There is a place in Colorado, overlooked by the Boulder County Mountains, where scientists gather to study the disastrous reality of our melting ice caps and glaciers.

The National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) monitors all the world’s natural ice and observes as climate change slowly eats away at that supply. Colorado is one of the most central states in the US, but even from there the impact that climate change is having on our oceans and our coasts is obvious.

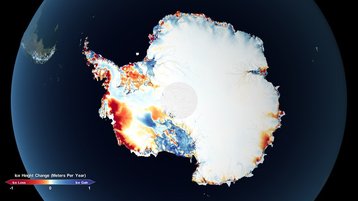

This is captured through satellites - in the obvious sense that we can see the square footage of our ice caps reducing through images, but also via altimeters which send down a pulse of light or microwave which is then returned back, and through the speed and distance, the size of the ice mass can be quantified.

As the ice reduces, we are slowly submerging or destroying the coastline. And there’s a less obvious effect: the digital infrastructure that lives there is at risk.

This feature appeared in Issue 50 of the DCD Magazine. Read it for free today.

Who forgot the ice?

“Temperatures are rising, and that has two primary effects in terms of sea level,” Walt Meier, senior research scientist at NSIDC, told DCD.

“One is pretty huge, and that is simply the direct effect in which, as water warms, it expands. That alone accounts for around a third of sea level rise so far,” Meier explained. “The other aspect is melting land ice. It runs off into the ocean, which is about two-thirds of the sea rise that we've seen.”

“The biggest effect is in coastal areas. The rule of thumb that I have heard is that for every foot of sea level rise, we lose about 100 feet of coastline - of beach. That depends on the type of coast - if it's cliffs then it won’t be as huge, of course.”

The implications of this rise on sea level are exacerbated and complicated by other factors, and there’s a specific part of digital infrastructure that is affected severely.

Most data centers are located further inland, but subsea cables and their landing stations, by their very nature, have no choice but to reside on the water’s edge.

Coastal erosion

“It should be fairly simple to know if [cable landing sites are] at risk or not, purely based on the sea level rise projection,” Dr. Yves Plancherel, a lecturer in climate change and the environment at Imperial College London told DCD during a particularly wet and dreary summer’s day in London, England.

“We just have to figure out the maps of where these installations are, and then we can apply estimates of sea level rise for the next 50 or 100 years and quite easily see if they are within predicted flooding zones or not,” explained Plancherel.

“But of course, what's difficult is that the coastline can change quite dramatically if you increase the [sea] level depending on whether the coastline is rocky, or sandy. Somewhere sandy is going to be very dynamic, whereas if it's a sheer cliff or rock, it will probably be less sensitive.”

In terms of protecting our coasts, there are steps that can be taken. The UK Department of Environment, Food & Rural Affairs announced in 2020 that it would be investing £5.2 billion ($6.33bn) in flood and coastal defenses between 2021 and 2027 including nature-based solutions and sea walls.

The US government in April recommended $562 million in funding for nearly 150 flooding resilience projects across 30 coastal states and territories, while the Climate Conservation Corps is expected to help protect the coast.

But when it actually comes to reinforcing our coasts, those developments have unintended ripple effects.

“Coastal erosion is something that's much more risky. You can have coastal engineering, to some degree, but you can end up causing damage as we're talking about changing global coastlines,” said Plancherel.

“There's going to be a competition for what you protect and the winning side gets to protect its assets. But at the same time, there are consequences. If you protect one part of the coastline, you can severely affect the erosion next to where you protected that asset.”

It is impractical to protect the entire coastline - thus decisions have to be made, and money invested in the problem.

A sandy problem

In South America, there have been cases where beach erosion has been so bad that the subsea cables buried below have actually been exposed.

Elena Badiola, product manager for dark fiber, colocation, and subsea services at Exa Infrastructure told DCD that in Argentina she had had to move a subsea cable manhole inland as it was close to exposure due to the amount of erosion.

