Data center buildings don’t get much love. They are often unnoticed and invisible. If people ever become aware of them and make any comment at all, it is most likely a sneer.

"Data centers are like uncanny offices," says Tom Ravenscroft.

That’s actually a compliment, because Ravenscroft is a rare example of a data center architecture fan. But what the editor of Dezeen, the largest architecture and design magazine, likes is their unsettling strangeness, their contradictions.

Uncanny offices

As an architecture student, Ravenscroft’s Master's project was an exploration of London's hidden data centers, sparked by seeing a building in Lewisham, South London.

The six-story block had windows and looked like some sort of uninspiring office block. But windows were blank, no staff came and went, and there were no cars in the car park.

He found out this was Citibank’s London data center, and he began to uncover data centers hidden all over London. The Wordpress blog documenting his travels is still available, and he has led walking tours of London’s data center sector.

"These buildings have reflective windows, they are dirty and they look neglected,” he said at a London exhibition about data center architecture. “And yet, they have high security."

Ravenscroft sees urban data centers as buildings trying so hard to be anonymous they are unmistakable.

Architecture winner

Others find things to like about data centers. DCD has issued a series of awards to Beautiful Data Centers, or those with particular architectural merit.

This year’s winner was Ashton Old Baths in Greater Manchester UK, a 19th-century municipal public swimming bath, originally designed by Paull and Robinson, which was closed and lay empty for 40 years, before Tameside Council converted it into a tech hub, with 10,000 sq ft of office and coworking space, and a 200kW data center.

The finished product looks special because of a factor that made the data center difficult to install. The building is Grade II* listed by Historic England for its architectural merit, putting it on a par with the iconic Battersea Power Station in London. That put a strict limit on what the data center builders could do.

“As engineers we tend to try and put holes everywhere for ducts and so forth,” says data center designer Zac Potts, at Sudlows, the firm that built the Ashton Old Baths data center.

“We had to meet the requirements of the engineering perspective, and restrictions imposed because of the building’s heritage,” he said. “We needed apertures and penetrations cut out of the building, but we had to work within the original windows and doors to route services out without damaging what is left of the building.”

There were restrictions on planning: “We couldn’t drop surprises with our ductworks. All the penetrations had to be planned out quite meticulously.

"We had to send information through to the heritage team, and there were lots of hoops to jump through. Every detail had to be approved.”

The Council’s heritage team were keen to prevent damage to the existing building, and make sure everything had to balance with the existing colors and styles.

To meet these demands, architects MCAU designed a freestanding wooden “ark” structure independent of the building shell to hold the new office space and the data center.

Sudlows and the engineers had to work closely with the architects to make it work.

Is old better?

Many of the data centers that feature on DCD’s award shortlists were installed in existing spaces, where they had to make the best of the limitations and opportunities.

In Stockholm, Bahnhof’s Pionen data center turned a former nuclear bunker into a glossy lair high-tech lair worthy of a James Bond villain.

The MareNostrum supercomputer nestles its server racks into the warm-hued stones of a 19th-century church, on the campus of the Polytechnic University of Catalonia in Barcelona.

Another church, the Salem Chapel in Leeds, became a data center where the servers are installed on the ground floor of the old worship space. The balcony was kept, and turned into a conference auditorium, looking down on the data center through a new glass ceiling.

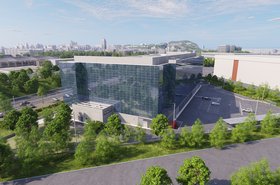

But retrofits are a tiny minority of data centers. Vastly more are in new buildings, which have to meet multiple demands.

They have to fit in with their surroundings, satisfy planning regulations, and also please any local residents - all alongside the need to satisfy the technical requirements of the data center. And underlying all that, they have to meet a budget.

Architects are a big part of that.

A new building type?

"Data centers power modern life and yet they’re rarely considered as pieces of architecture," said Clare Dowdy, curator of the recent London gallery exhibition of data center architecture, Power House.

"But as they mushroom across the globe, it’s time we thought of data centers as a peculiar, and peculiarly challenging, new building typology."

Potts, like most data center builders, has more modest aims: “Newly-built data centers, are usually pretty ‘nice’ buildings, but from an architectural point of view they are normally fairly understated.”

Young tech companies may want a state-of-the-art building, but they don’t want to show off their data center.

They want the building discreet, partly for security reasons, so it doesn’t attract attention from vandals, terrorists, or environmental activists. That’s the fundamental reason for the “uncanny office” effect noted by Ravenscroft.

A discrete look is also important for aesthetic reasons, particularly in urban areas where people will see the building. No operator wants to alienate its neighbors.

There’s a tension between the engineering demands and the need for a ‘plain’ look, says Potts: “How do we integrate things like diesel generators and chillers with a plain architectural look? We also have to provide airflow and acoustics.”

A good architect will be able to work closely with the engineers, and may surprise them: “From an engineering point of view we say what we need,” says Potts. “They can usually integrate that and make it into something special. They will work with colors, lines, and the edges, to produce something you wouldn’t have envisaged.”

He says: “We start with clean lines and symmetry. Architecture adds an extra layer on that.”

Architects who have done similar projects should be able to help with constraints like the thermal performance of the building, so it meets regulations and operates efficiently. They can also add fresh ideas.

“Working with a good architect really helps,” says Potts. “We focus on the data center aspect. An architect with some understanding of data centers can be involved at the very early stages and engage in those conversations.

A good architect might spot opportunities that could be missed otherwise - perhaps suggesting where a data center should go within a mixed-use building, or where to place it in a large development.

“There can be opportunities for heat reuse, or for mitigating where pipes and maintenance go,” says Potts. “Often data centers on a commercial estate can get tucked away into the most awkward position.”

Getting the architect in early can help make sure the project fits: “They will consider things other than the engineering,” he says. “Our aspiration is to improve the area, through its presence. Rather than detract from it.”

Budget can be an issue: “If you boil down to the absolute bare bones, you would end up with an ugly building with not much consideration for the area,” says Potts. By contrast, an attractive tech hub can encourage other buildings and businesses to work together.

“That’s why there’s a lot of focus from master planners and developers,” he says. “Just look at the margins, and you might bet a gray box, but that doesn’t improve the area so you need to look at doing something else.”

What that something is, is undefined. There’s been a trend for “exposed services” which leads to visible ducts and cables all over retail spaces. But data center operators don’t want that, except in the inside of the building where practicality is all that matters.

On the outside, there’s usually not much budget for extravagant decorations, but a strong desire to minimize the impact of the building and, usually, to obscure its technical nature: “Louvers and cladding can make sure the diesels and chillers are integrated in well.”

There is also likely to be some landscaping around the buildings, combining the ubiquitous security fencing with a screen of trees and some grassed banks.

“We focus on the engineering constraints, says Potts, “but it’s about achieving a balance and making sure the data center looks beyond the IT, to see the potential for creating improvement to the area, instead of just taking from it.”