The relationship between data centers and power capacity is increasingly tumultuous.

This is all the more notable in data center hotspots, such as Northern Virginia, Frankfurt, and Dublin. In the UK, London has faced a similar crunch.

The city has been plagued with power capacity concerns, with data centers often getting the brunt of the blame after house building in the west ground to a halt.

But the problem of power in the capital city is not one of simple causes and easy fixes. “You only need something to go slightly awry, and you will see a significant bump in the price of power,” says Wayne Mitchell, director of Dallington Energy consultancy.

“On the back of the Gaza and Israel situation, energy prices jumped 44 percent in the space of eight days [in the UK]. Similarly, on the other side of the world, workers at the Chevron liquified natural gas plants in Western Australia went on strike, and UK gas prices jumped 20 percent that day.”

Two years ago, Russia declared all-out war on Ukraine, and the impact on energy systems is still being felt in London’s energy systems, and across Europe.

With Russia as a major gas exporter for much of Europe, and the political chasm that the first day of invasion caused, many nations were suddenly in a position where energy prices skyrocketed, and supply was instantaneously very fragile.

The UK has, to an extent, found solutions to this energy crisis - but the costs are still felt by the populace, and the headlines remain.

With fragility comes insecurity, and the media has locked onto this in the last year - either warning the UK population of potential risks, or cashing in on drama by fear-mongering, depending on your point of view.

As power-hungry monsters, data centers are often at the forefront of conversations that warn of potential winter blackouts and power provisioning issues. Data centers are held to blame for reports that they have taken power that could have gone to houses.

Winter blues

This winter and last, we have wondered if our power system will make it through the dark season. Of course, London is not alone. The whole country gets cold, and shares one national transmission grid.

In 2022, several media outlets reported that the UK could expect to see blackouts during particularly cold periods (we didn’t), as a result of a carefully edited quote from National Grid’s CEO John Pettigrew, who was talking about a truly worst-case scenario in which everything went wrong, all together, simultaneously.

2022 was more precarious than this winter is set to look (though the energy system remains ever-tempestuous and easily aggravated) but according to Mitchell, country-wide blackouts were never really a serious concern.

“Blackouts are the very last thing that is going to happen when you look at the long hierarchy of actions laid out by the Electricity Supply Emergency Code (ESEC),” he explains.

The ESEC is a backstop piece of legislation that allows the grid operator to take emergency actions in those worst-case scenarios. Regarding the media frenzy John Pettigrew inadvertently kicked off, Mitchell points out that the ESEC only works with extensive risk assessments.

“As a grid operation, absolutely they should always be doing scenario planning, and doing really awful scenario planning. He was talking about the worst possible case, and people latched onto it.

“The word ‘blackout’ is really quite alarming if you don’t understand the network, and ultimately ten or twenty different outlets ended up putting the story on the front page.”

Blackouts are alarming to residents, but to data centers they can cause concerns on a par with a “security incident.”

Dallington Energy and Kao Data teamed up on a whitepaper this year to dispel some of the anxieties in advance, or as Mitchell puts it, to “introduce some rational thinking.” The ultimate message was that winter is nothing new, and the grid and our data centers will trot along quite comfortably.

The London Hot Spot

As is common worldwide, data centers in the UK seem to center around one particular location. In this case, it is London: specifically, west London.

This is for a variety of reasons. There are transatlantic cables that run from Cornwall to London through the M4 corridor, creating a well-connected digital highway that data center operators have taken advantage of, creating the well-known clusters - with Slough, the Docklands, Park Royal, City, and Isle of Dogs among them.

Beyond that, there is also the proximity to the capital. Some data centers can be spread further away from major urban locations, but some industry sectors, such as finance, rely on high-speed digital functions, so being close is a key advantage.

The way the grid works, however, means that this can cause some problems.

Power goes on a long and arduous journey before it reaches the end user. Originating at the power plant, it enters the National Grid’s transmission network - the high voltage network covering the entire nation. This then connects to the distribution network - the more local and lower voltage network, where electricity providers portion it off to their customers.

Controlling all of this is the Electricity System Operator.

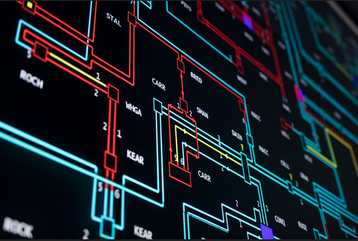

“The Electricity System Operator (ESO) has a National Control Centre, down in the southeast, which is basically a control room - it looks a bit like the NASA headquarters,” explains Paul Lowbridge from National Grid.

In that control room, the ESO has the entire electricity system mapped out, and can see what is being generated and where it's being used. The ESO’s job, then, is to make sure it runs smoothly.

“Part of it is ‘how does it all come together and make sure it's all balanced?’” Lowbridge says. “But then, within that, there will be particular constraints. In certain parts of the country, although balanced overall, they might need to make some adjustments about how power is flowing in and out of a certain region, or city, and then the distribution networks will have their eye on particular cities or locations.”

One such constraint might be the problem of having more than 100 data centers in one city’s boundaries.

“There was no thought or foresight in developing data centers around London,” Spencer Lamb, chief commercial officer of local data center operator Kao Data, says. “Because no one had any appreciation at the time - and rightly so - that they would eventually be consuming hundreds of megawatts of power infrastructure as they are today.”

Data centers have not only balooned in quantity and size but also in density. If the AI boom follows current industry predictions, data centers are only going to get more power-hungry. In other words, this problem is just going to get worse.

