You might think that the issue of air purity in data centers is done and dusted, so to speak. We all know how to handle electronics, and the dust and pollutants in air are well understood. However it turns out that air contamination is a live issue and attempts to clean up other parts of the data center environment could have unintended consequences on the atmosphere inside the data center.

Think of the whiskers

Firstly, regulations have removed lead from the solder that is used to attach components to printed circuit boards (PCBs). The European Union’s Restriction of Hazardous Substances (RoHS) Directive of 2006 banned lead in solder, in order to keep it out of electronic waste, and this effectively ruled lead out for the global electronics industry - though some people questioned the logic, as in fact very little lead escapes from waste into drinking water.

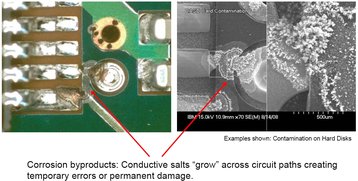

What’s that got to do with air purity though? Without lead, solder is less robust. It’s more susceptible to corrosion caused by pollution, and it also grows tin whiskers, which can break off become airborne and cause short circuits. Without lead, our electronics became more susceptible to air pollution - and started to produce their own.

At the same time, to make data centers use less energy and reduce their carbon footprint, designers started using outside air to cool the facility. It’s more efficient than cooling air down inside the building - but it adds to the risk of outside contaminants getting in.

“Contaminants can be introduced during infrastructure upgrades, or by simply opening doors while entering or exiting a white space,” say Paul Finch of Kao Data and Chris Muller of Purafil in a recent DCD article. “These contaminants affect electronic equipment, corroding components and reducing capabilities to failure point, which can result in costly data center outages.”

And finally, the location of data centers is changing. Edge computing means putting resources close to the end users and devices that need them - and that tends to mean digital infrastructure being placed in more urban areas, where there is a risk of particulates from diesel engines along with sulphates and other impurities.

Even some remote areas have special considerations: Iceland for example generally has some of the purest air around, but it has infrequent volcanic eruptions. In 2010, one of these produced enough particulates to ground flights across Europe (though ironically not flights from Keflavik International airport, or the main data centers locations which are 250km away and upwind of any volcanoes).

There are recommended procedures to deal with all these risks, like any other risks - and these boil down to understanding what is going on, planning, monitoring, and having a response ready.

The first thing is planning: outside air can be run through a heat exchanger for indirect cooling, and filters should be put where there is a risk of contamination.

Back in Iceland for instance, Verne Global’s campus has a wall of air filters that can take out volcanic ash particles within air. As rare as an eruption is, if the levels ever got too high, the filters can be shut, and the facility will run on recycled air. Urban data centers in places like London, New York and Paris have to make similar plans for constant road traffic pollution.

Monitoring is straightforward: sensors can measure contaminations, and these should be networked wirelessly, to give a real-time picture of air in the data center, as well as archived reports of the quality, to give advanced warning of any issues.

All data centers are designed for a level of reliability: keeping the air clean is just one part of that.

This opinion originally appeared on Verne Global’s data center industry blog