A £2.6 million ($3.3m) international project will investigate storing waste heat from an Edinburgh University supercomputer in old mine workings, before using it to heat local homes.

The University of Edinburgh’s Advanced Computing Facility (ACF) already has a supercomputer, and is scheduled to host the first exascale computer in the UK in 2025. The Edinburgh Geobattery feasibility study will examine the idea of storing hot water at 40oC in disused mines before using it for domestic heating in the city.

The University's announcement estimates that the heat from the ACF could warm at least 5,000 households if the feasibility test proves practical.

The ACF releases up to 70GWh of excess heat per year (which could equate to around 8MW of average heat power). This is due to increase to 272GWh (31MW) once the UK Government’s recently announced next-generation exascale supercomputer arrives.

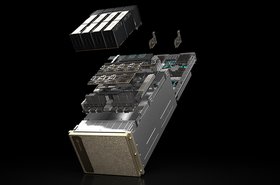

The government has not yet announced details of the new exascale system or who will be building it. But the system, due to be installed in a £31 million ($39.24m) purpose-built wing of the ACF, will certainly use liquid cooling like all modern high-performance computing (HPC) systems.

Using waste heat output is often proposed as a way to operate more efficient data centers, but transporting the heat to where it is needed is difficult. Some installations in Europe are being sited at existing district heat networks, to make use of the warm water they output, while other startups including the UK's Deep Green are producing smaller compute systems that can be placed at sites like swimming pools, with a constant need for heat.

In other places, such as West London, new district heat systems are being built.

Edinburgh has some district heating networks planned and in operation, but it is also near networks of abandoned coal, shale, and mineral mine tunnels, which are already flooded with water.

The project will look at transporting the supercomputer's waste heat to the mine workings "by natural ground water flow," and then using heat pumps to move that energy, so it can warm people’s homes.

The University says "a quarter of UK homes" are "sitting above former mines," which means potentially seven million households could get heat this way.

The Edinburgh Geobattery project is being led by Edinburgh-based geothermal company TownRock Energy and also includes industry and academic partners.

The lead research partner, the University of Edinburgh is putting in £500,000 ($633,000) of funding from its own net zero initiative funding, and Scottish Enterprise has awarded the Geobattery a £1 million ($1.27m) grant through its Joint Programming Platform Smart Energy Systems (JPP SES) and Geothermica, which will pay for researchers from University College Dublin.

The US Department of Energy is also putting in $1 million to fund researchers from the Idaho National Laboratory and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory. The University of Strathclyde is another partner.

“This project opens up the potential for extracting heat stored in mine water more broadly," said Professor Christopher McDermott, from the University of Edinburgh’s School of Geosciences, lead academic on the project. "Most disused coalmines are flooded with water, making them ideal heat sources for heat pumps. With more than 800,000 households in Scotland in fuel poverty, bringing energy costs down in a sustainable way is critical, and using waste heat could be a game-changer.”

David Townsend, founder of TownRock Energy, said: “Capturing, storing, and re-using waste heat is critically important to reaching net zero, and here we are learning and testing how best to do this in the ground, in legacy coal mine infrastructure."

Suzanne Sosna, director of energy transition at Scottish Enterprise, said: “I’ll watch with keen interest how gigabytes can turn into clean heat as the Edinburgh Geothermal project progresses. This initiative also highlights the energy transition market opportunities available for Scotland as we strive for net zero.”

DCD has contacted the University of Edinburgh for more details of the scope and timelines of the project.