Since it was first proposed by Christian Belady and Chris Malone and promoted by the Green Grid in 2006, power usage effectiveness (PUE) has become the de facto metric with which energy efficiency of data centers are measured.

It is easy to calculate – a ratio between total facility power and power consumed by the IT load – and it provides a simple single metric that can be widely understood by non-technical people.

But as leading facilities move to PUEs below 1.1 and more companies look to achieve carbon-neutral status, it’s time to ask; should we move on from PUE? And if so, what to?

PUE: a victim of its own success

In a perfect world, PUE would be 1; every kilowatt of energy coming into the data center would be used only to power the IT hardware. And while a perfect 1 is likely impossible, being able to quickly and easily measure energy use has driven improvements.

The Uptime Institute says the industry average for PUE has dropped from around 2.5 in 2007, to around 1.5 today. But even Uptime has said the metric is looking ‘rusty’ after so long.

“PUE has been one of the most popular, easily understood and, therefore, widely used metrics since the Green Grid standard was published in 2016 under ISO/IEC 30134-2:2016,” says Gérard Thibault, CTO, Kao Data. “I believe that its simplicity has been key, and in many respects, customers use it as a metric to evaluate whether they are being charged cost-effectively for the energy their IT consumes and how sustainable they are.”

“In an industry that is somewhat complex, PUE has become accepted by customers as a clear indicator of energy efficiency, becoming inextricably linked to sustainability credentials.”

However, after more than a decade, PUE could be starting to become a victim of its own success, argues Malcolm Howe, Partner at engineering firm Cundall, whose data center clients include Facebook.

“PUE has been an immensely beneficial tool for the industry. And in the guise of the role that it was originally intended for it has driven very significant improvements in energy efficiency in data centers,” he says.

“People can quite readily get their heads around it on a very superficial level, but it's got loads of things wrong with it when you get below the surface.”

The limitations of PUE

As we near the limits of what conventional cooling can achieve and data center owners and operators look towards carbon neutrality or even negativity, PUE starts to lose its value as a metric.

Some of the most efficient data centers are starting to achieve PUEs of 1.1 or lower; the EU-funded Boden Type data center in Sweden has recorded a 1.018 PUE, while Huawei claims its modular data center product has an annual PUE of 1.111. Google says its large facilities average 1.1 globally but can be as low as 1.07.

As facilities become more efficient, measuring improvements with PUE becomes harder and gains become increasingly incremental.

“We're now down to PUEs of 1.0-whatever; we need more precise methods of measurement,” says Howe. “We're focused on trying to achieve these sustainability targets and net-zero, and we're doing it with a tool that is a blunt instrument; we're using a metric that doesn't really capture the impact of what's going on.”

An example of its bluntness is that PUE doesn’t capture what is happening at rack level. IT power to the rack can power rack level UPS or on-board fans; energy that could and probably should be added to the debit sheet, yet isn’t.

Howe notes that in a conventional air-cooled rack, as much as 10 percent of the power delivered to the IT equipment is consumed by the server and PSU cooling fans. Some companies can make their PUE look better this way in what he describes as “creative accountancy.”

“Not all of that power is actually being used for IT. And I think a lot of people lose sight of that,” he says. “A lot of model operators putting UPS at rack level; they can immediately make their PUE look better by shifting the UPS load out of the infrastructure power and putting it into the IT power. You're just moving it from one side of the line to the other, you haven't actually changed the performance.”

PUE a marketing metric

Howe also notes that PUE’s simplicity and widespread use across the industry has led to it being used as a competitive advantage weapon as much as an internal improvement metric.

“Over time it has been seized upon as a marketing tool,” he says. “Operators are using it to bring in customers, and customers are going along with that and giving minimum PUE standards in the RFPs.”

Many operators will happily tout the PUE of their latest facilities, and use it as a lure for sustainability-conscious customers.

“PUE was never really intended for that, it was always an improvement metric,” He says operators should “measure the PUE, implement changes, and then measure it again to assess the effectiveness.

