Solar power has been getting increasingly popular - but what happens when we get solar overkill? How worried should we be about solar flares? An article on the subject posted on DatacenterDynamics’ LinkedIn page prompted me to ask the question, and the answer is that solar flares are something you should at least be aware of.

Solar storms

A solar flare is when a burst of energy emerges from the Sun. You can think of it as a bubbling saucepan boiling over - though the physics is different because the sun is actually a “plasma” of ionized gas. It is a stew of magnetic fields that sometimes “reconnect” in a topology that suddenly accelerates particles, creating kinetic energy produces flares and “coronal mass ejection” where a bit of Sun is spat out.

Most solar flares are harmless, but coronal mass ejections travel outwards: what happens if one hits the Earth as it orbits the Sun? Well, it;s not the end of the world. The human race has already survived at least one such event.

The Carrington Event

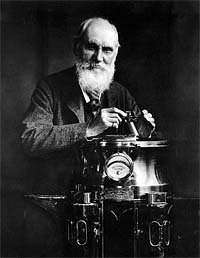

In September 1859, Richard Carrington, a British astronomer who studied solar activity, observed a solar flare. The next day, it hit the earth, creating the greatest geomagnetic storm ever recorded, now known as the Carrington Event.

The aurora borealis (or Northern Lights) appeared round the world and in the Northern US were bright enough to read a newspaper by. Telegraph systems were disrupted, with operators getting shocks and some sparks causing fires.

Magnetic fields induce electric currents in a conductor, so a big magnetic storm can generate spurious signals and currents. It’s safe to say that a Carrington event would take out large parts of the Internet (and possibly data centers), and it might take hours or days for some systems to be restored.

Fortunately, these storms are rare. Analysis of polar ice suggests they happen around once over 500 years. But that’s an average frequency, not a time table, so one could happen any given year. In 2012, a Carrington-level solar storm crossed the Earth’s orbit, missing the Earth by only nine days. Since 1859, flares big enough to disrupt radio systems have occurred in 1929, 1960 and 1989.

So, what should you do?

The article that prompted all this suggests you should include solar flares in your disaster strategy. This is true, since they are a real (but rare) danger.

However, though the damage could be large, the probability is low, the failure scenarios will be very complicated to list out, and expensive to counter. Proofing your facility against all the more extreme possible results of a solar flare is a lot like proofing it against the more extreme electomagnetic pulse that could be caused by a nuclear device.

So yes, be aware of it. But if you try and proof your data center completely against solar storms, you could bankrupt yourself preparing for something that doesn’t happen. And in any case, if it does happen, your customers may not even be able to use your data center until global networks are restored, so the expense would be wasted for another reason.

If you would like to learn more about solar power register now for our “Powering Big Data with Big Solar” webinar.