Every time web traffic suddenly drops in a particular country, an alert goes off in Cloudflare’s headquarters in California.

“It could be that there's something wrong with one of our points of presence, or that something’s wrong with the connectivity,” John Graham-Cumming, the web infrastructure company’s CTO, told DCD. “Our first reaction is ‘did we break something?’ And we want to be able to fix it.”

The alert is repeating again and again, but there’s nothing Cloudflare can do. The outages are real, but nothing is broken - it’s an intentional disconnection. “We actually have an internal chat room called Internet Shutdown Tracking, because we see these things happening pretty regularly.”

One moment a country is part of the Internet, a piece of the whole. The next, darkness, a nation winking out of digital existence, unmoored and alone.

“The thing to note about state-sponsored cut-offs of the Internet is how widespread they are,” Graham-Cumming said. “Even this year, there’s been Venezuela, Sudan, Indonesia, Sri Lanka, and Ethiopia, to name but a few. The Democratic Republic of Congo shut down the Internet completely for 20 days - it's a long list of shutdowns, and some of them are quite large.”

Authoritarian regimes are the most common abusers of this power, forcing telecommunications companies, which are often state-owned, to shut down operations. But it is in a young democracy that the worst offender is found.

This feature appeared on the cover of the November issue of DCD Magazine. Subscribe for free today.

India's shutdowns

“There’s been quite a lot of advocacy around some of the shutdowns that happened in Africa, which were largely on a national level and executed by central authorities,” censorship and connectivity researcher Jan Rydzak told DCD.

“There were surprisingly few people focusing on the number one country in which the most shutdowns were taking place: India. Since 2012, the country has had approximately 350 cases of shutdowns of various kinds at various levels. This is just orders of magnitude more than any other country in the world.”

That count, ever-growing, has been carefully tallied by the Software Freedom Law Center, India, which began tracking the outages in lieu of any official announcements.

“In 2012, we started noticing - in addition to website and content blocking - complete blanket shutdowns of the net in certain areas,” Mishi Choudhary, ‘SFLC.in’ founder and human rights lawyer, said. “It started with around three shutdowns. By 2014, it was still in the single digits. Then in 2015, we saw a spike in the number of instances to around 14.

“Last year, we had the highest numbers we've ever seen - 134.”

Choudhary’s figures are on the conservative side, she noted. Only outages that the center can confirm as intentional are included, with media reports and tips used as a starting point, backed up by SFLC’s legal challenges to individual states, demanding information.

India’s federal government has a long process for deciding whether to initiate a shutdown, with checks and balances in place, but the country’s 28 states are not bound by the stipulations of the Information Technology Act. “What the states started doing is use the Police Power, a very different statute,” Choudhary said.

In cases of civil unrest, police in mostly northern and western states are turning to shutdowns to try to defuse the situation. “It can become a checklist for the police when they do their job: They think ‘first shut the Internet down, that will stop this viral spread of messaging, and then go and control the situation on the ground.’”

This approach can be tempting for those in power, Choudhary admitted. “India has a long history of communal riots exacerbated by our colonial masters. Social media has really amplified the messaging and aggravated the situation, and made it very, very easy for a large group of people to be able to receive messages and assemble in one place.

“As much as I am a free speech advocate, as much as I love the Internet, I am not blind to the fact that if a police commissioner or magistrate who thinks there are going to be 2,000 people [converging] that want to kill each other because of some WhatsApp message, they may want to shut it down.”

The problem is there’s no data to confirm that shutting down the network actually helps law enforcement agencies do their job, or stops the messaging, Choudhary said. “It's not that the riots didn't happen before these tools were there. People use phones, there was word of mouth, people live in areas together, there are ghettos. There's a lot that goes on in a riot.”

Working at Stanford’s Global Digital Policy Incubator, Rydzak has tried to analyze whether the shutdowns were actually effective. His paper ‘Of Blackouts and Bandhs: The Strategy and Structure of Disconnected Protest’ took SLFC’s Indian outage data, as well as datasets on protests (their location, length, who was involved, and whether it was violent), to see how the shutdowns changed their nature.