“It’s taken on an importance and a profile within the industry that was never intended, for which it's not really suited.”

Liquid cooling and PUE

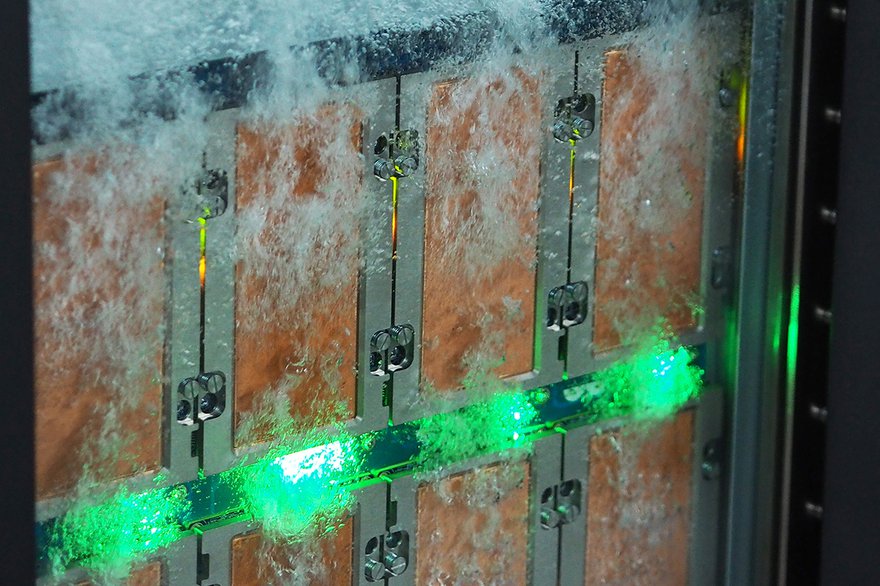

As we reach the limit of air cooling, liquid cooling is becoming an increasingly popular and feasible alternative. But as adoption increases, the utility of PUE as a yardstick lowers.

“Even if you had a perfectly efficient fan motor, it is going to consume power,” says Howe. “We've got to the limit of what is achievable within the physics of what we've been doing with air cooling.”

In an opinion piece for DCD, Uptime Institute research analyst Jacqueline Davis recently warned that techniques such as direct liquid cooling (DLC) profoundly change the profile of data center energy consumption and “seriously undermine” PUE as a benchmarking tool and even “eventually spell its obsolescence” as an efficiency metric.

“While DLC technology has been an established yet niche technology for decades, some in the data center sector think it’s on the verge of being more widely used,” she said. “DLC reshapes the composition of energy consumption of the facility and IT infrastructure beyond simply lowering the calculated PUE to near the absolute limit.”

Davis noted that most DLC implementations achieve a partial PUE of 1.02 to 1.03, by lowering the facility power. But they also reduce energy demands inside the rack by doing away with fans - a move that reduces energy waste, but also actually makes PUE worse.

“PUE, in its current form, may be heading toward the end of its usefulness,” she added. “The potential absence of a useful PUE metric would represent a discontinuity of historical trending. Moreover, it would hollow out competitive benchmarking: all DLC data centers will be very efficient, with immaterial energy differences.”

“Tracking of IT utilization, and an overall more granular approach to monitoring the power consumption of workloads, could quantify efficiency gains much better than any future versions of PUE.”

TUE: the new PUE or one metric among many?

If PUE really is too long in the tooth, is there a ready-made replacement that has the simplicity of PUE but can provide a better picture?

Howe says Total-Power Usage Effectiveness (TUE) can be a more effective metric at calculating a data center’s overall energy performance. TUE is calculated via IT Power Usage Effectiveness (ITUE) x PUE. ITUE accounts for the impact of rack-level ancillary components such as server cooling fans, power supply units and voltage regulators. TUE is obtained by multiplying ITUE (a server-specific value) with PUE (a data center infrastructure value).

