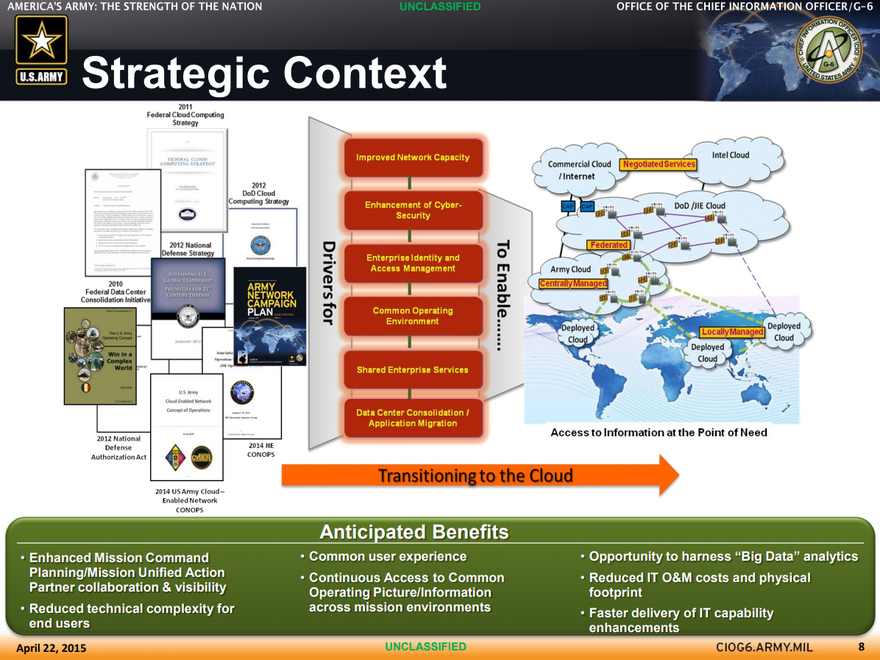

In an increasingly complex and changing world, the US Army is facing more challenges than ever: a rising China, a creative Russia, a wayward North Korea and, perhaps the most difficult of them all - legacy infrastructure.

Faced with overhauling decades of IT buildup and consolidating its data centers, the largest military the world has ever known has struggled, and is behind schedule despite several new initiatives. Here, the private sector eyes an opportunity with huge, multi-year contracts up for grabs.

Fighting for a large slice of this pie is IBM, a company with deep ties to the US government and a significant share of the cloud market.

IBM employs 29 senior client partners to work on its largest and most complex contracts, and only one of them focuses on federal public sector deals - Robert Kleppinger.

Under his purview is the Department of Defense, US Army, and the US Marine Corps; during his tenure the company has signed deals with the army to host a private cloud, and recently won a renewed contract with the military’s logistics division in a deal worth $135 million, this time adding ‘cognitive computing’ platform Watson to the mix.

These contracts are large, but Kleppinger told DCD that this is just the start. Watson, it seems, is prepared to go to war.

Soldiers and fortune

Back in 2012, IBM nabbed the contract to provide cloud services to the US Army’s Logistics Support Activity (LOGSA) division in a deal it claimed would save the military millions. “When we bid for this work, we bid for it as a managed service where IBM would come in, acquire all of the hardware and sell this computing-as-a-service. We established a private cloud and we took ownership of all of the hardware, we bought new hardware, and we’ve since refreshed it all,” Kleppinger said.

“And at the six month mark of that contract we began saving and cost-avoiding the US government about a million dollars a month. So if you look at the three and a half years we’re talking, it’s a significant amount of money that we have saved.”

According to Kleppinger, “the model proved so successful that the Army adopted it in their private cloud strategy and subsequently we won a contract last December, called Army Private Cloud Enterprise (APCE), which is also at Redstone. We have already established a private cloud for hundreds of customers across the Army and that’s part of its data center consolidation strategy.”

The deal to build and operate a data center at the Redstone Arsenal army post in Huntsville, Alabama, announced in January, is a three-year pilot scheme that could decide the future of the US Army’s cloud progress.

The Redstone data center replaces 11 Army-owned and operated facilities, but what the US Army learns from the pilot will affect its future consolidation plans for thousands of data centers.

Chief of enterprise architecture at the Army Architecture Integration Center, Col. Rodney Swann, explained at the ‘September Cloud Breakfast’ event held by the Armed Forces Communications and Electronics Association: “Once we get the Redstone kicked off and get lessons learned from that, that’s going to inform a lot of how we go forward in cloud computing.”

Kleppinger told DCD: “It’s the first. Their intent is to stand up several of these [data centers] - the number continues to change but we went under contract last December and we went live in March. We’ve now received our interim order to start migrating applications into the facility and have 167 applications that we will begin hosting this month.

“That’s three times, four times the size of what they expected at this point, so we’re doing quite well. The next phase of this will be to do another one. And right now a combination of NETCOM and the Army’s G-6/CIO are working that strategy, because it’s evolving, because things are moving faster than they thought they would.”

While it’s not clear what the US Army’s strategy is in the short term, the CIO Lt. Gen. Robert Ferrell has been clear about the end goal: “to reduce its hundreds of data centers by fiscal year 2025 to four enduring sites in CONUS [contiguous United States] and six abroad.”