“Essentially, I was trying to look at whether the protesters’ strategy changes with a lack of access to information and communication,” he said. “In an information vacuum, does information travel differently, and does it lead to different outcomes for protests?”

In non-violent protests, the results proved “very ambiguous and inconsistent,” Rydzak said. “Shutdowns are sometimes effective against peaceful demonstrations, but it's by no means guaranteed. It's practically no different from a coin toss.”

It was in violent protests that Rydzak saw a real difference. “Shutdowns are followed by an escalation in violent protests. It's a very strong effect that doesn't just refer to the first day that a riot takes place, but to several subsequent days as well.

“People will always find a conduit for protest. Social media is just a platform for people to vent their frustration and anger. This is just a hypothesis, but it's possible that anger that is normally spilled out on social media can spill out into the streets instead.”

The siege on Kashmir

The majority of intentional outages last up to 72 hours, short disruptions across a state, or sometimes a smaller area. Other times the blackout is widespread, long-lasting and total. Rydzak calls these events Digital Sieges.

“What's happening in Kashmir is absolutely a siege. It's just unprecedented. Landlines are not usually affected. But in this case, the government decided to take no risks and just cut off all communication completely. It's a siege in every sense of the word; not only a militarized siege, but also a siege of all forms of communication. You'd be hard-pressed to find an equally extreme example even among the hundreds of shutdowns that we've seen so far.”

The longest shutdown ever recorded happened in the state of Jammu and Kashmir in 2016, lasting 133 days. Now, in October, the state is offline again, but this time it’s different. “This is the first time that phones were completely shut down - landlines, mobiles and Internet - everything,” Dr. Mudasir Firdosi, a Kashmiri psychiatrist and writer based in London, told DCD.

In Jammu and Kashmir - a troubled state with high levels of unrest, an insurgency movement, and regular terrorist attacks - darkness has prevailed since August 4th. “Even in the modern world today, it is possible to isolate a large population of eight million people and not let them talk,” Choudhary said. “Again, there are national security reasons for it, we can’t deny them - but it has a real impact.”

72 days into the siege, a small opening was allowed. On October 15, phone calls from ‘postpaid’ contract cell phones were let through, while calls from the more commonly used top-up phones remain blocked. “I believe the reason for that is when you take a postpaid connection in Kashmir, they verify your identity, they know who you are,” Firdosi said.

With limited connection resumed, the Kashmiri diaspora is finally able to connect with loved ones in the state. In some cases, the news has been dire - relatives have learned of illnesses or deaths; funerals have been missed, weddings delayed.

“This has got so many costs,” Firdosi said. “We are living in the Internet age, students are sitting at home, people have to fill in forms for jobs or for higher education. Businesses are run on the Internet. Everything is down.”

“People at some places didn’t get immediate medical help, resulting in deaths and aggravation of terminal illnesses,” Aakash Hassan, Kashmir correspondent at CNN-News18, told DCD.

For journalists such as Hassan, the situation is fraught with danger. “There have been multiple cases of journalists being detained and even injured while covering stories. One photojournalist was injured with pellets - this is the physical aspect,” he said.

“[But the] intangibility of this clampdown has affected reporters the most, because they are the ones who have to write about it and get news out… We have been provided a facilitation center by the administration where we can use the Internet for around half-an-hour in 24 hours. Each day, we bring our stories and have to wait in line to file. There has never been a time when journalists were so disempowered.”

Fear prevails. No one knows who could be listening. Firdosi recalled conversations with doctors in Kashmir who were granted limited mobile access: “When I start asking them how the situation is, they just start saying, ‘oh, the weather is good.’ They don’t talk about it. People are afraid.”

The distress is not limited to the region. Firdosi and colleagues are studying the impact of the disconnection on Kashmiris living abroad. “We have a survey with around 450 responses,” he said. “Though we can’t diagnose people on surveys, it just gives an indication, but 88 percent showed abnormal scores pointing to cases of depression or anxiety.”

Using the ‘Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale,’ more than 90 percent scored high on the ‘frightened feeling as if something bad is about to happen’ section of the survey. “It’s the not knowing,” Firdosi said. “It has taken over our lives - I am at work right now, and I am still thinking about it.”

