In 1988, while working for the steel and mining company Hoesch, Dr Karl-Ulrich Köhler visited a mine in Norway to discuss olivine, also known as the gemstone peridot. There he met works director Steinar Kvalheim and watched as hundreds of thousands of tons of the green mineral, used to tap blast furnaces in the steel industry, was excavated from the inside of a mountain.

Little did he know that twenty nine years later he would once again stand in that mine, this time with Kvalheim’s son, Sindre, and announce that Lefdal has a new use - as a data center.

Now CEO of German IT manufacturing giant Rittal, Köhler has big hopes for Lefdal, telling an assembled crowd at the facility’s launch: “We will be by far the largest data center in Europe once fully utilized.”

With Lefdal Mine Datacenter now open, the difficult, perhaps impossible, journey to full utilization of some 120,000 square meters (1,291,669 sq ft) of white space has begun.

But the desire to transform the mountain into a data center predates Köhler, whose company is the largest single shareholder in the project.

Caves of steel

Nine years ago, after the mine was abandoned when surface-level olivine was discovered just 10km away, regional hosting company LocalHost realized there could be another use for the empty mountain.

Heidi Grande Røys was Minister of Government Administration and Reform at the time, campaigning in the final months of her term. When in Måløy, she met LocalHost CEO Sindre Kvalheim and investors Gunnar Carlson and Egil Skibenes, who told her about their fledgling plan for Lefdal.

“They needed some money, but most of all they needed a government official to sign on and say that this is okay,” Røys told DCD.

Røys said she struggled with departmental red tape, but eventually was able to give the new venture half a million kroner ($75,000). “Then IBM said ‘okay the government is behind this.’”

“We worked with them on the project itself, on the business plan and design,” Laurence Guihard-Joly, GM of IBM’s resiliency services division, said.

The data center progressed slowly, with a delay when the company became “entangled with a large data center project outside of Oslo for two years, which was sold to DigiPlex,” Lefdal Mine Datacenter CMO Mats Andersson explained.

“Then we came back to Lefdal two and a half years ago and said ‘now we’re doing it.’ We raised the equity, we got the banks on board, and then we announced in August 2015 that we’re starting the build out.”

For the phase one opening, tenants have access to Level 3 of the mine “which will start to gradually fill up. When that gets to a certain limit, we will start on Level 4 and then Level 2,” Andersson said.

The mine goes deeper, but CTO Vidar Saltkjel said that the plan is to use just those three levels: “Below it, space is limited and there are even pressure challenges when you put something 120m down.”

Level 6 is occupied by pumping stations that remove the groundwater that seeps into the mine. “We’re trying to do it as effectively as possible with the right set of pumps, but it’s a facility issue and is part of the PUE,” Saltkjel said.

PUE (power usage effectiveness) is the leading measure of data center efficiency, and Andersson told DCD: “The PUE will never be more than 1.15, guaranteed.”

One of the reasons for that low PUE is an adjacent fjord, which provides a constant supply of cold water: the facility takes seawater from as deep as 80m down and pumps it out at sea level. On Level 3, the fjord gives the facility a cooling capacity of two times 45MW, “meaning a Tier III 45MW data center, or a 90MW Tier 0,” Andersson said.

He was unsure when the other levels will be needed, but said they can be “built out rather quick when we decide it’s the right moment, hopefully in a couple of years.”

A mountain ready to go

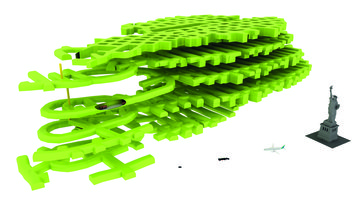

Any data center developer can buy space in Lefdal, but Rittal’s container-based solutions were most visible at the launch. The tunnels, which some in the company describe as “streets,” are wide enough to accommodate data halls built inside the mine, or else shipping containers stacked up to three high along each side of the tunnel.

“Data halls are regular white space, delivered by Rittal and built in weeks,” Andersson said. “Always 4m high rooms, 12m wide and varying in length, built in two stories.”

With Rittal’s large equity stake and close involvement, it is perhaps not surprising that one of the first customers of Lefdal is another business with close ties to the company - German-based Innovo Cloud, part-owned by Rittal.

Innovo operates in two standard colocation data centers in Frankfurt, as well as in an edge data center facility. “Rittal asked us to see if we could leverage Lefdal, and the answer for us was immediately yes because we want an ecosystem of data centers that are a bit different,” Innovo CEO Dr Sebastian Ritz said. “At first we were very skeptical about the network connectivity, but it turned out not to be an issue.”

