Atos this week delayed the approval of its 2023 financial report until the end of the year, as the beleaguered IT services giant continues work on a restructuring plan that could end its financial woes.

Faced with a mountain of debt, the French company has been working on a recovery plan, and said in a market update that delaying the report will help create a stable environment for discussions with stakeholders.

The French government has also promised to step in and help one of its most important businesses, pledging to buy assets worth €1 billion ($1.07bn) from Atos, a cash injection which could help the company stay afloat.

Other interested parties are also circling, with Atos said to have received four bids for different parts of its operation in the last month, including one from Daniel Kretinskiy, the Czech billionaire who had previously been in talks to acquire the Atos Tech Foundations business unit.

But how did Atos get into this situation? In the last issue of DCD Magazine, we took a look at the demise of one of European IT's biggest names, and considered what the future might hold for the business.

The house that Breton built

Given that he built a reputation as France’s premier magicien when it comes to turning around failing businesses, it is perhaps no surprise that Thierry Breton is not keen to be associated with the problems that have beset Atos.

Breton, now European Commissioner for the internal market, made his name in the 1990s by successfully waving his magic wand over a trio of struggling state-backed French organizations - national computer maker Groupe Bull, consumer electronics vendor Thomson, and telco France Telecom - and steering them back to profitability.

For a long time, it appeared Breton had also pulled a rabbit out of his hat at Atos. Taking over as CEO in 2009, he helped grow the company into a business of national strategic importance in France, providing digital infrastructure and services to clients across Europe and beyond. Annual revenue at Atos, which was €5.6bn ($6bn) in 2009, had doubled to €11.5bn ($12.5bn) by the time Breton departed for Brussels a decade later.

But since 2019, life at Atos has more closely resembled one of the rides at another of Breton’s projects, Paris theme park Futuroscope (he was part of the team that originally designed the park in 1986). The company’s share price has dipped more sharply than the scariest of rollercoasters amid a series of strategic blunders and a mounting pile of debt, with its market cap falling from €8.2 billion ($8.8bn) at the end of 2020 to just over €190 million ($312m) at the time of writing.

The company’s financial results for 2023, released at the end of March did not make for pretty reading, showing a record annual loss of €3.44 billion ($3.73bn), up from €1bn ($1.08bn) in 2022.

Distancing himself from Atos’s struggles, Breton reportedly told members of France’s financial press association at a meeting in March that he has “no responsibility, zero,” for Atos’s travails, saying they started after his departure. Bloomberg reported that the 69-year-old went even further, with his team issuing a three-page document outlining the wrong turns taken by the company, including the names of the CEOs in charge at the time.

Wherever the finger of blame lays - and for several politicians and shareholders, it is firmly pointed in Breton’s direction for laying shaky foundations that have caused the current problems - it is clear that Atos is facing a potentially existential threat. And even if it does survive, one of France’s biggest technology companies will never be the same again.

Cracks in the (Tech) Foundations

Atos was founded in 1997 when two French IT businesses, Axime and Sligos, merged. In 2000 it joined forces with Dutch tech vendor Origin to form Atos Origin (the Origin part of the name was eventually dropped in 2011) and began a period of rapid growth driven by a series of acquisitions.

It snapped up the UK and Netherlands consulting arm of KPMG in 2002, and two years later acquired SchlumbergerSema, Schlumberger’s IT infrastructure division. Following Breton’s appointment, Atos got even bolder, paying €850 million ($925m) for Siemens’ IT business, and expanding into the US through the purchases of Xerox IT outsourcing (€918 million) and a similar company Syntel, for which it paid €3.1bn ($3.5bn) in 2018. Along the way, it added one of Breton’s former companies, Bull and its supercomputing expertise, for good measure.

The result was a business that, at its 2017 peak, was deriving the majority of its income, some €7 billion ($7.6bn) annually, managing digital infrastructure. It operates five of its own data centers according to Data Center Platform, three in France and one each in Austria and Germany.