So far, these outages have primarily impacted less influential areas. “If something were to happen in Delhi, Bombay, or Calcutta, the noise would be heard and ricochet all around the world,” Choudhary said.

This is partly because they are seats of power, globally recognized regions deeply integrated with the wider world. It may also be because these are areas with higher levels of Internet penetration, where a shutdown would have a far more profound impact.

“One of the things which we've always struggled with is that, because of the Digital India initiative, so many of the services are now going online,” Choudhary said. “I'm supposed to pay my taxes online, I'm supposed to keep all my important documents with the government online; after demonetization, we’re expected to go cashless completely. Almost my entire life is going to be online.

“And then I'm handing over the power of that kill switch to these police guys who have not even thought about these things in a nuanced way. And, unfortunately, constitutional rights and laws mean nothing to them.”

Hong Kong on the brink

We may soon find out what a shutdown of a highly-connected global financial center could look like. Over in Hong Kong, the threat of disconnection is growing. On October 4, Hong Kong chief executive Carrie Lam enacted the colonial-era Emergency Regulations Ordinance, which allows the government to “make any regulations whatsoever” that it considers to be in the “public interest,” if faced with “an occasion of emergency or public danger.” This would include communications shutdowns.

“The use of the Internet for both the [2014] Umbrella Protests and the current protests is vital,” Nathan Law, Hong Kong politician and activist, told DCD.

“In terms of the current protest, we use online platforms to generate ideas, making our protest more fluid and more influential. Using the Internet can also make us better at reaching the international community. The protester can participate in the agenda… broadcasting our message rather than letting the media interpret everything.”

Law, founding chair of the Hong Kong youth activist group Demosistō, said the movement already assumes it could be under digital surveillance: “We don’t talk about sensitive issues through social networks or online communication software. If we have to do so, we will use a more secure app like Signal.”

Protesters are also “preparing for the possible shutdown of the Internet,” Law said. For instance, they have apps that don’t need the Internet to work, like FireChat, which uses wireless mesh networking to enable smartphones to communicate directly. But being taken offline would still stymie the movement, he admitted.

“It is important that we retain a free flow of information and a channel to reach the world,” he said. “If you take a look at the situation in China, it is like a black box, it is difficult for the activists to be connected and for the outside world to understand what is happening inside. So it is very important for us to remain open.”

Others in Hong Kong are concerned, including members of the business community. In August, as rumors of impending digital censorship spread, the Hong Kong Internet Service Providers Association sent out an urgent statement: “Technically speaking, given the complexity of the modern Internet, including technologies like VPN, cloud and cryptography, it is impossible to effectively and meaningfully block any services, unless we put the whole Internet of Hong Kong behind [a] large scale surveillance firewall.

“Therefore, any such restrictions, however slight originally, would start the end of the open Internet of Hong Kong, and would immediately and permanently deter international businesses from positing their businesses and investments in Hong Kong.”

The association added: “Hong Kong is the largest core node of Asia’s optical fiber network and hosts the biggest Internet exchange in the region, and it is now home to 100+ data centers operated by local and international companies, and it transits 80 percent+ of traffic for mainland China. All these successes rely on the openness of Hong Kong’s network.”

A Chinese approach to the Internet would mark a radical shift for Hong Kong, which - at the time of publication - has a relatively free and open network. “China is the prime example of a preventive regime,” Rydzak said.

“Instead of reacting to protests, they try to smother them in advance. They are operating under the assumption that criticism and protest born on the Internet can spill over into the streets, so nipping it in the bud is their priority.”

A web of its own

China’s Internet is unlike anything else. “The sophistication of the infrastructure and the censorship system in China is much more superior to anything that we've seen,” Professor Christopher Leberknight, online censorship researcher at Montclair State University, told DCD.

“China has gotten it down to ‘we can block specific keywords, we can block specific pages of a website.’ They also have a huge army of people that are just looking at blogs, websites, and if there's something that's a little bit ambiguous, then the information doesn't get posted. It sits in limbo for 24 hours.