“You have to go and re-bury them deeper in the beach,” Badiola said. “Because, once the cable is exposed, it's much easier for it to have an outage.”

Subsea cables are expensive and long-term projects - Google’s Equiano cable cost $1bn and took around three years to deploy - so operators have to think about climate risk in the years ahead.

“I think that environmental permits are getting more restrictive and more thorough, mainly because of this,” Badiola said.

“There are many circumstances that are taken into account now that weren’t 15 or 20 years ago. The stakeholders have to think - how is climate change or erosion going to affect these beaches in the next 25 years? It’s a very long time, and even scientists don't really know how climate change is going to affect them because it has been happening faster and more severely than their forecasts were suggesting.”

Those permits have to come from the local authorities - which is in itself a complicated issue as much of a subsea cable will be deployed in the “high seas,” space beyond territorial waters.

The longevity of subsea cables

Earlier this year, the International Cable Protection Committee published Submarine Cable Protection and the Environment, a paper written by marine environmental adviser Dr. Mike Clare.

Through his research, Clare identified a clear pattern of climate change wreaking havoc on our subsea cable networks - not just predicting damage in the future, but giving concrete evidence from the past.

A sediment flow in deep-sea Congo Canyon traveled over 1,000km, breaking cables connecting Africa. In 2017, Hurricane Irma’s floodwaters cut off power, submerged terrestrial data cables, and damaged landing stations across the Caribbean. Cyclones in Taiwan severed subsea cables in 2009, and storm surges in New York broke down Internet connectivity in 2012.

These are perhaps the more extreme incidents that come to mind when we think of climate change, but Clare also saw this pattern extend to more gradual and granular impacts that we would usually disregard.

Human activities such as fishing and ship anchoring remain the primary cause of subsea cable damage and outages - which happen somewhere between 200 and 300 times each year.

Planning cable routes to avoid fishing areas is part of the surveying process before cables are deployed, but even with this consideration it is still a notable problem, and perhaps one that we can expect to get progressively worse.

Ocean acidification (caused by the ocean absorbing carbon from the atmosphere), warming waters, unpredictable weather, and overfishing have been gradually driving fish into deeper waters. Waters where existing cables weren’t planning for that disruption, aren't as protected and will be more at risk.

Then there are the terrestrial cables that are close to the coast but definitely not designed for subsea conditions.

A 2018 paper projected that by 2030 - just seven years in the future - rising sea levels would submerge thousands of kilometers of onshore cable not designed to get wet. Similarly, cable landing stations also face flooding they were not designed for.

A diversity of geography

Sea level rise is not anticipated to affect the planet universally. Some areas are going to be more impacted than others, and some locations may even see the sea level fall, particularly those in a higher latitude such as Alaska or Norway where continents can “continental rebound” as the ice sheets break down.

But those regions that are more at risk include the Gulf of Mexico, Northwest Australia, the Pacific Islands, Southeast Asia, Japan, and the Western Caribbean.

The Under-Secretary-General for Legal Affairs and United Nations Legal Counsel - Miguel de Serpa Soares, has also noted that “low-lying communities, including those in coral reef environments, urban atoll islands and deltas, and Arctic communities, as well as small island developing States and the least developed countries, are particularly vulnerable.”

A location that falls at the perfect epicenter of these risk factors is the Maldives.

Sitting in Southeast Asia, the Maldives is comprised of around 26 atolls and its ground is an average of just 1.5m above sea level.

Imperial College London’s Shuaib Rasheed used satellite imagery to map the islands and found that the geography of the nation was undulating, like a living and breathing being, even on a relatively short-term basis.

“The effect of increasing sea level on the sediment balance in the Maldives is that you can actually see some islands grow, and some shrink. It's a very specific case, being that it is made up of coral atolls. But the complexity of the island is that it depends on a sand budget for existence - on how much sand is imported by the ocean or is exported,” Plancherel explained of his colleague’s research.

