Last week, the sustainability news from Microsoft was not good - but I'm impressed with the company for reporting it. Microsoft has made one of the most ambitious promises in the industry - to be carbon negative by 2030 - but last year that process took a huge step backwards. And the problem was effectively out of Microsoft's control.

Last year, the emissions from Microsoft's supply chain grew by 23 percent. That amount sounds disappointing, but in fact, that growth utterly swamped all the improvements Microsoft has made in reducing its direct emissions in recent years.

The emissions were produced by companies outside of Microsoft, and the growth was entirely due to Microsoft's success

The Catch-22 of Scope 3

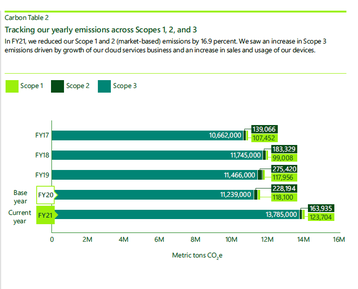

Look at the graph, from Microsoft's 2021 sustainability report (the latest report goes on this link, each year). The emissions produced in generating electricity for Microsoft's data centers, the part we regularly cover at DCD, is covered by the black strip on each bar. That's the Scope 2, or indirect, part of its footprint. The emissions caused directly by Microsoft, in its offices and promises (Scope 1), is the smaller, light green, strip

But these are a drop in the ocean, compared with the company's overall footprint. Together, those strips are dwarfed by the dark green bar, which is the emissions from Microsoft's supply chain, both upstream and downstream. These Scope 3 emissions are some 50 times bigger than the Scope 1 and 2 emissions, which are under Microsoft's direct control.

Scope 3 includes the the concrete used in buildings, the embodied emissions in equipment the company purchased, the emissions used in delivering physical products, and the energy used by Xboxes and other devices in the home.

And here's the tragic part During 2021, despite Microsoft's commitment to cutting its total emissions, its Scope 3 readings went up massively. And the reason was simply that its business boomed.

The trouble with Scope 3 is it is almost automatically increased by business success.

During the pandemic, people bought more Xboxes, and played on them for longer, using their domestic electricity. Microsoft may have bought a green tariff for its data centers, but most of its customers haven't so those Xboxes generated millions of tons of CO2.

They also used more cloud services. As well as games and entertainment, there was Teams and other business services. To meet that need, Microsoft has embarked on a continuing surge of data center building.

"This year’s report includes several important lessons," said Brad Smith, President and Vice Chair, and Lucas Joppa, Chief Environmental Officer The company's goal of getting its Scope 1 and Scope 2 emissions to zero is achievable. But addressing Scope 3 is way harder. The company has a goal of ordering its suppliers to cut their emissions by 50 percent, and then, the pair say, "we’ll rely on carbon removal to reach carbon negative".

Let's unpack that. Firstly, if Microsoft aims to get suppliers to reduce their carbon emissions, that sounds like an ultimatum: cut CO2 or lose your contract with Microsoft. Only a company the size of Microsoft can think of doing that - and we can see from the figures that it's not getting very far as yet.

Secondly, even if Microsoft does reduce its supply chain emissions by 50 percent, how much carbon removal will it have to buy? Well, this year's Scope 3 emissions were nearly 14 million tons of CO2. Microsoft this year bought the removal of a million tons of CO2, from a combination of projects including biochar creation, and direct air capture by Climeworks. At the moment, Climeworks charges $1250 per ton for CO2 rfemoval, so removing seven million tons of CO2 at today's prices would cost nearly $9 billion - something like one-seventh of its yearly profits.

There are some caveats to this of course. For one thing, with customers like Microsoft, it's possible that the scale of carbon removal will increase rapidly, and prices will come down.

But also, nowhere in Microsoft's environmental plans, does the company plan to shrink.

Growth is a problem?

This is going to be a big problem with Scope 3 emissions. They are closely tied with the growth of the company. It is very hard to imagine a company reducing its Scope 3 emissions while growing rapidly. And Microsoft's plan to be carbon negative is coupled with - and potentially at odds with - a plan for continued growth, cashing in on the current boom in data center demands.

Of course, it's unfair to single out Microsoft here. Google and AWS have equally big problems - or at least they would do, if they had made Microsoft's ambitious gesture. Google tracks its Scope 3 emissions in its sustainability report, but hasn't made such a bold plan, while AWS is aware of Scope 3 but doesn't break it out or make promises about it, as far as we can tell.

And there is a serious potential downside to these promises, and the difficulty of meeting them. Because an ambitious promise involves a level of risk.

This week, the US Security and Exchange Commission (SEC) unveiled plans to make CO2 emissions part of its mandatory report structure. This means that companies large enough to register with the SEC will have to disclose their direct and indirect emissions. And those who have made promises about Scope 3, may also have to disclose their Scope 3 emissions.

The SCE says it has to include these emissions in mandatory reports, because companies who fail to meet environmental targets, including Scope 3 reductions, may suffer loss of business.

Of course, loss of business means people avoiding a company failiing to meet its green targets.

Ironically, that loss of business might reduce the emissions in the supply chain, and cut Scope 3 emissions, making it likely that the company could meet its targets.

Alternatively, is it time for companies to address the tension between financial growth and emissions reduction?