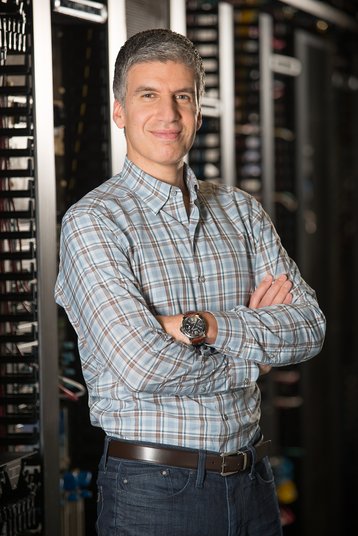

"The differentiation is not in the box anymore. Differentiation is around offering solutions that enable our customers to transform, to obtain cost efficiency and agility benefits of the cloud,” said Rami Rahim, CEO of Juniper Networks, in an interview with DCD.

Having obtained a Master's degree in electrical engineering from Stanford, Rahim joined Juniper Networks in 1997 as a specialist in ASIC design, responsible for the chips that powered the first products from the company which has become Cisco’s chief rival in infrastructure networking. Seventeen years later, he assumed the CEO’s seat, at a time when the networking landscape was going through considerable changes.

In the nineties, the telecommunications market was dominated by a handful of equipment vendors and expensive, proprietary technology was baked into silicon. It was in this environment that Juniper first challenged Cisco, and managed to carve out a respectable market share. More recently, breakthroughs in chip design and manufacturing have made it possible to deliver advanced networking functionality via generic switches and routers, manufactured in Asia at a very low cost, which meant innovation slowly moved into software.

It's not a secret that Juniper's previous CEO, Shaygan Kheradpir, was brought in to cut costs and improve the balance sheet in order to please activist investors. He succeeded in this mission, so Rahim could focus on one thing - making the most of software-defined networking (SDN).

"There is a mindset shift in the industry, where the perception of value is now transitioning from being purely embedded in hardware, to the software domain. And that, in my view, is absolutely positive, because it's in our best interest to monetize our differentiation, to monetize our R&D, commensurate with the way we invest," he said.

Under Rahim, Juniper virtualized its popular MX series routers and separated the JunOS network operating system – which saw initial release in 1998 – from the underlying hardware.

"We were the first established networking vendor to offer a completely disaggregated operating system model on third-party white box switches, and we've learned a huge amount by going first and deploying with our customers,” he explained.

"They want great levels of flexibility: they want to be able to choose the hardware and software capabilities that they need for their specific use cases. They want more network visibility, greater control, more programmability. And they want to have a more granular business model; in other words, they want to pay for what they actually use."

Open source challenger

In recent years, Juniper has also increased its participation in various open source initiatives. Some of its switches were made compatible with software from the Open Compute Project (OCP), and the company released the code to its SDN ‘meta-controller’ Contrail as open source; initially known as OpenContrail, the project has been rebranded as Tungsten Fabric and now sits at the heart of The Linux Foundation's new networking organization. In 2018, Juniper also joined the Open Networking Foundation, which counts some of the world's largest telecommunications providers among its members.

To Rahim, this is a natural extension of the company’s strategy: "As a challenger in this industry, we have always viewed openness as fundamental to our success. As a challenger, openness is your friend."

Juniper was, at one point, famous for paying software engineers some of the highest average salaries in Silicon Valley. Today, the company continues this tradition, spending more than 80 percent of its R&D budget on software. And the focus on software has pushed it further into the cloud market, where hardware has been commoditized, and software reigns supreme.

"Cloud has very specific meaning for each of our different customer segments - it is still the architectural and service delivery approach that is fueling the growth and the business momentum of the big cloud providers,” he said. "Cloud is also the underlying architecture for all future telco delivery models. 5G, in and of itself, is not going to justify the investment that's required to enable it. It's going to require new services, and so 5G is going to usher in new services that I think are going to make telcos more successful than they have been in the past. And those services are all going to be cloud-native.

"And last but not least, on the enterprise side, cloud is the thing that's top of mind for each and every one of the CIOs that I talk to - it's all about moving workloads and applications to a multi-cloud environment, and reaping the cost and agility benefits of this approach. Cloud is a theme: it has been a theme for the last couple of years. It will continue to be a theme in 2019, and a few years to come.”

Perhaps the most serious change to affect Juniper in the past few years is the change in its customer base: the company originally focused on the telecommunications market, then the enterprise sector. Today, it counts hyperscale data center operators among its most valuable clients.

These organizations are running some of the largest server farms in the world, but their very size presents an inherent risk - if the relationship goes well, the supplier could shift hundreds of thousands of products at the stroke of a pen. But if it then goes sour, the supplier will see their revenues decimated in an instant.

"We understand the hyperscale market very well - depending on the quarter, roughly around a quarter of our revenue comes from cloud providers; that includes hyperscalers, but also many smaller cloud and SaaS providers throughout the world,” Rahim said.

"We understand what hyperscale customers require through practice, through years of engagement with them on a very technical level. We understand what they are looking for in terms of performance, reliability, flexibility, visibility and telemetry. All of those lessons have fed into the technology that we have developed, and the roadmap that we will be introducing to the market that really caters to the hyperscale space."

No worries

The situation with hyperscalers is made worse by the fact that these companies have enough resources to develop their own networking kit – examples include Facebook’s switches like the Wedge and the Backpack, and LinkedIn’s Pigeon. However, Rahim is not worried that his current customers will dump Juniper kit (or software) to adopt their own, in-house creations.

"The folks that work for hyperscale companies, the network operators, the engineers, are extremely talented. In some sense, you are competing with them - you need to demonstrate to them that the capabilities that you are introducing to the market are ahead of not just of you peers, but - for specific use cases - ahead of what they themselves can develop and implement," he explained.

"I don't think they want to get into the business of developing networking infrastructure, networking equipment, just because it's fun to do so - they will only do it if they believe they can't get the technology that they need elsewhere.

"As long as we apply the right sense of urgency and speed to the kinds of technologies that they care about, we will continue to have a very big role to play in building out the large hyperscale networks around the world."

And finally, our conversation turned towards China. Incumbent networking vendors in the US and Europe are currently fighting off a two-pronged attack. On one side, they are squeezed by the white box, ‘no name’ manufacturers that are fully invested in the meaning of commodity and compete not on features, but on price. On the other side, firms like Huawei and ZTE are constantly improving their game, and have started offering levels of aftermarket service that can match their Western counterparts.

"The technology coming out of China has been increasing in capability, increasing in sophistication, for a number of years now - I don't think that there's anything new that happened recently that causes us to be more or less concerned than we have been in the past,” Rahim told DCD.

"I abide by the notion that 'only the paranoid survive.' I tend to take all of my competitors worldwide very seriously - this is, at the end of the day, a very competitive industry. But ultimately, what I focus more on are my customer requirements, and how we get to solving for those requirements with truly differentiated technology.”

"It comes back down to the fact that I think the differentiation is not in the box anymore.”

This article featured in the February issue of DCD>Magazine. For more information, or if you'd like to subscribe for free, click here or fill in the form below