The battle for space is being waged on the ground. As more and more countries and corporations find reasons to send satellites into our skies, a fight is underway to win the business of connecting the systems back down to earth.

Traditionally, ground stations have been run by the major satellite companies like Inmarsat and Iridium, or by countries like the US. Satellite operators have to either build their own stations, or lease antennas at the site.

That could change, with Amazon Web Services hoping to mirror the success it has had with the shift from enterprise data centers to the cloud by renting antennas out to users by the minute. This Ground Station-as-a-service, the company claims, could save users up to 80 percent of the costs.

Follow the cloud

“It's actually striking to me how similar this is to the cloud adoption of years ago,” Shayn Hawthorne, AWS Ground Station general manager, told DCD.

“In those days, you had start-ups where maybe they had no [data center] capability, and thus it made it very easy for them to jump into the cloud. But you also have some established, really capable customers who built their own on-premises capabilities, but used cloud for extra capacity.”

He expects the same to happen with Ground Station, where satellite start-ups like Myriota and Capella Space will use AWS for most, if not all, of their connectivity needs. Larger, established - but unnamed - satellite companies are equally “looking at using AWS Ground Station as dynamically scalable, extra capacity to support new needs that they didn't plan when they originally built their architecture,” Hawthorne claimed.

In May 2019, AWS launched ground stations in Ohio and Oregon, and followed up with a site in Bahrain in November. It expects to operate 10 such sites by the end of the year. “And that's going to give us the ability to have downlink capabilities in the European area, in the Middle East, in the African area, Southeast Asia, Asia proper, Australia, and then South America, and then back to the United States,” Hawthorne said.

Once data is received by the ground station, it is sent to nearby AWS data centers that are at most 9.5 milliseconds away, he said. Theoretically, that’s up to 2,000km (or 1,200 miles) away given light travels 200,000km per second in glass fiber - but fiber is generally not deployed in uninterrupted straight lines. “So we're close enough to our data centers that we have sub-WAN latency getting into each of the regions that our ground stations are connected with. We do a little bit of Edge processing, and then we get that data into the cloud.”

That cloud is, of course, Amazon’s own - its push to dominate the ground station market is directly tied to its cloud service. “You can log into AWS and you can actually get to our ground station console,” Hawthorne said. “And then you can start to do an onboard depending on if you have a satellite or a space data processing capability.”

The GS service directly transfers data into an AWS S3 bucket, Hawthorne said. “A customer can always then move it out of AWS to anywhere they want to go. But it's going to start by going through an antenna into AWS, like any other service.”

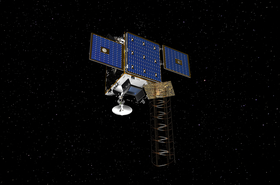

While Hawthorne would not discuss it, AWS GS is almost certainly tied to another vastly ambitious effort by Amazon to control the global network: Project Kuiper. Led by Rajeev Badyal, previously VP of satellites at SpaceX, Kuiper aims to operate some 3,236 satellites that offer high-speed broadband connectivity to the earthlings below.

The Kuiper System will “leverage Amazon’s terrestrial networking infrastructure to deliver secure, high speed, low latency broadband services for customers,” an FCC filing states. But to reach the terrestrial infrastructure of AWS data centers and fiber investments, Kuiper will use “Gateway earth station sites distributed throughout the Kuiper System’s service area.”

Technically, the filing could be talking about a different set of sites, but that seems unlikely. The only snag, currently, is that AWS GS only supports X-Band, S-Band, and UHF band frequency - while Kuiper will use Ka-band.

“We work in three specific frequency bands that the low earth orbit small sat CubeSat customers focus on right now,” Hawthorne said. “These are the common bands for a lot of the new start-ups and innovative systems that are being built by a bunch of companies that are funded by venture capital, both in the US as well as in Europe and in Asia.”

Hawthorne declined to comment on when GS will support Ka, only noting that “we’re willing to look into integrating feature frequencies for customers based on their needs.”

With the larger satellite companies like Iridium and Inmarsat using L-Band, “we would try to figure out how to put those types of antennas in to meet their needs as well, if we had customers who wanted it. As customers come in with other bands, we will move into that. I can even see in the future us someday supporting other types of communication mechanisms like Optical RF.”

Antennas form another battleground for Amazon, its competitors, and its customers. The company is currently building out the ground stations in partnership with defense contractor Lockheed Martin, but Hawthorne was keen to note the partnership was far from exclusive, and likely to be changed should superior antennas be found.

“We initially began collaborating with Lockheed Martin because we're very interested in many different types of antenna technologies,” Hawthorne said. “We're very interested in meeting with a number of companies in order to come up with the most cost-effective, but maximum capability, antennas we can get, because right now we will have hundreds of antennas after installing them at our ground stations for the next ten years.”

Parabolic antennas at the moment require individual antennas to communicate with individual satellites. “If we can instead move into some antennas that allow you to use one antenna to communicate with multiple satellites at the same time, then it will really help us.”

Hawthorne added: “And so we don't have any limits - except for the physics of communicating with each satellite, one at a time from each antenna.”