A digital twin is a virtual copy of a building such as a data center - whether planned or already built - that will provide detailed simulations of how that building will perform and operate during its lifetime.

Though still a maturing space, digital twins offer a way for organizations to build data centers more efficiently and sustainably from the outset.

Through these complete digital doppelgängers, firms can optimize how their facility is designed, understand how it will operate, and spot potential issues before a single server is installed.

This feature appeared in the 2021 Building at Scale Supplement. Read for free today.

Data centers get their own digital twins

Subhankar Pal, AVP of technology and innovation at Capgemini Engineering, explains that a digital twin is a 3D virtual replica of your data center that can simulate its behavior under any operating scenario.

“A physics-based digital twin consists of a full 3D representation of the data center space, architecture, mechanical and engineering systems, cooling, power connectivity, and the weight-bearing capability of the raised floor. It encompasses the entire data center ecosystem, including virtual representations of the building blocks of your data center - the power, cooling, and IT systems components from all major OEMs.”

Such simulation software allows companies to predict, visualize and quantify the impact of any change in their data center prior to implementation.

“The digital twin brings all stakeholders together to foresee and take control of the performance and business impact of operations on your data center. The digital twin provides empowering visibility— reduce operational risk, remove process bottlenecks and analyzes ‘what-if’ scenarios all in one system,” says Pal.

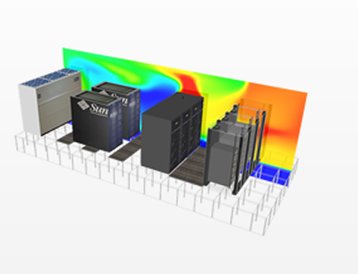

Malcolm Howe, critical systems partner at Cundall, highlights how the CFD models can optimize layouts before they materialize within the data halls. A digital twin can help remove some of the guesswork about deployment and distribution of IT load and capacity planning.

“Even small changes to the deployment can have a significant benefit in mitigating ‘hot spots’ and hence deliver better utilization for the owner/operator,” he says.

While it has potential benefits for ongoing operations of existing data centers, such simulation software allows companies to understand how their facilities will function in the real world. Companies can optimize data center designs with regards to hardware layout, power & cooling, and airflow. It is even possible to optimize building orientation for solar panels.

Firms can identify potential issues such as hotspots or fire hazards before the foundations of a facility are laid.

A key benefit of a digital twin is that it brings physics such as computational fluid dynamics (CFD) into view; liquids, gasses, and temperatures in 3D spaces are introduced into the picture, giving companies a much more granular view of how a data center will behave.

“Rather than using an exclusively data-driven model, data center digital twins are also physics-based, with the ability to simulate the performance of a new configuration,” adds Pal. “[It] empowers you to make decisions with confidence.”

When combined with technologies such as virtual or augmented reality, a digital twin can show facilities in full glory prior to construction and aid the building process.

Earlier this year PM Group announced it was deploying XYZ Reality's AR product Holosite during the design and construction of one of Europe’s largest hyperscale data centers in Denmark, to achieve “significant time and labor savings.”

As well as ensuring efficiency, simulation software can be used to create more sustainable design within the data center industry, says Joe Connolly, head of the Phoenix, Arizona, office and data center lead in the USA for Turner & Townsend.

“Selecting a building orientation can reduce energy requirements through things like maximizing daylighting. Building envelopes can also be optimized and can be designed with sustainable elements like water harvesting features,” he says.

“Energy modeling with a building performance simulation (BPS), run in tandem with a BIM model, could project energy consumption and look at the effects of including renewable energy options, like solar panels, and selection of sustainable materials.”

Benefits of digital twins after construction

When combined with DCIM (data center infrastructure management), digital twins offer a way for companies to understand and optimize the effect of hardware changes on the profile of a data center, and the same data can be used to help predict and automate operations.

“Most of the modern data centers built today incorporate some kind of engineering models at the design stage and extended the use of the model into the construction - and some even into the operation stage,” says Callum Faulds, director at Linesight UK.

“The digital twin, integrated with management tools such as DCIM to capture the current state live data of the actual data center can then be used to simulate and predict, visualize and quantify the impact of any change in the data center prior to implementation to mitigate the risk of disruption or failure.

“With the availability of real-time data from all the major components in the entire ecosystem and a system with machine learning algorithm in place, the data center could learn the optimum temperatures at different times of day and at different IT utilization levels and automatically adjust the cooling systems accordingly.”

Furthermore, it would keep track of the data and continually refine the algorithm to make it more effective over time.

As data centers look to become more automated and the industry aims towards remotely operated ‘lights out’ facilities, digital twins embedded into DCIM will become an imperative.

“A DCIM offering is not being used to the full extent of its powers if it is not being used to simulate and moderate the infrastructure running the data center, and a piece of infrastructure is no longer just a box on a drawing; it's a box that has data and shows wear and tear in equipment, which helps with planning, maintenance or replacement,” adds Oliver Goodman, head of engineering at Telehouse Europe.

“By pulling real-time data into that model such as the loads in each rack and how the cooling system is operating, you can use the DCIM combined with additional software to evaluate elements like air-flow and cooling demand, to run multiple ‘what-if' scenarios and understand their impacts in real-time.”

Still early days for digital twins in the data center space

Digital twins are still a nascent technique, and especially so in the data center space.

Though the numbers vary depending on the research firm, the digital twin industry is estimated to be somewhere around a $5 billion market in 2020 but expected to reach anywhere from $50-100 billion before the end of the decade.

“Digital twins are being used to create accurate 3D models of new constructions and projects but the level of detail that gets built into that model does vary from company to company,” says Goodman.

“While a significant cost, it effectively allows you to walk the building without actually being in the building. The benefits are obvious from a design, coordination and clash detection perspective. The possibilities of what you can simulate with these models is seemingly endless but few are using digital twins and BIM modeling to this full extent at the moment.”

There are a growing number of companies providing digital twins services. A few, such as Future Facilities, provide dedicated data center solutions. Japanese construction firm Komatsu, Sony’s semiconductor unit, and telco/data center firm NTT Docomo recently announced a new joint venture known as Earthbrain to ‘support digital transformation in the construction industry’ through digital twins.

A number of DCIM vendors are embedding the technology into their solutions.

“The technology exists,” says Ali Nicholl, head of engagement at digital twin specialists Iotics, “but the drive to adoption is inhibited by a focus on standardization and centralization, which increases costs and complexity of implementation.”

Ken Smerz, the CEO of 3D design and modeling firm Zelus, adds that a primary barrier to adoption has been a general hesitation to embrace advanced technology as a whole in the construction industry, something that has started to shift in the last 18 months.

“Digital twins are the main game changer,” says Maciej Mazur, product manager for AI/ML, Canonical. “They have reached maturity, and some DCIM vendors already embed digital twins into their products. In the next three years, we will likely see every data center modeled this way.”