The relationship between art, technology, and artificial intelligence (AI) has long been contentious.

With AI - and particularly generative AI systems - becoming increasingly prevalent, it is perhaps the creative industries that are most concerned about the impact it will have on their work, and whether it could potentially devalue and disrespect that which they have dedicated their lives to.

In April 2023, the Harvard Business Review published a report titled “Generative AI has an intellectual property problem.”

The article explained how generative AI platforms are trained on data lakes and question snippets including “billions of parameters that are constructed by software processing huge archives of images and text.” The AI then establishes patterns and relationships and uses this to make predictions or create new content.

Many argue that this generation of content is a form of plagiarism, but there are challenges related to taking such a claim to court. If a piece of art was created with AI by compiling several different artists' work, who owns it - the AI? Or the artists?

Near the meat packing district of New York City, an art gallery is embracing the relationship between art and technology and even describes AI as a collaborator.

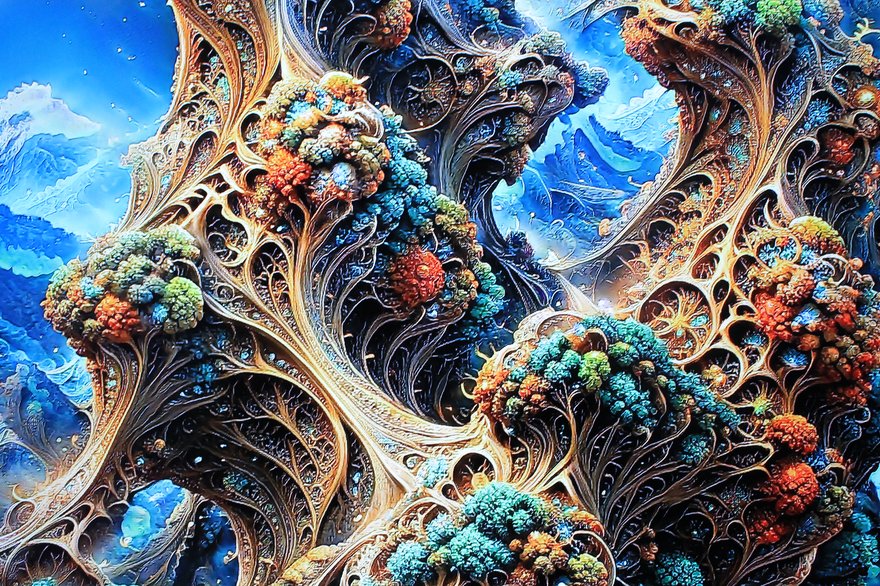

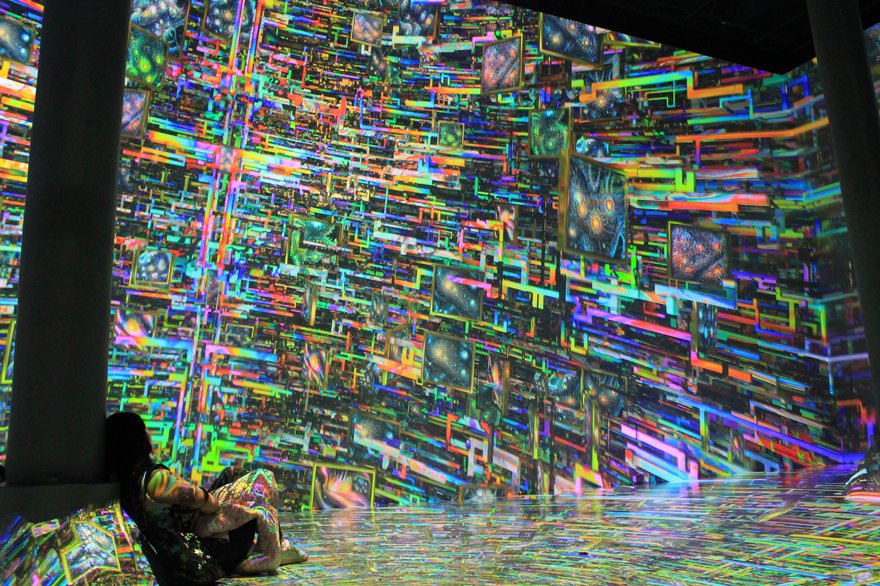

During DCD’s recent New York Connect event, we visited the Artechouse gallery for its “World of AI-Magination” exhibition and entered into a technicolor alternate reality.

