There’s a simple cause and effect in data centers – they produce heat. Lots of it. And the more compute power, the more heat gets produced. With the advent of ever-increasing loads from new applications such as artificial intelligence, we’ll see more data centers producing more heat.

Older air-cooled solutions won’t do anymore, traditional liquid coolants are suffering from short supply (such as, most notably, water), and in the case of chemical-based alternatives, they can fall foul of environmental regulations.

There’s also another quandary. Why are we letting all this heat simply dissipate in the air, compounding the problems of global warming?

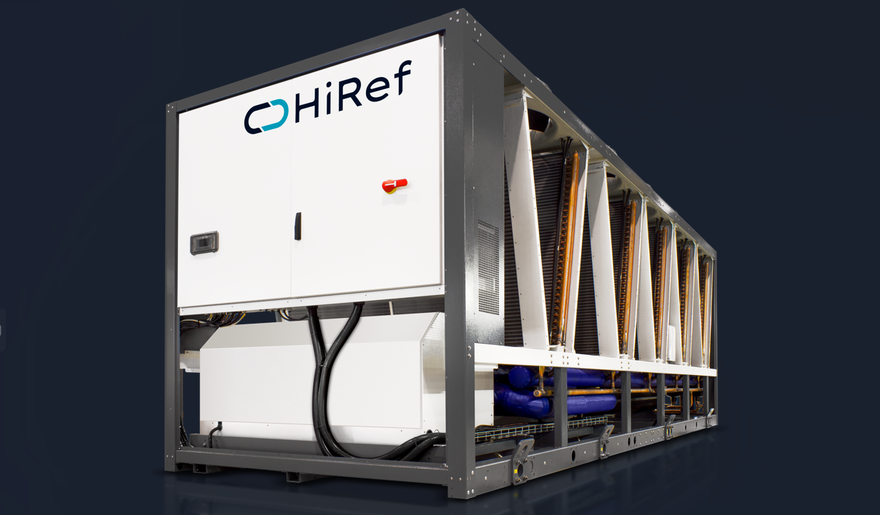

Fortunately, the moment has been prepared for. Since 2001, HiRef, an industrial cooling and air conditioning specialist, based in, Italy, has been at the forefront of innovation, whether it be new form factors of chillers, alternative coolants, and more recently, the advent of affordable heat energy reuse for domestic and commercial heating.

DCD spoke to Wolfgang Fels, HiRef’s commercial director, Annagiulia Debattisti, Chillers & Heat Pumps senior product manager, and Jaap-Jan Pethke, international key account manager about the latest innovations in environmentally sound coolants, and the challenges associated with turning waste heat into a useful asset.

2023 has seen record-breaking heatwaves, with devastating wildfires raging across parts of Europe. We start by asking if these temperatures, set to be the shape of things to come, have altered the roadmap of the business. Fels tells us:

“Recent years have seen a major focus on the reuse of waste heat from data centers in the sector, due to the increase in the global temperature. Therefore, the approach to the market for many has changed.

However, unlike our competitors, we had no major effect on our roadmap, purely because we have always put sustainability front and center of product development.”

As the world continues to heat up, water has become an increasingly scarce resource in parts of the world. However, with air cooling proving insufficient for so many hyperscale data centers, the need to find alternative liquid or gas coolants has been expedited. This isn’t a problem for HiRef, however, who has been actively developing alternative coolants, long before they became a requirement.

“We decided to explore alternatives with natural refrigerants as far back as 2006 before we even knew we would have to comply with the main requirements of the most recent F-Gas regulations (Fluorinated Greenhouse Gases Regulations 2015) which required a reduction in the use of traditional coolants to reduce greenhouse emissions.

"In general, on external units, or chiller or heat pumps, the use of new gas is important and we’ve had to find ways around problems related to flammability, which is a feature of many new refrigerants, making them wholly unsuitable. For internal units, it can be even more vital because these are such critical points of the data center hall. That has led to the development of CO2, which is an excellent refrigerant but which is not flammable.”