So where did it all go wrong? “With these companies, it can often take a long time for the rot to set in and for it to be visible when the problems were already there,” says James Preece, principal analyst at Megabuyte. “Atos is a long-standing business and in my mind just made a few strategic missteps.

“They are probably perceived as a legacy service provider and were slower than others to transition into the world of cloud computing and digital services. On top of that, they’ve paid a lot for assets that they’ve struggled to get value from.”

Indeed, with such high exposure to managed infrastructure, it is perhaps understandable that Atos was hit harder than most by the advent of cloud computing and the willingness of businesses to embrace IT delivered as a service via the hyperscale public cloud platforms.

Atos did not help itself with an aborted attempt to buy DXC, a company similarly invested in outdated on-premises systems. It saw a $10bn take-over bid rejected by the US vendor in 2021 and walked away from the deal, but not before its share price had taken a battering as puzzled investors questioned the value of adding another legacy business to its portfolio. Later that year, $1 billion was wiped off the company’s value after accounting errors were discovered.

Breton has pointed to the fact that Atos was one of the first companies to partner with Google Cloud to offer private cloud services as evidence that, under his stewardship, Atos was heading in the right direction. But by summer 2021 the company was in the doldrums and, with revenue flatlining, its directors decided to take radical action, announcing it would slice its business in two, with its legacy managed infrastructure business renamed Tech Foundations, and cloud, cybersecurity and big data divisions rebranded as Eviden. Both companies, it was said at the time, would be publicly traded and operate separately under the Atos umbrella.

The business split that never was

The planned split was a sensible idea says Christopher Wiles, senior director analyst at Gartner. “The services they put into Tech Foundations are those focused on the cost, delivered via automation, process efficiencies, and offshore delivery models like data center and workplace,” Wiles says. “They have put what I'd call the more value-focused technologies, supporting cloud and cloud migration, big data, data analytics and cybersecurity, into Eviden.

“I can understand why they split it that way, there are a lot of parallels with the IBM and Kyndryl separation though not necessarily their reasons for doing it.”

Kyndryl is the ITSP formed when IBM spun off its managed services division in 2021. After struggling to make in-roads initially, its share price has been steadily climbing in recent months on the back of a series of contract wins and partnerships signed with the hyperscale cloud providers.

Any thoughts that Tech Foundations might do similar have been quashed by the fact that, well, the split hasn’t happened yet. Despite now operating as separate brands, Eviden and Tech Foundations remain two sides of the same coin and Atos has spent much of the last three years struggling to come to terms with its debt, which has mounted as income fell. The company has loans of €3.65 billion ($3.9bn) maturing in 2025, and has been forced to consider drastic action. This included potentially selling part of its prized BDS business unit, a part of Eviden which covers cybersecurity, to Airbus in a deal that would’ve brought in €1.8 billion ($2bn). However, the companies announced in March that talks between them had stalled and the deal was off.

Tech Foundations is also up for sale, and last year, a deal was agreed to sell the business in its entirety to EPEI, an investment fund run by Czech billionaire Daniel Kretinskiy. Under the agreement, Atos would have received €100 million ($108m) and unburdened itself of debt of €1.8bn. Kretinskiy also promised to participate in a €900 million ($980m) share issue to raise funds for Eviden.

But in November Atos revealed it was seeking to renegotiate its deal with EPEI, apparently to try and squeeze a few more Euros out of Kretinskiy. This did not go well, and in February the two companies said the take-over was off, with the Eviden fundraising canceled too.

Churn in the boardroom probably hasn’t helped. Atos is onto its fourth CEO in three years, with current incumbent Paul Saleh taking on the job in January, replacing Yves Bernaert, who himself had only been in post since October 2023. Bernaert said his departure was driven by a “difference of opinion on the governance to adjust and execute the strategy.” Atos chairman Bernard Meunier, one of the prime movers behind the split plan, also left the company last year.

