Plenty of data centers use solar power. Apple has been buying it up wholesale, Foxconn has been using it to power containers, and NGD claimed a roof-full of panels could cut its PUE to a perfect score of 1.0. But do the numbers really add up?

Alongside the positive stories, there has been some skepticism. One particular commentary “I Love Solar Power But…” from James Hamilton, data-center guru plus vice president and distinguished engineer at Amazon Web Services, back in 2012 is still making waves today. In his post Hamilton asked serious questions of Facebook, Apple and other solar advocates.

Solar power reduction factors

“I love solar power,” wrote Hamilton, ”but in reflecting carefully on a couple of high-profile data center deployments of solar power, I’m developing serious reservations that this is the path to reducing data center environmental impact.”

Hamilton’s primary concern was and still is the way solar-array power capacities are advertised. All too often, reports simply quote the maximum output of a solar array, without taking into account two real-world variables which reduce the array’s capacity.

A solar panel gives maximum output when directly illuminated, but in practice, sunlight will strike it at an angle, depending on the time of day, the time of year, and the location. At a higher latitude, solar arrays will give less energy. Similarly, the sun’s energy is dissipated by scattering in the atmosphere, which depends on the solar array’s altitude above sea level. Both these factors can be calculated by a tool on the web called the Solar Power Calculator. If they are not factored in, a solar array will have unrealistic capacity ratings.

Now, take Apple and Facebook…

Hamilton’s post got attention because he used Apple’s Maiden, North Carolina data center and Facebook’s Prineville, Oregon data center as examples. When Hamilton included the variables — location and altitude — in the capacity calculations, the output from the solar arrays at Prineville and Maiden barely made a dent in the power requirements for either data center. Regarding Apple’s Maiden data center, Hamilton’s calculations suggested a solar array which supplied all of the data-center’s power would have to cover over 4,000 acres.

Since 2012 things have obviously changed, and I was curious if Hamilton had any further thoughts. Via shipboard email, he wrote, “Both Apple and Facebook continue to invest in renewable energy, but it is still hard to fathom just how much space is required to fully power a large data center.”

It is evident that solar needs a lot of space: First Solar, a provider of photovoltaic solar energy solutions, affords us an idea with its California Flats solar project. The 280 megawatt solar array occupies somewhere around 2,900 acres in southeast Monterey County, California.

Hamilton brought up another interesting point about finances: “As I work through the numbers… they just don’t seem to balance out unless tax incentives are included. I’m not convinced having the tax base fund data-center deployments is a scalable solution. And, even if it could be shown that this will eventually become tax neutral, I’m not sure we want to see data-center deployments consuming hundreds of acres of land on power generation.”

A thought-provoking comment

Hamilton’s original post also generated some thought-provoking comments. “Hi, James – your analysis seems mostly correct, but I have an alternate proposal,” Dave Anderson responded on the blog. “Solar plus data center is not an answer to how I power my data center? It is an answer to the question: I just built this huge building, what do I do with the roof?”

If there is enough solar energy to make a solar array cost-effective, there are actually other benefits, argued Anderson. The panels will also shade the roof and reduce heat build-up — a win-win situation.

“In Dave’s approach, we don’t get a substantial change in the grid power consumption, but we reduce the heat load while getting 0.25 percent of the building’s power requirement,” responded Hamilton. “I think it could work. It’s worth thinking through more carefully.”

An example - Synergy Networks

I followed this thought on a recent visit to Fort Myers, Florida. One of my stops was Synergy Networks, a local ISP that also provides colocation and hosting services. My contact at Synergy did not know it, but I had an ulterior motive for my visit. Synergy Networks has a data center and a roof-mounted solar array.

On arrival, I was introduced to Ken Boyd, vice president of finance and business development. As Boyd explained the services provided by Synergy Networks, I realized the company was one of those rare full-service ISPs willing to take care of a customer’s every need, even sending technicians to clients if they need on-site help.

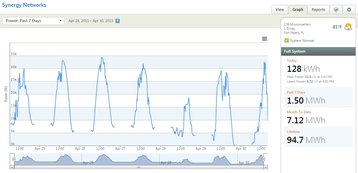

Boyd kept noticing my glances at the large conference-room monitor. It was tracking the solar-array’s performance shown to the left.

Figuring it out, Boyd hit a few keys on his notebook and brought up a picture of the building’s roof. It’s stuffed full of solar panels. The array consists of Trina Solar 60 cell, 250 watt, 15.6 percent maximum-efficiency panels that are wired together using micro-inverters and management software from Enphase Energy. The total array outputs 44 kW.

Is it cost effective? Boyd, being the finance person, started throwing numbers my way:

- An average week nets 1.5 megawatt hours from the array.

- The array replaces on average $500 dollars worth of grid electricity each month.

- The company expects a five-year payback.

The more Boyd talked about the company’s solar array, the clearer it became that this installation made sense. But Boyd agreed with Hamilton: solar-energy projects are not viable without incentives. In Synergy Networks’ case, the incentives amounted to the federal government’s Solar Investment Tax Credit and the Florida Power and Light (FPL) solar rebate.

Solar tax breaks

The federal tax credit amounts to a reduction of the organization’s tax obligation equal to 30 percent of the out-of-pocket cost of the solar system. Boyd mentioned applying for the tax credit was just a matter of filling out paperwork.

However, the FPL solar rebate is not quite that simple. At the designated time and date, the FPL solar-rebate application website goes live. Within seconds, those interested in getting a rebate start entering data as fast as they can, It is first come first served, and when the designated amount of money runs out, the site closes.

Boyd said he practiced entering the information just to make sure Synergy Networks’ application made it. The year Boyd applied (2013) the website closed after one hour. The 2015 rebate application was even more of a race. Alissa Jean Schafer, marketing and media director at US Solar Institute, said: “Residential solar rebate funds were all claimed or allocated within the first 30 seconds. Business solar rebates followed suit and were completely claimed in the next 3 minutes.”

It is easy to see why. With 75,000 dollars from the FPL rebate program and the federal tax credit, Boyd said the company’s payback dropped from 25 years to five years.

Commenting on the Synergy Networks installation, Hamilton said he still likes the idea of a rooftop solar array as an additive source of renewable energy: “It’s clearly a good business decision in many jurisdictions with favorable tax benefits, but it will not meet the total power needs of the facility.”

Intangible benefits

There are also intangible benefits from using a renewable resource such as solar power. It allows positive marketing, which Hamilton alluded to that back in his original blog post. Boyd agreed, telling me clients are impressed the company is dedicated to renewable resources.

It is also important to Synergy employees. “The fact that Synergy is helping reduce its impact on the environment by using solar power makes me proud to work here,” said Logan Tygart, senior system administrator. “It’s interesting to see how much electricity the array is producing at different times of the day.”

Mr. Hamilton asked us to mention that the opinions expressed here are his own and do not necessarily represent those of current or past employers.