“And then there are individuals that actually read the content and make the decision as to whether or not to publish it."

Circumvention tools in the country are hard to use, because “in China, you can't use encryption-based technologies unless you register with the authorities. If you try to transmit unregistered encryption-based data, the packets just get dropped,” Leberknight said.

Beyond the software and man-power required to run the Great Firewall, the nation - with the fervor of a technocratic regime - made sure its Internet was built in its image.

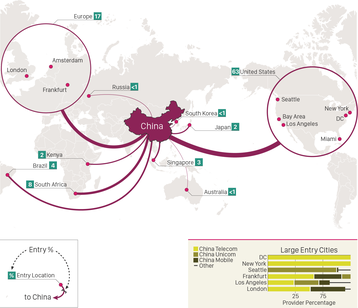

"Most developed nations have a large number of non-domestic carriers with a presence in-country. This means that foreign telecoms are interconnected with local and other international carriers at physical locations (Internet Exchanges) within these countries," Dave Allen, Oracle's VP of business operations and strategy, said in a research report.

"China is different: there are no observable foreign carriers with a presence in China’s borders. The general trend globally is that countries - both developed and developing - are becoming increasingly connected. China, on the other hand, has had no meaningful foreign telecom presence over our many years of historical data.

"Nevertheless, we know Chinese citizens can still connect with the global public Internet, subject to the restrictions placed on them by the Great Firewall. China’s connections to the rest of the global Internet just aren’t in China. They are in Western Europe and the United States, along with a few other locations."

This offers a crucial advantage for a censorial regime, Mohit Lad, CEO of network monitoring company ThousandEyes, told DCD: “If you can concentrate all your traffic to a certain set of points, then you can technically have the ability to inspect every single packet that goes through there and be able to apply rules and so on.

“The interesting part about China is they built it very early in the Internet's rise. And as a result they've built it, they've scaled it, they've tuned it. And they are able to handle the kind of volume that they see through their firewall at scale.”

Other states are envious, but may struggle to achieve the same level of control over their network, Lad said. “If you think about countries like Russia, it's going to be pretty challenging, because it's at a scale where you can't just turn it on; it's a very different problem.”

But that doesn’t mean they're not trying.

Building Runet

“There are a lot of small ISPs [in Russia] who have this transitional traffic flow, and these lines are still working,” Ilona Stadnik, a cyber security researcher at Saint Petersburg State University, told DCD.

“[Most] Russian traffic still goes inside the territory and just one percent goes out, but these lines are still working,” Stadnik said. “And if you issue an order that now just one state network operator, Rostelecom, will be able to move traffic abroad, it won't work - the authority would have to go and dig out all the lines that are going outside Russia. It will take time, and it's not feasible.”

That may change, however, with incoming laws that impose strict demands on network operators that “are so high that they will probably be deprived of their business, and will have to sell it because the expenses will be too high,” Stadnik said. “This could lead to the absorption of small ISPs and network operators by the biggest one. So the number of independent, unknown transborder lines will be reduced.”

Stadnik could not say whether this was an intentional result of Russian policy or a side effect, but the outcome is clear: “Just change the market itself, and then it will be easier to control.”

Russia has also - perhaps more aggressively than any other state - sought to shut down the Internet of other nations. The country is linked to numerous distributed denial-of-service attacks on foreign territories, although attribution can always be tricky.

Bringing down your enemies

“You've got a situation where outages are technopolitical,” Martin Rudd, CTO of cyber security and government infrastructure company Telesoft, told DCD. ”You can use an outage to enforce an aim, whether the goal is espionage, sabotage or theft. You can use that outage against either that nation-state or against a multinational competitor or multinational organization.”

In 2007, following the removal of a statue of a Soviet soldier, a series of coordinated DDoS attacks battered the tiny Baltic state of Estonia. The attacks grew in intensity, hitting government, banking, and media sites, among others, and threatened to bring the nation to a standstill.

“Basically we closed off Estonia from abroad, the Internet became an intranet in Estonia. We could still operate it, except that there were no [outside] connections - you don't see CNN or BBC or whatever you need to use, but you can still use the services inside,” Cybernetica CEO Oliver Väärtnõu told DCD.

