When Herb Zien, who used to run the largest operator of urban district heating and cooling systems in the US, saw for the first time how data center operators were cooling their facilities, he was shocked.

As a former thermal engineer Zien was surprised that cold air was being pushed onto the IT equipment from underneath, when cold air tends to fall down. But what surprised him most was that the cooling medium was air, which he had used as a temperature insulator, not as a conductor.

“Maybe there’s a better way to do this,” Zien thought. This was towards the end of the past decade. Zien and a partner had sold Thermal North America, which owned and operated steam, chilled water, hot water and electricity distribution systems in 11 US cities, to Veolia Energy.

It was clear to Zien that data centers would become the next major energy consumers. His interest was piqued by a company based in Rochester, Minnesota, that was demonstrating an ability to overclock CPUs on gaming computers by submerging them in dielectric fluid. He became an investor in the company, a board member, then CEO – a role he still holds.

The company, called LiquidCool, does more than cooling gaming PCs. With its 16 issued and 24 pending patents it licenses liquid cooling technology to electronics manufacturers, and the data center market is one of its primary targets.

So far, the company has licensed the IP to flight simulators for pilots. But there has been interest from one of the major IT hardware suppliers, as well as from a modular data center vendor. Zien says LiquidCool’s technology offers lower total cost of ownership (TCO) than other data center cooling systems, can accommodate more servers per rack and increase data center reliability.

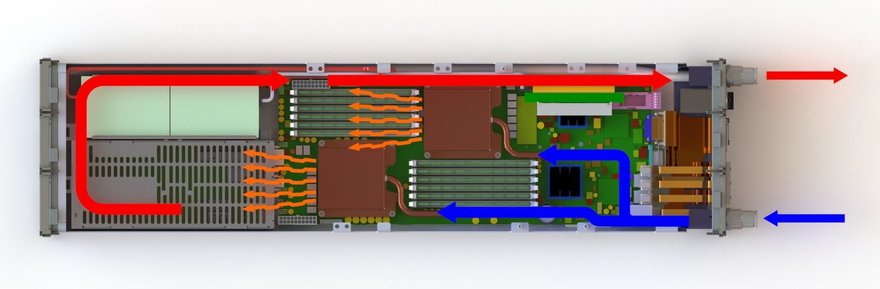

Rather than dipping servers in a tub-like rack filled with dielectric fluid, LiquidCool’s approach is to seal each server hermetically and fill it with the fluid. This way the system is compatible with standard IT racks.

The company’s cooling liquid is called Core Coolant. It is a non-hazardous, non-volatile, low-density dielectric liquid that can absorb 1,400 times more heat than air.

Inside each server, the coolant is pushed directly to the hottest components, while the other parts are cooled by the non-directed bulk of the liquid, before being pumped out of the box for heat extraction. Warm fluid up to 113°F is pulled into an evaporative fluid cooler before returning to the servers.

Liquid cooling tactics

In addition to lower TCO, the biggest benefits of LiquidCool’s approach are increased reliability and longer life of IT equipment. The temperature around solder joints does not fluctuate as much which helps reduce joint failures.

Corrosion of electrical contacts is also stopped because they are not being exposed to fluctuating air temperature oxidation. There are no fans, so there are no moving parts, which means less potential for failure, and no electrical contacts to deteriorate from constant vibration.

Finally, the electronics are not exposed to electrostatic discharge, ambient particulate and humidity.

Green Revolution Cooling, Asetek, Chilldyne, CoolIT Systems, Clustered Systems and IBM provide liquid cooling solutions that are different types of cold-plate technology. Instead of flooding electronics with cooling liquid, a cold plate is bolted onto the server CPU, and the cooling liquid is supplied to the cold plate.

According to LiquidCool, cold plates cool only the hottest components. The company’s logic is that while cold plates keep the CPUs cool, they save neither space nor energy. The servers still need fans and the room still needs to be air conditioned.

Other competitors offer ‘cold-wall’ solutions. Rittal provides a cold-wall system where a water-to-air heat exchanger is installed between IT racks and blows cold air sideways using fans. And vendor SprayCool has a system that sprays dielectric fluid on electronics.

As the fluid evaporates it gets colder and cools the components. The vapor condenses and moves to a heat exchanger.

The closest solution to LiquidCool’s is that provided by UK-based Iceotope. Like LiquidCool, Iceotope floods the motherboard, inside a sealed case with coolant but the case includes a piping circuit that carries water to cool the coolant.

This article first appeared in FOCUS issue 35. To read the full digital edition, click here. Or download a copy for the iPad from DCDFocus.