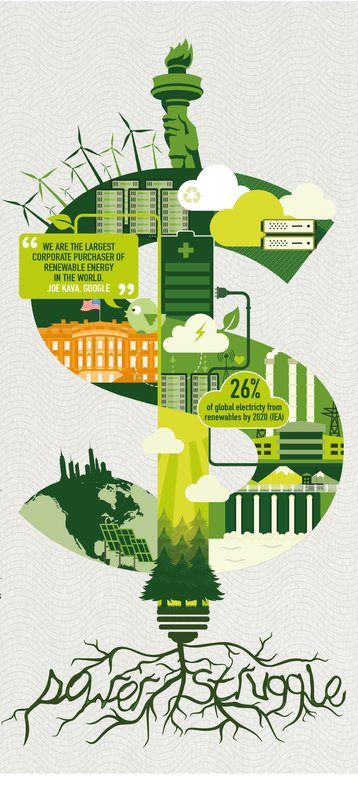

Whatever Donald Trump says about it, renewable energy is the future. Fossil fuels will eventually go away - and data centers are playing their part in the move to more rational power technologies.

Within hours of his arrival at the White House, US President Donald Trump’s administration posted an energy policy which said Trump is “committed to eliminating harmful and unnecessary policies such as the Climate Action Plan,” under which the Obama administration had promised to encourage alternative energy sources as a means to reduce man-made global warming.

Fossil policies

In its place, the Trump administration promises to support shale oil and gas, and to “revive America’s coal industry, which has been hurting for too long,” in a statement which makes no mention of climate change.

Soon after this, Republicans in Wyoming proposed a bill which would support the coal industry in that state - by making large wind and solar installations practically illegal.

These moves may fly in the face of established climate science, but they aren’t a surprise. Trump appears to be a climate change denier and spoke in favor of burning coal during his campaign.

But moving away from renewables is actually out of line with the direction of world power generation (see box). Although the majority of the world’s electricity is still generated from coal, oil and gas, renewable sources are rapidly moving to price-parity with fossils, and many countries report an increasing proportion of their power comes from renewable sources.

One thing that’s undeniable is that fossil fuels are finite, while renewable resources are effectively everlasting. Fossil fuels cause climate change, so we should wean ourselves off them, and leave them in the ground. But even if we don’t, they will eventually run out, and (fracking aside) will become more expensive to extract as we approach that point.

So data center operators have been making a shift towards renewable electricity and, at the time of writing, that position has not changed in response to the arrival of President Trump.

“We are the largest corporate purchaser of renewable energy in the world,” Joe Kava, Google’s senior vice president of technical infrastructure, told The New York Times in 2016. “It’s good for the economy, good for business and good for our shareholders.” Google bought 5.7TWh of power in one year (2015), about as much energy as consumed by the city of San Francisco.

Cloud leads the way

Speaking at the DCD>Enterprise show in New York in March Kava went further, explaining how energy purchasing deals cut by the big webscale service providers have actually enabled consumers to get renewable energy tariffs. Kava cited Taiwan as an example.

”It wasn’t possible to buy renewable power in Taiwan, but thanks to our policy team and the local government, new energy regulation was passed to allow consumers to buy renewable energy,” he told the conference. . This doesn’t only help Google, it helps everyone.”

In a similar move, Switch sued the utility NV Energy and the Public Utilities Commission in Nevada for the right to change provider and pay a competitive rate for renewable power. When Switch won its case, that right extended to other consumers in the state.

Good carbon accounting

Microsoft is on the same page. The company’s head of data center services, Christian Belady pointed out the necessity of good carbon accounting, which carbon credits are retired when they have been sold, so they are only counted once. ”Most companies don’t retire the renewable energy credits, ” he said. ”We as industry leaders should abide by this. That’s a key point.”

Most companies don’t retire the renewable energy credits.We as industry leaders should abide by this. That’s a key point.