The intentions behind the consolidation initiative are obvious - to save money, improve security and keep the military at the cutting edge of technology. Then-Secretary of the Army Eric Fanning said in late 2016: “During fiscal year 2015, the Army spent $8.3 billion on a wide range of IT products and services, including IT systems, applications, manpower, and host facilities. Many of these systems and applications are necessary for efficient operations; many are not.

“In addition, our systems and networks are under constant threat of compromise and disruption. Every IT system and application presents a potential attack surface to those wishing to affect our readiness to respond when required. We can no longer afford the luxury of unconstrained IT expenses nor accept the risk to the Army and the Nation posed by cyber threats directed against Army capabilities.”

And yet, the Pentagon has lagged behind other government departments in its consolidation efforts - and most of those departments are also behind schedule. As of December 2016, the Army has closed just 433 data centers. In an attempt to speed things up the Pentagon set up a data center consolidation team, while the Army launched the Army Application Migration Business Office (AAMBO) to help with moving applications to new computing environments.

“The strategy to consolidate is on track, but how to get there is not,” Kleppinger told DCD. “I think it depends on the customer - the Air Force is wedded to the public commercial cloud approach, the Army to keeping their cloud services on government premises, and most of that’s due to security. The Marine Corps is kind of both.”

It is with government on-premises data centers that Kleppinger sees IBM having an edge, due to “the higher level of security the Army wants, such as Impact Level 6 and above, which is really going to be hard to do in a commercial facility.”

IBM expects to achieve the Defense Information System Agency’s IL-6 rating at Redstone by early 2018. Some of the cloud providers are close behind, with Microsoft approved to IL-5 in January, and Amazon just this month.

While IBM’s approach may make it easier to achieve the highest rating, it’s not clear how much that matters to many in the government - the CIA has long had a huge contract with AWS (even after IBM tried to challenge the deal in court), and the US Air Force has frequently been touted as a key customer.

“When the Air Force looked at other cloud providers, none of them were able to immediately handle the compute scale while also meeting the DoD CC SRG IL-5 requirements,” AWS said in a press release announcing that the Air Force would use its servers to host the GPS OCX program, an ambitious (and also delayed) attempt to radically improve the Global Positioning Satellite network in partnership with Raytheon.

“Not only did AWS meet the Air Force’s needs, but the Air Force also experienced a 30 percent cost savings for storage cost.”

Enter Watson

But if higher level of security isn’t enough to attract custom, IBM thinks it has another lure - Watson, the machine learning algorithm that was launched into the public consciousness when it won Jeopardy! in 2011.

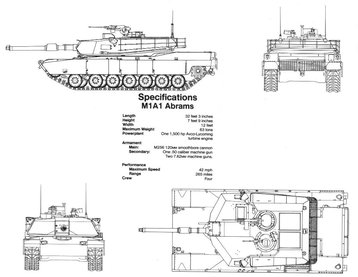

The company took on a project “to ingest all of the Stryker Combat System sensor data for the past 12 years - some thirty five hundred Strykers, and [we] were able to identify anomalies that occur through the aggregate,” Kleppinger said.

“We quickly began to predict failures of major components like transmissions and engines and steering systems and such before they actually happen.”

IBM claims Watson reads manuals, blueprints and even PS, The Preventive Maintenance Monthly, a comic book-style magazine, to learn what makes vehicles tick - and what makes them stop ticking.

It’s hard to evaluate such claims, and DCD must point readers towards an in-depth investigation by Stat into Watson’s struggle to live up to its promises in the healthcare market, but the trial on 10 percent of the Army’s Interim Armored Vehicle Stryker force appears to have proved successful.

As part of the larger cloud deal with LOGSA, IBM plans to integrate Watson deeper into the army’s logistics and maintenance operations.

“Ideally, the plan is to bring this further, probably next to aircraft, perhaps a combination of Apaches, Black Hawks and ultimately Chinooks. And do the M1 and M2 tanks, complete the Stryker work, and then move on into the engineering equipment,” Kleppinger said.

“There’s a lot of money spent in engineering equipment. You can kinda connect one to the other as we’re doing similar work right now at Caterpillar. We’ve learned a lot from doing this on commercial equipment with commercial customers.”

Kleppinger told DCD that IBM is doing similar work with the UK and French Air Force, as well as “some cognitive work with the Saudis.”

He added that “we do use Watson considerably in analyzing intelligence data from the intelligence community.” Exactly what this entails is, unsurprisingly, not public, but in 2013 The New York Times published a story claiming that the NSA and CIA had been trialling Watson for two years.

Watson “is precisely the technology that would make the ambitious data-collection program of the NSA seem practical. Computers could instantly sift through the mass of Internet communications data, see patterns of suspicious online behavior and thus narrow the hunt for terrorists,” the publication wrote.

Such deals, Kleppinger said, mark a chance for militaries around the world to modernize: “With regard to logistics and financial and things of that sort, I think cognitive is definitely the future. It’s the ability to predict, the ability to prepare better, the ability to see things that you wouldn’t normally see.

“Spreadsheets and analysts just can’t absorb and analyze the quantity of data that’s produced today. So the cognitive approach is going to be used by the US Army, but it’s also going to be global as far as other armies around the world are concerned.”

As for intelligence work: “Any time you have a human in the loop there’s risk. And so we’ve got to control that risk.”

But, while IBM hopes to keep humans out, its place in that loop is far from certain - Amazon, Microsoft, General Dynamics and others all want a piece of the consolidation pie, and the fight is only just getting started.