It seems an impossible feat to engineer a coastal digital infrastructure that can bend and sway with the rhythm of the islands.

Yet, earlier in 2023, a subsea cable landed on the island of Hulhumalé in the Maldives.

DCD reached out to Ocean Connect Maldives (OCM) to find out what measures were taken to ensure the longevity of their subsea cable and landing station.

“Coastal erosion and rising sea levels are very big concerns. That is why we had chosen Hulhumalé, an island entirely built on artificial land,” an OCM spokesperson said.

The island of Hulhumalé was designed.

According to OCM, Hulhumale was created to have “eco-friendly initiatives” such as building orientations that reduce heat gain, streets with wind penetration optimization, and amenities within walking distance to reduce the need for cars. But, perhaps most notably, it has an average height of 2m above sea level - just that little bit more than other islands in the Maldives, reducing flood risks.

OCM has put all of its equipment at the landing station on the first floor - just in case there is a flood.

The landing station itself is located around 200m away from the beach manhole. It is here where the data center and operational offices also reside.

“OCM’s Network Evolution Plan (NEP) is done annually for the next five years,” the company said. “Climate change is a slow-moving and long-term global issue with far-reaching impacts. Therefore, we incorporate climate change forecasts and considerations into the NEP processes.”

Beyond that, the company and the government conduct ongoing analyses of the sea and coastal geography of the island, with OCM noting: “The Maldives, including Hulhumalé, is particularly susceptible to the impacts of climate change, including rising sea levels, coastal erosion, and changing weather patterns.”

Part of the problem, or the solution?

Our subsea networks are a victim of the problem, but they are also a contributor - as is every industrialized sector.

Nicole Starosielski, author of The Undersea Network and subsea cable lead principal investigator for Sustainable Subsea Networks, evaluated the sustainability of subsea cables, while acknowledging the difficulty that Sustainable Subsea Networks has had in actually quantifying the sector.

“It’s a difficult process, generating a carbon footprint of the [subsea cable networks] industry. Unlike a data center which has four walls where you can draw your boundary, the cable industry is comprised of so many elements - from the landing station to the cable itself,” said Starosielski.

“There are all these other pieces that the industry is trying to account for. One is obviously the marine sector. You have a fleet of ships that are older, and there's not a lot of margin in the marine sector. You don't see a lot of extra cash to build new ships.”

The lack of cable ships is a notable issue for the subsea network - in part due to the long wait times for deployment, but also because these older ships tend to be worse for the environment. As of 2022, of the roughly 60 cable ships in working order, most ships were between 20 and 30 years old, 19 were over 30, and one was over 50.

“They're [cable ship companies] trying to modernize and upgrade their fleet but they don't have the money funneling in like it is in the data center world. Cable ships have not transitioned to net zero but, then again, the whole shipping industry hasn’t. They're working on it - the International Maritime Organisation has a lot of efforts underway, but there remains this problem that the infrastructure needs to be updated.”

Beyond the ships themselves, the materials used in the cables should be considered. While, once decommissioned, materials like copper can be recycled, the process of acquiring enough high-quality copper or steel can have a knock-on effect, based on the supply chain in various locations, e.g. the Nordic versus China.

The quality of the materials and the cables themselves can have a long-term impact on the cable's ongoing footprint. If the cable needs regular repairs, each repair is just another hit to the planet - and the cable owner’s wallet. But, again, more armoring means more steel.

Similarly, avoiding fishing locations and attempting to reduce the risk factors for damage increases the length of the cable and thus the need for materials.

The sustainability of our subsea networks - both in terms of their impact on the environment and their longevity in the face of climate change is a long-winded conversation of compromise and adaption.

But, as with any issue, the more data we have, the better we will be able to tackle it. That’s where we come back to initiatives like the NSIDC. The more accurate visualizations they provide of the state of our planet in the next 10-30 years, are the basis for ensuring our subsea network will be sustainable and resilient.