“ITUE is like a PUE at rack level and addressing what is going on in a way that PUE on its own does not. It's saying this is how much energy is going to the rack; and this is how much of that energy is actually going to the electronic components,” he says.

“It's giving you a much more precise understanding of what's going on that level; which is you've either got some serving server fans spinning around or you've got some dielectric pumps, or you've got something else which may be completely passive.”

TUE and ITUE aren’t new; Dr. Michael Patterson (Intel Corp.) and the Energy Efficiency HPC Working Group (EEHPC WG) et al proposed the two alternative metrics around a decade ago.

Compared to PUE, TUE’s adoption has been slow. The equations aren’t much harder to calculate, but TUE requires a greater understanding of the IT hardware in place – and that is something that many colo operators won’t have a lot of visibility into.

Howe says Cundall is starting to have conversations about TUE and moving on from PUE with its customers partly as it looks to ensure all its projects are heading towards net-zero carbon, but also as customers look to achieve their own sustainability goals.

As more companies look to deploy liquid cooling – which takes efficiency beyond PUE – more companies may opt for TUE as a way to better illustrate their sustainability credentials amid a landscape where most facilities operate at PUEs in the low 1.1s.

“Operators are going to want to try and position themselves as being ahead of the game and doing more and achieving more. Previously, people have been comparing each other using PUE, but you might now get companies saying ‘my TUE is X’.”

PUE & TUE; just parts of a wider sustainability picture

While TUE can provide a more granular view of energy efficiency, even then it is still just one part of the total sustainability package. There is no one metric to capture the entire picture of a data center’s sustainability impact.

Many of the large operators now offset their energy use with the likes of energy credits and power purchase agreements to ensure their operations are powered directly by renewable energy, or at least matched with equivalent energy contributing to local grids.

Taking this further, Google and others such as Aligned and T5 are beginning to release tools that can show a more granular breakdown of energy use by facility, showing a more accurate picture of renewable energy use hour by hour.

Companies are increasingly touting their Water Usage Effectiveness (WUE) – a ratio which divides the annual site water usage in liters by the IT equipment energy usage in kilowatt-hours (KwH) – to illustrate how little water their facilities use.

Carbon Usage Effectiveness (CUE) aims to measure CO2 emissions produced by the data center and the energy consumption of IT equipment.

Schneider Electric recently published a framework document designed to help data center companies to report on their environmental impact, and assess their progress towards sustainability. The paper goes beyond the industry's normal focus on PUE and sets out five areas to work on across 23 metrics.

“Environmental sustainability reporting is a growing focus for many data center operators," Pankaj Sharma, EVP of Schneider's secure power division, told DCD at the time. "Yet, the industry lacks a standardized approach for implementing, measuring, and reporting on environmental impact.

Amongst those 23 metrics, Schneider includes greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (across Scopes 1, 2, and 3); water use, both on-site and in the supply chain; waste material from data center sites generated, landfilled, and diverted; and even species abundance to measure biodiversity in the surrounding land.

In 2020 the Swiss Datacenter Efficiency Association launched the SDEA Label, which aims to rate a facility’s efficiency and climate impact in an ‘end-to-end’ way; taking into account not only PUE but also infrastructure utilization and the site’s overall energy recycling capabilities.

Despite the competition from young upstarts, PUE is still seemingly the top dog of sustainability metrics for now.

“In Harlow, we operate at industry-leading levels of efficiency, and we use PUE to help us monitor, measure, and optimize our customers’ energy footprints,” says Kao’s Thibault.

“We are aware of ITUE and TUE, but believe that PUE still offers our industry a widely adopted metric that can be used by new and legacy data centers to understand their energy requirements, to optimize their ITE environments, and reduce waste.”

“One might arguably say that our industry has been too focussed on PUE, [but] alternative metrics will require greater data, parameters, and discussion between operators and customers in order to define new standards and drive adoption. Many legacy operators also may not have the means to achieve anything further than improving PUE levels, which is another consideration for our industry. Until that level of granularity is available, PUE remains the best option.”