The advantages of alternatives, such as CO2 are plain to see, however, it is only recently that pricing has made them a viable financial choice for businesses as Fels explains:

“It comes back to the GWP – global warming potential, which is a measure of factors causing the greenhouse effect. That’s why it’s so important that we reduce the quantity of coolant and therefore stem the greenhouse effect, by using new refrigerants that reduce emissions from a ratio of GWP 500-600, right down to a GWP value of six, or in the case of CO2, for example, the GWP value is almost zero.

“Back in 2014, Annagiulia wrote her master's thesis on the use of CO2 as a refrigerant – so it's not that new as a concept, and even now, it still has its limitations, such as higher costs compared to synthetic refrigerants. However, the price differential has been on a downward trend since back when Annagiulia was writing her thesis which, in itself, represents a huge milestone for us. That’s when we saw a big future in CO2 as a way of reducing our products’ GWP and that has shaped our roadmap over the past five years.”

“When it comes to data center cooling, Turbocor and liquid cooling are two very interesting technologies. Turbocor (a type of centrifugal compressor) is typically a very effective solution for partial loads in data centers and those with lower ambient temperatures.

"Turbocor compressors are generally used more in co-locations in traditional data centers. Liquid cooling is a completely different approach providing very high efficiency, and the heat is a lot easier to dissipate and then harness the excess for reuse. Liquid cooling is generally used more for supercomputers and solutions where you need or require a tremendous amount of compute capacity.

"That said – traditionally, liquid cooling would have only been in the realm of possibility for hyperscalers and similar kinds of clients. These days, liquid has become more accessible and its use could also encompass universities and industries where they need to do many intense calculations, such as for 3D modeling."

Heat pumps in the data center

Today, the focus is increasingly on finding ways to harness the extraordinary amount of heat generated by server arrays. HiRef is developing technologies and optimizing these by adding heat pumps to the data center, the waste heat can then be taken from the source and redistributed to nearby premises, offering a cheap, green alternative to gas or electric heating. Debattisti tells us more:

“It seems a bit strange to think about heat pumps when we’re speaking about data centers or cooling processes in general, but in this case, we can think about the waste heat not only as a by-product from the source but as an opportunity. In this case, the pump is not the simple one, but a version specifically designed for harnessing heat recovery at medium-high temperatures, and to produce high-temperature water at a level suitable for industrial or civil heating – for example, district heating.”

But how does this happen, in practice?

“In particular, we speak about temperatures of the cold water down to 7°C which is the minimum, with contemporary production hot water of up to 90, or even 120 with cascade systems, which is the limit of current technology These heat pumps can be used either directly as a cooling machine for the data center and at the same time as heat pumps for heat production or they can be coupled to the dissipation sides of the main cooling generator while still providing heat for general use (i.e., civil heating) on the user side. Depending on the temperature level of the data center it’s possible to have a single-stage heat pump or a cascade system. In general, the trend of the temperature increase of data centers helps to increase their efficiency by reducing the gap between the source and the user side of the heat pump.”

Although it is only recently that we’ve heard so much about the idea of waste heat reuse, HiRef has been pioneering schemes that do just that, dating back to 2007, as Fels tells us:

“My previous background, before starting in IT cooling, was in the heating industry, so when I first became involved in data centers in the late ‘90s, I always wondered why the heat load from the room was just left to be distributed to the ambient. That's a big waste. Why lose all that energy? So I tried to understand it and realized there was no real reason and at that time no intention to combine both. I was a little bit disappointed by that, but it was always somewhere in the mindset of our company, right from when we were founded, to try and solve this disconnect. What should we do? How can we integrate it? What kind of opportunities are there?

“We didn’t push it to the extreme at that time, but we started talking with customers about where the opportunities lay in this field. Then in 2007, we started a project with a small data center to use their heat energy for some smaller heat pumps, and some nearby office blocks, but it proved a prolonged process to get both sides together – a client offering to distribute the waste heat and another who needs it. We’d keep finding roadblocks, like one side may not be happy that the other could be 100 percent secure of the availability, which stalled negotiations, so it took a long time to become a reality.”