Christian Belady

Microsoft Azure has also led towards more efficient power, Belady explained. Thanks to a deal with the local utility, Microsoft’s Cheyenne data center is sharing generators with the grid. This is more than just demand reduction: “The generator is the utility’s asset, but located on our site. It makes the grid more stable for everyone.” The project uses a gas-powered generator, and it provides energy for local homes and businesses as well as Microsoft’s facility.

As well as Google, Microsoft and Amazon, others have made similar promises, and other cloud providers including Equinix and Digital Realty are moving to renewables.

Fluctuating sources

On the face of it, however, renewables aren’t a great fit for data centers, or for much of the modern world’s power needs. Power grids need to have steady baseline power, and other sources which are able to ramp up and down quickly when demand fluctuates. That’s why the world has so many fossil fuel power plants.

They work for baseline generation, and it’s also easy to burn more coal or gas when more power is needed.

Hydroelectric power is steady and stable, so good for baseline power. Leaving aside nuclear, the other leading low carbon energy sources are solar farms and wind turbines, both of which are intermittent, fluctuating as daylight and wind come and go.

That’s why data centers rarely power themselves directly with renewable plants. They buy up the renewable power that is in the mix of the grid, offsetting the fossil u upower actually used in their facility. Even when data centers do have a solar farms or wind turbines on site, it feeds its intermittent energy into the grid while the grid feeds the actual facility.

When a data center pays for a “green” Watt, some say this only displaces the “brown Watts” to other users. But Kava and his colleagues say this stimulates the production of more renewable electricity, through the process of supply and demand.

Campaign group

There’s a group with the explicit aim of ensuring that more renewable energy is fed into the grid and consumed instead of fossil power: the Renewable Energy Buyers Alliance (REBA) wants to add 60GW of renewable power capacity to the US grid by 2025, and its backers include all the cloud giants: Microsoft, Facebook, Google/Alphabet and Amazon, as well as some 60 other companies.

Data centers are a small proportion of electricity use (around two percent by most estimates) and obviously an even smaller proportion of total energy use, which includes non-electric energy, such as fossil fuels burnt for heat and transportation.

Data centers can afford to take a moderate hit on power and lead the way to the new economy

But moving data centers to renewable power has become a campaigning issue for those inside the industry (such as REBA), as well as for groups campaigning from the outside, such as Greenpeace, which castigates the cloud industry for using fossil fuel in its annual Clicking Green report.

The reason for this focus is that data centers are modern and forward looking, and they have a reasonably high profit margin so they can afford to take a moderate hit on power and lead the way to the new economy.

Data centers are also at the heart of moves to fix the problems with renewables, making the generation match the demand of the grid better through demand management and other techniques.

Some of this will happen through energy storage. If data centers had battery storage, then energy from their local wind farm could be stored and used when required. The problem is that huge battery storage would be required, and batteries are still expensive (See Power Supplement).

Battery prices may be due to come down thanks to the electric car market, which could become a source of second-hand batteries. Once the performance of the battery falls below that required for a car, it still has enough capacity to store power on a duty cycle appropriate for providing backup in a data center. An Eaton product combines second-life Nissan batteries into modules which can power edge data centers.

Baseline load

This is a microcosm of what has to happen on a bigger scale, if power grids are to move to renewable sources. Hydroelectric power is a big win, as it can effectively be used for storage (close the sluices or even pump water back up to the reservoir).

But to make full use of intermittent sources like wind and solar, national grids need storage, to convert renewable power into dispatchable power. Most grids only have a small amount of storage now, which is nowhere near the TeraWatt hours (Twh) that would be required to turn enough renewable power into dispatchable power to support a whole power grid.

All this ignores the world’s continued dependence on fossil fuels, particularly for primary energy. As developing nations industrialize, they are still increasing fossil fuel use, leading to an increase in demand.

It’s been estimated by energy company BP that we may still be 20 years from the moment of peak oil demand, after which fossil fuel use finally starts to decline.

By that point, the world must be able to use renewable energy effectively.

In many ways data centers are acting as a laboratory for the kind of technology which will be needed by the rest of society terrifyingly soon.

A version of this article appeared in the February/March issue of DCD Magazine