As Russian forces move deeper into Ukraine, leaving destruction and death in their wake, the focus has naturally been on the impact on the physical world.

But there is another territorial land grab underway in a different realm, cyberspace, that could also have a profound impact on the sovereignty of a people.

The war has seen Ukrainian government, bank, and media websites taken offline, and parts of the country disconnected from the Internet - either intentionally, or due to power cuts.

However, the current chaos of an ongoing conflict makes it hard to separate misinformation, accidents, and temporary measures from deeper, long-term plans for Ukrainian connectivity.

To understand what may yet come, we can look to two Ukrainian territories that were already under unofficial Russian control: Crimea and parts of Eastern Ukraine.

The Kerch cable, Crimea, and the rise of Miranda Media

In 2014, the Russian government laid claim to Crimea, a peninsula to the south of Ukraine.

Prior to the seizure, Crimean Internet took place over Ukrainian networks and laws. From March 2014, however, that changed - with the territory falling under Russian Internet regulations.

The new government soon began building the infrastructure required to remove Crimea from Ukraine, but the process was slow as the poor region was heavily reliant on the Ukrainian mainland for supplies and connectivity.

"Russian control of Crimean information infrastructure followed a 'soft substitution' model and took about three years," researchers at the IIJ Research Lab, Citizen Lab, and RIPE NCC found in a 2020 paper.

In 2014, several major events happened. First, Ukrainian telecommunications companies began to leave the region - some by choice (MTS Ukraine selling its assets), and others forcefully, like Ukrtelecom (when armed guards stopped the telco's staff from entering their offices and facilities). In the latter case, Russian-backed Krymtelekom took over the operations.

Second, direct links to the Ukrainian mainland began to be sabotaged - although the majority remained.

Third, Russian state-owned telecommunications company Rostelecom quickly deployed a 110Gbps submarine link from Russia to Crimea, the Kerch Strait Cable, at a cost of $11-25m. Services were offered by Rostelecom's newly-created local agent Miranda Media.

With such a small bandwidth, it meant slower speeds for Crimean citizens. Players of the popular video game World of Tanks complained about the increased latency, while everyone had to shoulder higher Internet costs.

It took until 2017 for Russia to deploy a better cable along the same route. Throughout, Crimea was slowly centralizing its Internet routing and moving as much data via Russia as possible, again degrading performance.

But it still relied on Ukraine for a lot of connectivity. That year, Ukraine's then-president Petro Poroshenko announced his country would block Russian sites like Yandex and Mail.ru. Soon after, Crimeans were complaining that they could not access the websites, highlighting that they were still connected to Ukraine.

"The summer of 2017 is marked by a big wave of pressure on Ukrainian ISPs and Ukraine stopping to provide traffic to Crimea (allegedly on July 12th, 2017)," the IIJ Research Lab et al. report notes.

The researchers tried to track the topological changes in Crimea following the invasion. To explain what they found, first we must understand Autonomous System Numbers (ASNs).

Essentially, an autonomous system (AS) is a collection of connected Internet Protocol (IP) routing prefixes that network operators control, which defines routing policy to the Internet.

Evey AS is given an ASN for use in Border Gateway Protocol (BGP) routing. ASNs are required by network operators to control routing within their networks and to exchange routing information with other Internet Service Providers.

That sounds complex, but the end result is simple: Control over the autonomous system allows network operators to decide the route data should take - for example across the Ukrainian mainland, or into Russia.

Before the takeover, Crimean ISPs served as proxies to larger Ukrainian and international ISPs, simply shifting data in their direction. “2014 is marked by a significant dependency increase for a new AS, Miranda Media, and its parent company, Rostelecom. At that time, numerous AS paths feature the same pattern, the paths originate from Crimea go through Miranda Media and then Rostelecom,” the study found

This routing change significantly reduced the number of paths transiting through Ukraine every year until mid-2017, “where we see no more path going through Ukrainian ASes.”

The Donbas disconnect

Eastern Ukraine is more complex, both politically, and technologically. Up until this most recent invasion, the territory was controlled by Russian-backed separatists, with Russia never admitting that it had any control over what happened in the region.

It also has an unusual network topology, a remnant of the chaotic days after the fall of the Soviet Union.

“The whole post-Soviet world is probably the most complex topology on Earth,” University of Paris-8 associate professor Kevin Limonier told DCD. “This is because the network developed in kind of an anarchic way in the ‘90s, with no state authority, no planification of any kind. Even in the US, the planification was stronger than it was in Ukraine and in Russia.”

This is partially down to the collapse of state authority during the ‘90s, and a simple matter of size. Small Internet Service Providers sprung up across the two nations, connecting remote cities, each of which needed ASes.

“So you have this kind of bottom-up movement that happened in the ‘90s, with thousands of local ISPs routing these small cities - for example, it's very normal in Russia to have an ISP just for a city of 50,000 inhabitants,” Limonier said. As of 2015, there were 15,433 ISPs registered with the Russian accounting chamber.

With Crimea a poorer and less developed region with a limited terrestrial border, that meant the "simplicity of the local Internet topology made it an ideal" candidate to research, Limonier and co-author Louis Pétiniaud (et al.) said in a study published last year.

But "the situation of Donetsk and Luhansk Peoples’ Republics is different. First, its geographical situation differs from the easily circumscribed Crimean Peninsula: the Ukrainian and Russian mainland infrastructures are numerous and hard to easily map. Second, the geopolitical status of Donbas is much more hybrid than Crimea’s," the researchers note, as part of work for the university’s Geopolitics of the Datasphere (GEODE) research center.

With the separatist governments of Donetsk and Luhansk, sanctions from Kyiv, and behind-the-scenes actions from Moscow all involved in controlling ASes, assigning intention to what happened to networks in the region is also difficult.