The logical thing to do would be, where possible, to build data centers away from London. “I think we need to locate data centers in locations that have the opportunity to get private energy production to them bypassing the distribution networks and therefore not paying that premium but also, in itself, it will enable development investment in renewables,” Lamb argues.

This would take some of the stress off of the power distribution networks in London, which are struggling with the weight of the Internet on their shoulders.

Home sweet home

In 2022, the Greater London Authority (GLA) published a document exploring the “West London Electrical Capacity Constraints,” which revealed that major London-based applicants (over circa 1MVA) to the Scottish and Southern Electricity Networks distributed network would have to “wait several years” to receive new electricity connections. This included housing developments.

Housing is, according to the GLA’s website, “the greatest challenge facing London today.”

The website goes on to say: “In recent decades, London has excelled at creating jobs and opportunities. But at the same time, we have failed to build the homes we need. Now a generation of Londoners cannot afford their rent and many are forced to live in overcrowded or unsuitable conditions.”

It is unsurprising, therefore, that in the wake of the Capacity Constraints document, an onslaught of news articles circulated, blaming data centers for a “ban” on housing developments.

The GLA document describes data centers as using “large quantities of electricity, the equivalent of towns or small cities,” while broadsheet The Telegraph nicknamed data centers “Energy Vampires.”

A spokesperson for the Mayor of London told DCD via email in July 2022: “The Mayor is very concerned that electricity capacity constraints in three West London boroughs are creating a significant challenge for developers securing timely connections to the electricity network, which could affect the delivery of thousands of much-needed homes.”

In an updated response from the GLA, the infrastructure policy lead Louise McGough told DCD that the issue remains a “vital” concern for London, but that in the immediate term, the plan is to “connect developments if they require under 1MVA of electricity annually (where they are not also facing distribution-level constraints), allowing many housing developments to progress that would otherwise have been stalled.

“While there remain challenges for schemes requiring higher electricity capacity, the solutions being pursued by the utility providers are encouraging and are a step in the right direction.”

DCD reached out to several housing associations but they did not provide comment.

Lobby group techUK in 2022 said some of its data center operator members were also finding it hard to get grid connections due to the first-come-first-served queue system. TechUK was in conversation with the GLA, attempting to find solutions to this problem, according to Luisa Cardani, head of the group’s data centers program. She told us that the local authority has heeded many of techUK’s suggestions.

One of the key recommendations made by techUK was to rethink the queue-style setup. “The connection queue was first-come-first-served, but following our recommendation, this has been changed, meaning they can get rid of what we call ‘zombie’ projects,” explains Cardani.

“Some [companies] - and we're not speaking on behalf of techUK members here - just hedge their bets. Some developers put numerous bids in for potential future projects and that would make it very difficult to then prioritize because it isn’t obvious how quickly they need that power.”

Shortly after the publication of the Capacity Constraints document, a freedom of information request was filed with the GLA requesting data/reports on the connection requests. The GLA declined to share, stating that the data is “commercially sensitive.” For the time being, it seems the companies behind those zombie projects will remain unidentified.

There are currently 400GW of connection requests in the queue, of which Ofgem reckons 60 to 70 percent will fail to materialize or connect. Some 57 percent of users (queue dwellers) have submitted multiple Modification Applications (i.e., they get to the front of the queue, but aren’t ready yet, so ask for more time).

In fact, according to Ofgem: “As it stands, if all connections in the current queue were to take place, this would enable more generation capacity than is anticipated to be needed to achieve a Net Zero power system by 2035, even under the ESO’s most demanding Future Energy Scenarios (FES) modeling scenario.”

Ofgem published its revised queue management system on November 13, 2023. The new system was set to kick off on November 27 and is hoped to speed up connections for viable projects and enable stalled or speculative projects to be “forced out” of the queue.

National Grid will have the power to enforce strict milestones for connection agreements, and the first terminations are expected to happen in 2024.

Also in November 2023, the UK government shared plans to invest £960 million ($1.1bn) in green industries and overhaul the country's power network.

The “connections action plan” is hoped to cut connection delays from years to just six months, and free up around 100GW of capacity, while the funding is going to manufacturing capacity in net zero sectors.

This is a semi-long-term solution, but in the meantime, National Grid has been working on short-term boosts to capacity in the region.

“There are potentially some quite technical options we [National Grid] can explore that would effectively allow those distribution networks to have more capacity available for some of the smaller connectors that at the moment are facing constraints,” explains Lowbridge.

“We think there are potential options to be explored around being able to release some more capacity on their networks by looking at some of the engineering assumptions we use at the boundaries between transmission and distribution.”

He continues: “There's a point where the transmission network links to the distribution network, and then the distribution network makes capacity available to the local network.

"There are two things going on. One is across all of the distribution networks throughout the country, we've been coordinating and looking at a solution called ‘technical limits,’ which is when you look at the engineering assumptions at that boundary. We think there are different formulas and models that can be used that would then release a certain amount of capacity for the distribution network in addition.”

Lowbridge estimates that this could free up around 30GW, a proportion of which could then be allotted to the distribution network operators (DNOs) in London.

“Then the second point is, again, still in that kind of relatively tactical space. We've been working directly with the GLA, SSE, and UK Power Networks to look at potentially increasing some of the technical boundaries that we use between the DNO and transmission in that area. We think that there is potential that it could make more capacity available for projects connecting at lower voltage levels,” he says.

“It's slightly early days to see exactly how quickly that can have an impact. But we expect over the coming months for that piece of work to start to show what can be made available, and we think there's potential there for that piece of work to help release some capacity in the London area."