So, we wonder, if the facility to reuse waste heat dates back nearly two decades, is it a lack of understanding by data center operators that has led to the slow uptake of such schemes? Is it a matter of education?

“I don't think it’s necessarily important to educate, I think the matter is widely known in the industry. I think what’s needed is more incentives at a local level to take part in such schemes. I understand that in Frankfurt, they are now trying to only permit projects that will demonstrate the end use of the waste heat, at least partially, and that’s the type of scheme that we need more of.”

One of the issues that could be off-putting to developers is the extra equipment required to harness waste heat, and not all data centers are suitable to simply plug and play into domestic heat sources. Debattisti tells us what’s involved from the data center side:

“It depends on the layout of the data center. Some older data centers work with quite low temperatures on the water side, sometimes as low as 12/7°C. In these cases, applying a heat pump to generate cooling capacity at this temperature and then raising it to 80-90-100 degrees for reuse can be very inefficient. In this case, the best solution could be to have cooling units that cool the data center directly while the heat pump recovers the heat from this cooling unit, generating high-temperature heat.

When it is possible to have dissipated heat on the water-side, it is quite simple to apply heat pumps, therefore the heat pump can also be added later, so it's not something directly impacting the data center layout but can be added later as a side unit.”

With a proven track record of innovation comes an expectation of being constantly ahead of the curve. As the urgency for solutions to climate change has increased through regulation, as well as public awareness, has there been any pressure on HiRef to keep coming up with the ‘next big thing’? What are the main stumbling blocks for innovation? Pethke tells us:

“There is a lot of discussion about refrigerants and Annagiulia already talked about the F-Gas regulations. There is a lack of clarity in these regulations, and we see the speed of change in refrigerants moving at a very fast pace.

"Every time a new synthetic refrigerant is introduced, a couple of years later, something ‘wrong’ with that refrigerant is detected, so we are going more and more in the direction of natural refrigerants. We see the market suffering from this lack of clarity and this makes our industry focused on a lot of different directions, implementing a lot of different solutions for the various refrigerants. That means there is no clear roadmap for our industry's future. That makes it a little bit more difficult.”

When the concept is more advanced than the technology

The innovation is hard to ignore. Are there any projects you’re particularly proud of?

“We get a lot of questions coming from the market, and recently we had the fortunate opportunity to work with a client involved in Formula One, and introduced the first free-cooling CO2 chillers for data centers in that market. As far as we know, we're probably one of the first to provide this sort of technology.”

One of the problems with innovation is that sometimes you can find yourself with ideas that the market simply isn’t ready to turn into reality, as summarized by Fels:

“The pace of requests from the data center market is coming much faster than in the past, which means the challenges for us to react are coming faster too, no question. Since we are used to applying the newest technologies in terms of energy, refrigerants, or whatever was requested, we saw a future trend in the market. Remember, we introduced our first chiller with ammonia in 2006 when nobody was talking about natural refrigerants. The only thing was that the market was not prepared to pay the difference in terms of pricing, but it showed that we were always ahead of the competition, and the trend of the market.

“Now the pace for development is much faster, but the requirements and regulations from governments are also being introduced much faster which creates difficulties for us as a manufacturer because if you have a new refrigerant coming onto the market, then you need to have new compressors, new refrigerant components, and so on – but component companies need time for the development of their products. So we are limited, not from our side, but we are limited by the availability of updated components from our suppliers.”

Regulation frustration

That suggests to us that your attitude to regulation is often one of frustration.

“I believe the regulations that we have, at least from the EU, can be more confusing than helpful to the industry. With the instructions we have, you need to reduce as the number one priority, but nobody takes into consideration that there are certain time limits, which we'll need to take in, and which need to be respected.

