unless they get the right education as youngsters and begin to appreciate the wonder and the challenge and the benefits.

You know, when you teach somebody something as beautiful as Archimedes' principle... I mean, there's something so delicious about it, and so surprising about it. It's got to excite some genes in you somewhere to look further.

I like to make the point, maybe you heard that in My life and Works talk that the students of today don't realize that they've been given an enormous gift of 4,000 years of the world's knowledge - for free! Here's Maxwell's equations, here's Archimedes' principle. Here's the Mona Lisa, The Great Gatsby. Here it all is. And unfortunately, it's given so freely, they don't realize the value of that gift.

And it also deceives them because it looks as if it's easy to make these breakthroughs. Here's Maxwell's equations, go ahead and use them. Wow. Well it wasn't easily created. And so they believe it can be done easily. If they tried to do it they bump into a brick wall, and they get discouraged. And the next step is you have to teach them you can get through with little steps, sometimes big steps. But don't get discouraged. So there's a whole lot of teaching you have to do.

And that doesn't happen in a typical education system these days. The value of the education, the fact that knowledge can be improved and engaged.

In such things, you'd think there'd be this HG Wells' World Brain idea of once you get to that point of open access knowledge to everyone the speed of research would just go through the roof.

Yup.

Is it almost we failed what the Internet should have been? There's a lot of talk about what the Internet does, what it's almost what we've done to it.

In a way. The average citizen doesn't have to understand how it works. But the applications that people are attracted to... I mean, TikTok...

And yet, I see my granddaughter out there in my backyard here, dancing around taking videos, constant selfies... this whole selfie thing, look, I'm another generation, selfies are the ultimate form of narcissism. Why you would constants you take pictures of yourself, I don't know. But it's the fashion these days. So I'm missing something, obviously, I don't understand what the real motivation is. It's not just pure greed and narcissism, there's something else attractive about it. And in those things, you can't control but they're gonna emerge.

I mean, we've crossed so many random subjects. I was just wondering if there's anything else that comes to mind about this, or DTN?

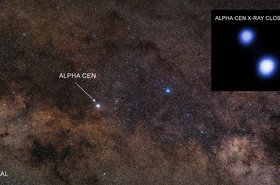

I haven't thought too much about the ethics and the impact more about the challenge of the science. I guess I wonder why it's taken so long for any significant progress. Is it because of a lack of launch capability, or that the science has not been able to move forward enough?

It seems to be the stuff that we have sent out there doesn't need it, so why bother? Why risk it? They've done the trials, they've done a little test on the ISS, on the Martian rovers. But until you have enough network devices out there in space... It's like the chicken and the egg, why invest in building the infrastructure for a lot of devices, and also why put a lot of devices out there without the infrastructure?

Let's make sure that Bezos does not come back, and then he'll invest money to bring him back.

I think you still have that psychology of 'why are we doing this unless it directly helps us?' And it's just this the failure to translate to the populace, that there is a benefit. And even if there isn't, just doing it for the sake of science and knowledge is enough.

It is but a lot of the population doesn't believe in that.

Yeah.

You know, you mentioned Sputnik and Eisenhower. His recognition, as I understood it, was that the United States had failed in its leadership in science - not that we were threatened that Russia is going to attack us. Although who knows what at the higher level gave them motivation. All he wanted to do was bring up our capability, not our defense against a nuclear attack. Now they go hand in hand, it's true.

But he was smart to present it as raising our capability as scientists and engineers, as opposed to military operations. There's an interesting argument as to why the ARPANET was built. And there's the urban myth that it was built to protect us against a nuclear attack. And it is a myth - none of the researchers down at my level, or even at the program level of ARPA were about military applications.

However, if you go up the chain, the director of ARPA, to Department of Defense, to the White House, they must have been thinking about what the military applications are. So, in some sense, the myth is true. But at the people doing the work, there was no pressure, no understanding, no care about any military applications. Not in those early days anyway.

I think at the upper level, it was just all crazy. I'm not sure if you've read Daniel Ellsberg's The Doomsday Machine.

No, I haven't.

So in that, there was a paper sent around where someone proposed getting a bunch of rocket pointing downwards. And then if the Russians send some nukes, you set off all the rockets, and it will increase the rotation of the Earth so the rockets would miss. And the idea went through upper command, was signed off by generals, all before someone was like, a) this wouldn't work, and b) if it did work it would kill us all.

Just imagine the tidal waves if nothing else! There was someone who was suggesting we nuke the Moon at one point, as I recall. There goes DTN [laughs].

Not to be too negative, but so Oppenheimer had that kind of that realization with nuclear weapons, 'whoops, I've done this terrible thing.' The Internet, I would personally say is more good than bad, but there's still a lot of bad. For you, is there any kind of Oppenheimer moment or is that too harsh?

It is harsh. But the realization that there's so much negativity on the Internet, all the horrible things are taking place. I don't have to list them all, it is very worrisome.