Lefdal claims round trip time to London of about 17 milliseconds, 20ms to Frankfurt and 22ms to Amsterdam.

That said, Innovo appeared to be conscious of latency, initially targeting high performance computing “because HPC customers are not worried about latency.” It will also use its single starting container as a disaster recovery site for its cloud service.

Ritz said: “My hope is that we don’t have to sell Lefdal as a disaster recovery [site], because I feel you don’t serve them best as ‘oh it’s just a backup data center.’ We can use it as a full, active data center.”

IBM is also treating Lefdal as a backup facility at first: “We will start with backup and disaster recovery. We will not start with a container fully utilized from day one, but we can grow inside the [single] container,” Sebastian Epple, director of resiliency services in Europe at IBM, said.

Epple, like those at Innovo, believes that Lefdal works both for backup and for HPC customers, with flexibility making the site particularly attractive for the latter.

“There’s no need to rent a full hall like in an old traditional data center. You can grow as you need it. The density in those containers is quite high - you can have 30-50kW per rack, so you don’t need as many containers and racks as you might in a traditional data center.”

A new client

It was this flexibility that helped attract Lefdal’s latest customer, Fortuitus AG, which describes itself as “a Swiss technical infrastructure projects-financing consultancy, currently engaged in over a billion euro’s worth of projects stretching from Scandinavia to South Africa.”

“We have a very, very small footprint,” CFO Neil Collins told DCD. “Most operators said that ‘if you want 10MW, you’re going to have to rent 120,000 sq m.’

“Why? We only need 200 sq m, and forget all of your fancy services, we don’t want any of it. We just want a locked room where people leave our stuff alone.”

Fortuitus was at Lefdal’s launch to announce a 4MW HPC installation arriving this year, followed by another 4MW next year, and potentially 2MW more after that. It would not reveal the backers of the project, other than to describe the group as “financial.” A source who requested anonymity told DCD the company would be mining cryptocurrencies.

Whatever the system will be working on, Fortuitus’ first IT hardware iteration would not have been suitable for Lefdal due to the intense air cooling requirements.

“Genuinely you wouldn’t have been able to stand in here, it would have been a wind tunnel,” CEO Mark Collins told DCD, staring at the ‘street’ his HPC rig would soon be installed in, dubbed ‘Penny Lane.’

Lefdal looked at putting the air cooling infrastructure outside of the mine - “and then we told them how much noise it would cause. They had a sound engineer saying ‘no,’ this would have been heard all over, and this beautiful Norwegian landscape would have been ruined,” Neil Collins said.

Fortuitus settled on liquid immersion cooling using 3M Novec solution instead, cooled by cold water in Lefdal, which is in turn cooled by the fjord’s salt water:

“So we have three separate circuits. Our IT guys said that this is fantastic because we didn’t need all this extra stuff. It enabled us to save money and buy a lot more computing power.”

Lefdal edged out Iceland for Fortuitus, which wanted to use 100 percent renewable energy. “As for the US,” Mark Collins added, “we were less trusting of the regulatory environment. And with the [Trump] administration, it’s unpredictable and you’ve got to minimize risks.”

A safe bet in Norway

Norway’s Minister of Petroleum and Energy Terje Søviknes told DCD that he “hopes data centers will represent a new green industry for Norway. The most important thing is that we have a surplus of renewable energy. We have green energy, we have enough energy, and we have affordable energy.”

Egil Skibenes, chairman of the board at Lefdal Mine Datacenter, agreed: “Developing Norway as a data center country is at the core of the government’s new strategy,” he said.

But before Norway as a whole can even begin to pitch itself to the world as a data center hub, Lefdal itself has much to prove. If you need to visit your data center space regularly, this reporter - who took two planes, a ferry and a coach to get there - can attest that this facility is not for you. Nor is it for those requiring the lowest of latencies.

Perhaps it may not achieve its aim of becoming Europe’s largest facility, but it has certainly carved out a niche that could grow.

And, no matter what the mountain’s eventual fate, there may be a poetic quality to its rebirth. Rittal’s Dr Köhler said: “A loop has closed between this green mineral, olivine, which we were digging out of this ground for industrial purposes to make steel, and this green mine. All of a sudden that steel - as racks, containers, cooling units, hardware and so forth - is coming back.”

A version of this article appeared in the June/July 2017 issue of DCD magazine