"The same is true with discussions on PFAs (Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances). We have to interpret EU regulations that simply say, ‘Well, you need to do this’. They don't think about the consequences or difficulties and how much impact it has on the industry. So in my opinion, institutions should seek input from experts who know the industry and are kept up to date with the decisions of the EU.”

The obvious stumbling block here is the supply chain, which was severely affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. However, in reality, the barriers to realizing innovation are more fundamental:

“It is not just related to the supply chain, there was a difficulty on top of what was coming from the pandemic. Big companies have a certain quality standard, so they are forced into following certain quality guidelines. That means testing a variety of compressors to find the right solution, which all takes time. It all comes down to time. For this reason, we can provide solutions for a certain kind of product part, not the entire range, for example, to whatever kind of component is required. And so this is slowing down our process, rather than the expected pace.”

So, we ponder, what would it take to mitigate these roadblocks?

“It's beyond our capability to influence, but of course, the industry needs to develop much faster. I don't know how realistic it is to think about it. If you develop a product, it takes one to three years – we have to make sure it is tested and tested through the quality process. So there’s a natural limitation of the time to market. If we were able to reduce the time to market with the manufacturers, that would help very much – but that’s simply not realistic any time soon.”

The wisdom of youth

In previous conversations with HiRef, we’ve learned that one of their ‘secret weapons’ in staying ahead of the competition comes from an extensive partnership with local educational institutions which brings a constantly evolving workforce of fresh minds, and new perspectives. Does HiRef see that as a major factor in its continued track record of predicting industry trends? Pethke talks about this aspect that has proven so successful for HiRef:

“Young students come to our company, without antiquated mindsets, thanks to the school and teaching practices they have experienced, there’s already a different mindset in terms of sensibility process and sustainability. It doesn't change the direction of the company. We were always geared up for the newest technologies because of the close collaboration we have with universities. It gave us an insight into what will happen and “what is what”, where the demand is coming from, and what kinds of trends and technologies are popping up in the future because normally these are the first people to get involved in these kinds of discussions.

“That’s why we appreciate students who come to us so much – they are completely clean in terms of business approach and business mentality. At a certain age, you become somehow business-driven, with a business mindset, unlike a student who is coming to you, fresh from university. They’re more likely to say ‘I see what you're doing. Why don't you do it like this?’ and sometimes you think ‘Wow! Because we've always done it like this, and it's not the right answer’. That makes us think, and we appreciate this type of input.”

Pethke adds, “What we can do as a company is create an atmosphere for young people to think and act this way which will allow them to share their thoughts, and so we give them space, because of our awareness of what they can bring to the table.”

Of course, it’s one thing to innovate, but companies at the cutting edge, like HiRef, also have to ensure that their innovations are also the most efficient they can be, as explained by Debattisti:

“We are constantly working to find new and more efficient technologies, in particular, collaborating with our providers of components. We want to be not only a provider of end-products, but in general, we like to be a partner with our customers to design innovative solutions, so it is really important to find as many ways as possible to integrate the flows, heating, and cooling.

“The other is focusing on a wider environment, and the concept of smart cities where the important thing is to convince and then work with the local institutions to think and develop solutions, then to create them as easily and quickly as possible – integrating not only the flows of a single building in a single industry but of a city, as much as possible.”

Come together

During our talk, a theme that comes up repeatedly is that of collaboration. Does HiRef share the view that collaborative efforts within our industry have become more important than ever? The short answer is that it takes two to tango and as Pethke tells us, without a conscious effort from both city planners and data center operators, waste heat reuse is nigh on impossible:

“If you want to reuse the heat from a data center, you will need to bring the data center closer to the people, to be able to reuse the heat, at least if you plan to use it for domestic stuff. The difficulty with this is that towns are designed and built and houses are built for approximately 100 years, whereas a data center is built for approximately 20 to 30 years. Even the oldest data centers are approximately 30-40 years old. If you want to reuse that heat, you need to integrate it into an infrastructure. Therefore, it's really important to bring those two together.”

More information is available at https://hiref.com/.