That was the reason that I wrote that op-ed piece. And the only solution I'm coming up with is that stakeholders where everybody gets involved.

This can go in one or two directions, it can get a lot worse. And yet the value to humanity has been so great. Look at us, we can communicate.

But it is a concern, my journalist daughter Lynn Hirschberg. In her field, the abuses to journalists are huge. Plagiarism, the stealing, the lack of credit. It's destroyed that business quite a bit. Not only the fact that people read news online instead of buying the paper, but the journalists steal from each other without accreditation, or compensation, or anything. That's an internal issue, of which the public's not very aware of.

But Spotify is another example with the music industry.

And by the way, some of the blockchain and some of the cryptocurrency attempts are trying to fight that, where people can donate to the artists in small amounts easily, which could make a difference to the artists' livelihood. Journalists as well. So there's some possibility of some relief in that direction.

For me, I found with journalism that it's like is when the asteroid wiped out the dinosaurs - that little creatures that crawled down the hole survived. For me, it's about finding a little niche in journalism. There's like five data center journalists out there, so we know the one that copies.

On the Oppenheimer comparison, I guess the other difference was that was building a bomb that could potentially set all of the oxygen in the world on fire. Whereas you guys were just trying to connect people and connect researchers. It's a much more noble idea and hope.

Here's a great novel. Go back to the days of creating the Internet, and let the designers be aware of the consequences. Imagine all directions that story could go in.

Putting that to you then. If I got out of a time machine, once you got over the fact that time travel exists, how do you think you'd have reacted?

Well, we could have put some safeguards in back then to protect, but not prevent all the abuses.

We could have put in security controls. There are at least two things we should have done, but we didn't for reasons I'll explain. We should have put in strong file authentication. So when I send you a file, there's assurance that what I sent you is what you got unaltered. Also strong user authentication, that it really is you I'm talking to him, not some artifact or some avatar, I'm talking to him.

That would not have been hard. And had we put it in, we should have turned it off immediately. Because our task then was to get readership, get people involved. And it was very difficult by the way. At every stage, nobody wanted to put their computers on the network, nobody wanted to join a network. It was too hard, until they could test it.

So we had to make it very easy. And then as the abuses started, we could have cranked those things up to a certain level.

But could we have prevented the gossip chambers, the blaming, the malicious behavior with safeguards? It's not clear, even at this stage what we could have done.

The whole issue of anonymity is a very interesting one. Because, what does the Internet do? It allows anybody, no matter how poor, or ugly, or fat, or eating bananas and throwing potato chips all over the floor, with a computer and Internet access to reach millions of people, at no cost and time or effort or money, instantly and anonymously.

Well, that's a perfect formula for what we have today.

And now should we have made it not anonymous? There's a whole set of issues there that are perhaps best dealt with by the ethicists. But we as engineers can't ignore that. And we don't think about that ordinarily.

But had you presented that to us in those early days, we probably would have been inadequate in making the right judgments. And the right thing to have done would have been to bring in the people who understand these consequences, which we did not address at all in those days. So I think it's a very interesting study, and it'd make a great series of novels.

Another thing was, when you went to AT&T with the idea of transmitting packets on their network and they said 'I don't think this is a good idea. I can't see any application.' Do you think there are other things now that you're working on, or people in your lab are working on, that have a similar reaction but could be just as big down the line?

Well two things. First of all, they said it wouldn't work. They also said, even if it does, we want nothing to do with it. Why did they say that? They had a good reason. There was no data traffic. It was all voice traffic, and were making a lot of money. And they couldn't see beyond that stage.

So short term was the right answer. Long term it was a disaster.

But what am I working on now that maybe needs to be reevaluated? Well, things like blockchain, have that kind of very strong negative, or positive reaction. And unfortunately, most people don't understand the implications, the dangers.

I was just reading a prospectus someone sent to me about a fund they want to create where people can invest in this whole cryptocurrency world. And they explained the positives and weakly present the negatives in the end, and the risks and all the rest. So they're hyping it, they make it look good. People will invest. And if bad things happen, there'll be another Madoff kind of thing, a collapse. So that's one example of an area where people are strongly rejecting potentially serious consequences.

And you know, governments are involved in this right now, obviously, for different reasons. But the thing is, you got the whole banking industry taking the position, which is not an objective motivation.

It's almost like crypto has become a distributed Madoff. There's not really one guy. Everyone is Ponzieing each other to pump this thing higher. Again, it's an interesting thought experiment, just a shame we're the ones being experimented on.

And yet, the whole issue of inflation and collapsing currencies is driving the move toward acquiring these currencies which have no intrinsic value, but just have a scarcity value at this point. But some of them are trying to provide true value. There are over 9,000 cryptocurrencies right now. Many of them shams, and many with really good motivations, but yet to be seen. That's why I'm interested in it, there's a lot of interesting problems.

And yeah, when you have 9,000, even trying to root through them and analyze them must be incredibly time intensive.

A lot of them are less than a millionth of a penny per share. But some of them are up there.