Megabuyte’s Preece said dividing the business was “a massive undertaking” for Atos. “If you announce something like that, you need to make sure you can make it happen because you’ve told the world about it,” he says. “If it doesn't go exactly to plan, then you're going to find yourself in a world of pain.”

Macroeconomic factors outside the company’s control haven’t helped, Preece adds. “Market conditions significantly deteriorated after that announcement, through no fault of their own,” he explains. “So they tried to do all this logistical work around creating two separate entities and manage an underperforming business, at the same time as the markets were collapsing around them.”

What does the future hold for Atos?

Atos has appointed a mandataire ad hoc, or independent broker, to negotiate with its banks in a bid to refinance some of its debt and buy the company some much-needed breathing space.

Saleh said the company is “in discussions with our financial creditors with a view to reaching a refinancing plan by July within the framework of an amicable conciliation procedure.”

Digital consultancy OnePoint, which holds 11 percent of Atos shares, has offered to step in with additional funds if necessary according to its CEO David Layani. The Atos board says it has yet to consider or approve such an intervention.

The French government is also closely monitoring the situation, with 10,000 Atos staff based in France. The company also holds a string of public sector contracts; it is a major IT supplier to the French armed forces, and its infrastructure underpins France’s nuclear industry through its Bull supercomputing subsidiary. It is also a technology partner of the International Olympic Committee, meaning it will be responsible for providing much of the digital infrastructure underpinning the 2024 Summer Olympic Games, being held in Paris.

For Beatriz Valle, senior analyst at GlobalData, disposing of Tech Foundations - or making some potentially painful decisions - will be key to Atos forging a profitable future. “The problem with the [Tech Foundations] part of the business is that nobody is bidding against Atos for those legacy outsourcing contracts because they don’t make any money,” Valle says. If Atos ends up retaining Tech Foundations, she adds, it may be forced to cut a large number of jobs to reduce costs.

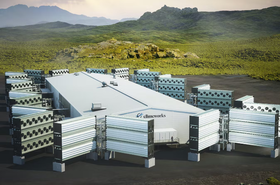

Valle believes Atos can flourish providing it trades off its strengths in areas like high-performance computing. It has scored a string of contracts with the EuroHPC joint undertaking, the European Union’s supercomputing project, and two machines backed by EuroHPC and based on Eviden’s BullSequana XH3000 direct liquid-cooled architecture - the Leonardo supercomputer in Italy and the MareNostrum system at the Barcelona Supercomputing System - featured at positions five and eight respectively in the latest Top500 list of the world’s fastest computers.

Eviden has also been awarded a €500 million ($525m) contract to develop Jupiter, Europe’s first exascale machine, which will be based in Germany.

“Atos needs to leverage what they’re good it, which is the HPC business, and try and sell HPC as a service, packaging that for the new AI world,” Valle says. “They don’t have the expertise that a company like IBM has in AI, but they could do something like that through partnerships, and leverage the compliance knowledge they have to offer a ‘sovereign cloud’ product for European companies.”

Gartner’s Wiles also believes Atos remains “a strong player in infrastructure services,” and says “those capabilities haven’t changed.” He explains: “It's not necessarily whether they've got the capabilities that people are worried about, it's the ramifications of their financial situation.”

Wiles says businesses he has spoken to that use Atos products and services are “looking at risk mitigation strategies” in case it goes into debt protection measures equivalent to the Chapter 11 bankruptcy process in the US. “The concern level of our clients [about Atos] has been raised since the turn of the year,” Wiles says. “Nobody is acting yet, but people are putting plans in place.”

This illustrates the precarious position the company finds itself in, and Megabuyte’s Preece says any further missteps could have a potentially devastating impact. “Atos, in its entirety, is burning cash at north of €1bn a year and it has €5bn of debt,” he says.

“You can see the writing is on the wall - they are running out of cash, and they need either flexibility from lenders on refinancing or a big transaction to cover a significant chunk of the debt they need to pay off in the next year. They’re fighting a lot of fires.”