Väärntõu’s company, best known for developing Estonia’s ‘X-Road’ network layer and the Internet voting system that has allowed Estonia to become a highly advanced digital nation, is all too aware that attacks by nation-states could happen again.

“When the 2007 cyber attacks happened, it was kind of like ‘this is the real deal.’ So we looked at how we can actually get over this, what are our vulnerabilities, etc. It’s about not only creating systems using the secure software development process, but also how you develop and refine the architecture of the e-government.”

The country is actively preparing for the worst. In 2017, Estonia announced plans to build a data center in Luxembourg to store crucial government and citizen data as a backup. More data centers in different countries were planned, Väärtnõu said, but the process has been slow.

“Today, we are not fully in this position where we can say that if Estonia is completely shut down, then the government will continue in cyberspace after being taken over. It is a very fancy thing to say that our government is backed up to Luxembourg, or in the future to whatever country it is - but we also have to bear in mind that when we create the infrastructure inside that country that it's fully resilient, that we have the failovers, and that everything is being copied.”

The idea of a digital nation unencumbered by the threat of physical attack remains a dream. The nightmare of an attack on sovereign soil is still a terrifying possibility. And, despite Estonia and Cybernetica’s efforts to improve cyber security, there’s little one can do against certain events. “If there is no electricity, I think then we're going back to the Stone Age,” Väärntõu said.

Taking out a larger nation may prove trickier. "I'm not of the belief that one single attack could take down America's Internet at all," Winn Schwartau, the cyber security researcher who in 1991 warned Congress of the threat of an 'Electronic Pearl Harbor,' told DCD.

“You'd have to cut too damn many wires.”

Motivated by nothing more than their business interests, companies in the US have helped strengthen the Internet, pushing for resiliency, backups and redundant connections.

It’s also not clear if an adversary would want to take America out. “It's much more profitable to keep it going, because of social media and the access it gives you,” Mark Carney, pentester and security researcher for Security Research Labs, said.

“So motivated and intelligent attackers think ‘okay, there is now such redundancy that we can't bring it down, however, there's such connectivity that we can influence that in a way where we can have an effect.’”

Russia, meanwhile, maintains that it too could face attacks on it own network. In April, the country passed the controversial ‘Internet isolation’ bill “providing for the safe and sustainable functioning” of Russia’s Internet, that by November is meant to allow the state the ability to cut itself off from the wider web.

“We should be afraid of [an] external kill switch - this is how it is explained to us,” Stadnik said. “This is a unique discourse that the Russian authorities have, nobody in the world is really talking about an external shutdown. This is a story that can be really kind of favorable for other countries to pull.”

Many are concerned that the law has more to do with Russia controlling its own territory than any real fear of foreign attacks. “This August, there were documented shutdowns of the mobile Internet during the protest in Moscow. I think they are trying to test how far they can go with this, and to what extent they can execute this, and to see how people react to it.

“The trend is obvious,” Stadnik said. “The government really wants to keep track of what's happening in the information sphere, what's inside the traffic. But the only problem is that the amount of such data is so enormous that even if you pass this regulation, you won't find enough equipment to do so.”

Unable to build the tech on its own, Russia appears to be turning to China for help, with a number of technological agreements signed over the past three years. This October, the two nations signed a joint treaty aimed at tackling “illegal Internet content,” which lacked specifics, but might include China sharing some of its Great Firewall hardware and software.

As for Russia’s Internet isolation law, it’s light on technical detail, partly for security reasons, and partly because "our legislators don't know in detail how everything works, because for them the Internet is more like a telephone," Stadnik said.

"You have people in the legislative bodies that don't have enough technical expertise to make such laws. And they are sometimes very wrong, sometimes very illogical. But it doesn't prevent legislators from moving them forward. That's how it works in Russia."

Key aspects of the law remain shrouded in mystery, but the country is barreling ahead nonetheless. In September, Alexander Zharov, head of the federal communications regulator Roskomnadzor, said that “equipment is being installed on the networks of major telecom operators” to allow RuNet to be separated from the greater Internet.