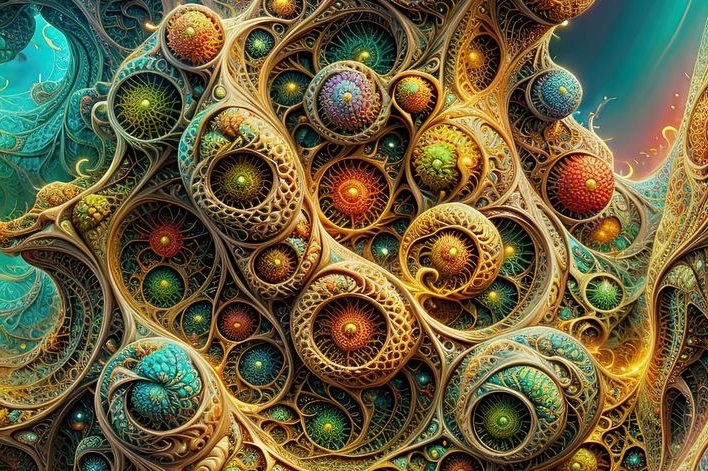

The art was created by Artechouse Studio - who developed all original visual materials for the installation using existing and custom generative AI systems, including Stable Diffusion and generative adversarial networks, with help from Nvidia’s research team -and is then displayed at the site via a mixture of interactive and non-interactive forms. With technology being such a key a part of Artechouse’s “secret sauce,” the gallery is unwilling to share intimate details about its setup.

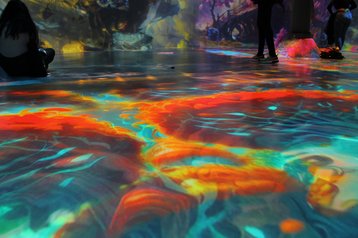

Artechouse’s New York venue consists of a large ‘immersive gallery’ that displays the art on the walls and floor of the room at a resolution of 118K, encasing you in the imagery.

“The centerpiece of the exhibition is the immersive gallery. That is rendered at such a high resolution that it can’t be interactive,” explains Rio Vander Stahl, digital director of Artechouse. “As I’m sure you can imagine, the amount of processing power that is required to render that is massive.”

To handle the rendering of what was a twenty-minute reel of artwork, Artechouse turns to its data center. Limited information was provided about the data center, but Vander Stahl confirmed that the team used servers equipped with Nvidia hardware to generate and process the content.

Part of Artechouse’s origin story comes from the company’s realization that there wasn't really a home for digital artists in a way that made the artwork an experience, rather than just an intangible piece viewed through a device screen.

“Artechouse fulfilled the need for that space, and we began working with artists. It quickly became clear that digital artists largely don’t have the studios or the digital infrastructure needed to do this at a large scale,” says Vander Stahl.

“A lot of the most creative and incredible visionary artists are working at incredibly small scales because that is what they have access to. So we began developing our studio to help artists produce their work.”

While the immersive gallery is pre-rendered and processed in an off-premise data center, some of the artwork is interactive, and that requires on-site processing.

“The majority of our side galleries are responsive, and depending on what that interaction is, there is a different amount of processing required,” explains Vander Stahl.

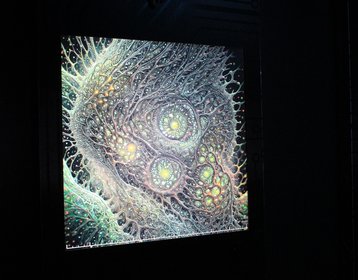

One of the pieces called Infinite Looking Glass is described as a “perpetually zooming digital tableau made possible through advanced AI algorithms.” This piece only commences when a sensor above it recognizes that a viewer is present. While interactive, this is probably more of an example of what Vander Stahl describes as “predetermined, point A to point B in terms of interaction.”

Some of the artwork is much more instantaneously generative. For example, several of the pieces of artwork that again use sensors can be manipulated by the viewer's movements, changing the fundamental composition of the piece in real-time.

In these pieces, which were housed in what was called the GAN Gallery (generative adversarial network gallery), the viewer gets a chance to play artist with the tools already deployed by the human and AI that created the basis for the piece. According to Artechouse: “Each piece of artwork in this gallery was retained on an average of 5,000 bespoke images, some even integrating up to 15,000 mixtures of original images.”

The end result means that each ‘visual experimentation’ is different, and no two viewers see the same piece.

In addition, there is a bar on the first floor of the gallery, behind which are screens displaying truly instantaneous artwork that is unable to be preprocessed.

The bar takes a snapshot of those sitting and enjoying a cocktail in real time and then generates a piece of work based on the image, which is then displayed in an almost virtual reality mirror effect.

“For the bar space, we trained maybe 50 or so different diffusion models on different artists' styles. The image is then processed in real-time onto one of those randomly selected models.”

As for the question of intellectual property, the artwork sourced is always from the public domain and is covered by fair use copyright and commercial laws. “We have selected artists whose work is in the public domain, but artists were curated based on historic or stylist choices, not necessarily to get a likeness of an artist's style,” Artechouse told DCD via email.

The exact details of Artechouse’s compute is sadly, a secret. Vander Stahl told DCD that it was a combination of both on-premise and off-site computing, but noted that “because of how our systems work, and because everything we do is proprietary that we have carefully crafted and cobbled together, there is definitely a lot of secrecy and protection.”

One thing Artechouse was able to confirm, however, was that processing is not done in the cloud.

In a follow-up email to DCD, the gallery said: “Each installation is unique, but broadly speaking, there is no graphics processing known at the scale or quality we present that can be transmitted via fiber or processed in real-time. Most of the work we do is visual, and visual processing is just way too heavy to do on the current cloud processing in real-time. Artechouse Studio has and maintains a render farm at a data center where a majority of this work is done.”

Presumably, that is then physically transported to New York City’s meatpacking district, for the general public to visit.