“So you have all of these interactions that produce situations of dependencies across the network, but that are really driven by a variety of actors that actually do not talk to each other,” Louis Pétiniaud told DCD.

Still, it was clear to the researchers what happened in the years following the takeover: “What we've seen, and what we are seeing, is that there is no more direct connectivity between Donbas and Ukraine,” Pétiniaud explained, with ASes routing around the border.

There are several known backbones that directly link Ukraine and Russia, but data transfers between them have dropped sharply since 2014 - not just in the separatist-controlled regions.

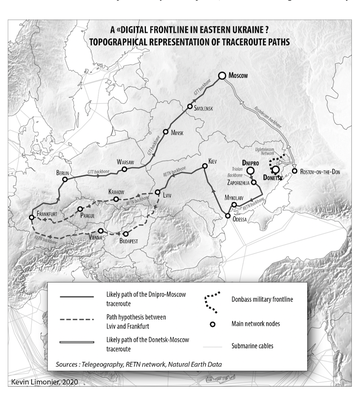

The group sent traceroutes from Dnipro (an eastern city that at the time was firmly under Ukrainian control, but is now being bombed) destined for Russia. It did not cross the Donbas military frontline - despite it being the lowest latency route.

Instead, it traveled down to Odessa, back up to Kyiv, west to Lviv, and likely across Poland and the Czech Republic, before reaching Frankfurt, Germany (home to the DE-CIX Internet exchange).

Once there, it wended its way back east along a GTT backbone, first through Berlin, then Warsaw (Poland), Minsk (Belarus), Smolensk (Russia), and finally Moscow. Again, this is not a logical route if geopolitical concerns had not intervened - the whole trip took 78 milliseconds across 11 hops.

A similar ping from the nearby, but separatist-controlled, Donetsk immediately went east into Russia, likely along a Rostelecom backbone, and directly into Moscow. That took just 13 milliseconds across three hops.

"What we've been seeing in Eastern Ukraine is that you have territorial appropriation by Russia, through connectivity, basically," Pétiniaud said.

Due to the inability to confirm that this was intentional, Limonier was cautious: "We cannot say that routing protocols, and especially the BGP layer, became a battlefield like a territory is a battlefield. But something is definitely happening."

How cyberspace overlays with physical space

The researchers are "trying to understand how Internet routes, infrastructure, and topology is consistent with geopolitics," he said.

This is difficult, because traceroutes are not always the same - ideally, one should do thousands over several days to see if the data journey substantially changes.

Limonier and Pétiniaud are building out more tools to improve the accuracy of their work, and plan to travel to Kyrgyzstan to see if they can match up what they see with RIPE Atlas probes with what's on the ground.

But even as they improve the methodology and accuracy, there is a fundamental difficulty in getting people to pay attention to a transdisciplinary project.

"The reaction [to our work] is very interesting because the people who are capable of understanding the technicality of what we are doing often do not understand the political or geopolitical value of what we're doing," Limonier explained.

"We are working with mathematicians, with computer scientists, and we are geographers and geopoliticians. So we had to invent a common language."

He added: "We have an opportunity to work together because there is a whole field opening - for exploring, understanding, and mapping cyberspace in a geopolitical perspective, crossing it with history, anthropology, sociology, geography, etc."

For the people of Ukraine, such work may seem distant, and it certainly will not help them during the current invasion.

But should things shift to a more permanent territorial takeover, it is critical to understand what that means for the occupied peoples’ access to the Internet.

From a simple consumer standpoint, data routed through Russia will mean slower connectivity and likely higher costs - which is frustrating for individuals, and damaging for businesses. Companies that stored data in the West will be forced to shift it east.

More profoundly, it also means that the data will fall under the purview of RuNet, the Russian-controlled section of the wider Internet. This will entail user surveillance and data capture, and vast censorship.

While not as advanced as China's Great Firewall (even though Russia uses some of China's technology), RuNet blocks many news outlets or places of free expression. The country's control strategy tends “to be more subtle and sophisticated and designed to shape and affect when and how information [was] received by users, rather than denying access outright," researchers Ronald Deibert and Rafal Rohozinski found in 2010.

In 2014, the Russian parliament passed a law that required Internet companies to store the personal data of Russian users inside the country's borders, giving companies until 2016 - although in reality, it took a little longer for this to be technically possible due to a limited data center footprint within the country.

In late 2018, the country took things further, forcing ISPs to install deep packet inspection equipment on company networks. This makes it easier to block access to apps like Telegram, or throttle Twitter - although the rollout of DPI is still ongoing, making such bans imperfect.

The country is also developing its own alternative to the Domain Name System (DNS), the naming database in which Internet domain names are located and translated into Internet Protocol - although, again work seems slow.

The government additionally claims to be developing the ability to isolate Russia from the wider Internet.

Russia said that it would test Internet isolation technology in April and October 2019, but neither event happened. In November that year, Russian telecoms companies said that limited tests of the Internet-isolation equipment caused slowdowns and service disruptions.

But work is ongoing. Internet regulator Roskomnadzor has been tasked with creating a registry of Internet Exchange Points, communications lines crossing state borders, and ASNs responsible for the stable operation of the RuNet.

Only a few outside researchers appear to have been watching what happened in Crimea and Donbas, but Russia is studying the crossover of geography and cyberspace intently.

"We have some contacts with Russian counterparts," Limonier said. "There is a center in Moscow University that is doing similar work - but on the side of the Russian government. There is this researcher that I have spoken to several times, and he's clearly investigating BGP routing to try to make it consistent with the geopolitical borders of the Russian Federation.

“There is an imperative of control, that's how they are seeing it. They know what we do... but the purpose is a little different."