It used to be so easy.

Intel is not a cooling company, and it doesn't want to become one. But the company is being forced in that direction by the rapid rise of its processors’ thermal design points.

The chip company has become increasingly concerned that tomorrow’s chips will overload tomorrow’s data centers, and is researching how it can help.

"We want to be ready: As processor power keeps on increasing, the cooling challenges grow exponentially," Intel supercompute platforms group principal engineer Tejas Shah explained. In response, Intel is trying to upend data center cooling.

Increasing power densities have pushed developers to use immersion cooling, and some are looking at two-phase immersion where boiling fluids remove even more heat. Shah is leading an effort to these systems with ultra-low-thermal resistance, coral-shaped heat sinks integrated with a 3D vapor chamber cavity.

The project was one of 15 chosen by COOLERCHIPS, a program to dramatically change how data centers are cooled, run by the US ARPA-E (Advanced Research Projects Agency-Energy).

But before we get into the tech, let's address the elephant in the room: Two-phase immersion fluids have proven controversial: "We are not developing the fluid, we will be using industry-standard fluids," said Shah.

"We are very aware of the issue with all the PFAS and the regulations surrounding it," he admitted, referencing the toxic 'forever chemicals' used by most two-phase solutions. "3M are basically exiting the business of two-phase immersion; we are working with some of the fluid vendors."

The other issue is the global warming potential (GWP) of many of the fluids, which might outweigh any energy efficiency savings that immersion may bring. "Getting the PFAS out is the biggest challenge, but we are pretty confident we can meet the GWP requirements," Shah said.

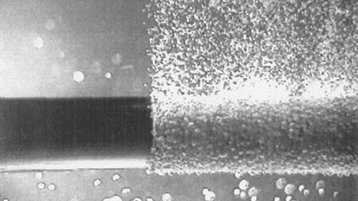

Back to the tech, the company is building coral-shaped heatsinks using additive manufacturing, aka 3D printing.

"It's basically optimizing the design to follow a specific mathematical function," Shah said. "So it's topology optimization - it's an iterative mathematical procedure to optimize for a certain cost function, whatever that is. In this case, it's reducing the thermal resistance and making sure that we hit the right hotspots."

The heatsinks are coupled with 3D vapor chamber cavities: sealed, flat metal pockets filled with fluid, to spread the boiling capacity of the two-phase system.

"The coral shape is increasing the surface area, but we also want to reduce the spreading resistance, which is why you have an embedded vapor chamber inside the 3D structure," Shah said.

When current flows through a semiconductor material, it encounters “spreading resistance” where the electrons spread across a wider area than initially anticipated. Lowering a chip's temperature helps reduce the spreading and, therefore, the resistance.

The new approach also uses an improved coating which enhances boiling by promoting nucleation. "So pretty much it helps with the boiling happening at the surface," Shah said.

With the three approaches combined, the company can cool processors all the way up to a thermal design point of 2kW. This is beyond what is on the market today, or likely to come out over the next few years, although Nvidia’s Grace Hopper Superchip has a TDP of 450W to 1kW by combining a CPU and GPU.

The immersion system can support "at least eight processors" consuming 2kW each, Shah said. Increasing the number in a rack further becomes more of a power limitation than a thermal one, he said.

While tests have proved promising, overcoming every issue is not a foregone conclusion - especially if the immersion sector can't get past the PFAS problem (vendor ZutaCore says it will eliminate PFAS in 2026, but has yet to provide specifics, while rival LiquidCool is diversifying into single-phase immersion).

"It's not a slam dunk, it is very challenging," Shah said of the project and Intel's other efforts. "But the whole goal is to reduce the thermal resistance and target the next generation of processors with the best thermal solution out there."

If it does work, however, Intel could find itself in the interesting position of being a cooling vendor. "What we might end up doing - it's a big might - but we might even sell the thermal solution with the processor initially," Shah said.

"That will build the ecosystem, and then the next generation might catch up to our processors."