"Countries are always threatening to cut themselves off," Professor Milton Mueller, author of Will the Internet Fragment? and one of the founders of the Internet Governance Project, told DCD.

"But when you look more closely at those proposals, they really are not about cutting themselves off from the Internet. Other than in emergency situations, that's really pretty stupid and self-destructive.”

Instead of a complete separation of a nation’s Internet, “the number one fear for me would be the Balkanization of the Internet,” Schwartau said.

Mueller agreed: “Countries are trying to align national boundaries with their digital economies as much as they can. That's kind of pushing the stone uphill, because it's just not the way the Internet is constructed. What's interesting now is that it's gone beyond the network layer into equipment and software, where we're discovering how damaging that decoupling and that disintegration will be.”

Great powers diverge

He fears what the deteriorating relationship between China and the US will do to the Internet. “There was hope that China would gradually become aware of the degree to which their power and their wealth relies on openness, interconnection, and trade with the rest of the world,” Mueller said.

“And they couldn't play the game both ways: they can't shield themselves from foreigners, and at the same time expect foreigners to be open to them.”

But, while he conceded “there was some need for a confrontation or systemic change in the way [China does] things,” Mueller believes that “President Trump went about it in a very, very terrible way.”

Tariffs, sanctions on globally-focused companies, and restrictions on trade in technology will only make the divide worse, he argued. “What the US is doing is using our dominance of chips to shut the Chinese out of high technology, because they have this nostalgic sense that the technological and economic dominance that the US enjoyed after the decline of the Soviet Union is going to last forever.

“And they think that they can stunt China's growth and keep it subordinate indefinitely by cutting them off from US technology. All that's going to do is make China develop its own chips and its own advanced services in a way that is not integrated with the West. I would much rather have China buying US chips and having technology flowing both ways, than to have these fragmented blocks around these technological superpowers.”

The idea of a sovereign digital state in charge of all the bytes within its borders is growing in popularity, with data residency laws spreading across the globe. "What we're seeing is that all those data centers around the world are becoming sovereign assets,” Telesoft’s Rudd said.

“The boundaries in cyber are so blurred, stuff like banking, finance and the stock market - are they part of the sovereign state, while being commercially owned?”

For the normal day-to-day operation of the Internet, which country a data center resides in is mostly irrelevant. Latency, grid infrastructure, and cooling costs are all important, but an average user in the UK will not notice a difference between a facility in Denmark or Belgium, for example.

However, when things become strained, the location of data can be crucial. Imagine a scenario where hackers attack a “national telecoms operator in a particular country that is using a cloud provider,” Rudd said. “Do you really want the data [on the attack] which is being brought up from that network to be classified by a third party in another country?

“That's the same data which is used to optimally train the AI algorithms in defense for anomaly detection or machine learning. It tells you who is attacking what and how.”

Conversely, if nations require data to be stored in a country of origin, information on how an attack happened may be withheld from a multinational business. Suddenly, it is unable to fully study the intrusion attempts it has suffered in certain regions, and is less secure as a result.

We don’t know how this will play out; it is not clear how much further the Internet will Balkanize. In a world where authoritarianism is on the rise and democracies are weakening, the future appears bleak.

“I think the norms and the levels of cooperation that are happening across North America and Europe are going to move towards a more integrated system,” Mueller said. “And then we're seeing the rest of the world, the more authoritarian world, detaching from that and possibly creating a bipolar information technology world.”

The West, to be clear, is not without sin. It exports the tools of surveillance and censorship and is experimenting with small shutdowns of its own, on San Francisco’s BART network and the London Underground. It also surveils its people, and blocks certain websites.

“It is very difficult for the Western world to complain about things at this point, because we're putting so much pressure on the social media companies to censor things,” Mueller said. “So what basis do we have to say that China should have this freewheeling open social media environment?

“And what happens immediately is that they pick up on that and say, ‘Oh look, you just did this. Why can't we do that?’”

It may be, Mueller said, that the only way to overcome the nationalistic issues of the Internet is to overcome the nationalistic issues of the world. “It's a big ask,” he added.

“I just don't think that's gonna happen.”