During a few months this summer, parks and green spaces in cities across the world were virtually unusable. Those wishing to walk a dog or simply take a pleasant stroll found the area strewn with human statues, motionless bar the odd flick of a thumb. Very occasionally, a figure would move a few paces, before resuming their frozen form.

This was not the end times, a Black Mirror advert, or some form of bizarre religious practice. But it was something close - Pokémon Go had just released and, for some reason, the world had gone mad.

Headlines blared with tales of dead bodies uncovered, memorials desecrated and cars crashed as players were unable to tear themselves away from the game. Reporters found ways to cram Pokémon into any article, politicians used it as a cheap campaign tool, and smartphone batteries drained in their millions.

The real action, however, was not taking place on these phones, or even on the stock market where Nintendo’s shares rose and fell over confusion about whether the company had actually developed the game.

No, the true madness was taking place on the cloud.

Phenomenoff

“We didn’t have any idea what was going to happen. We thought we knew,” Phil Keslin, Niantic Labs CTO said at the Google Cloud Platform (GCP) Next London event DCD attended.

Niantic Labs formed as an internal startup within Google, aimed at exploring augmented reality and location based gaming.

Founded by John Hanke, the man behind Google Earth, Maps and Streetview, the company experimented with those ideas while under the umbrella of the search giant, releasing Go-precursor Ingress. But to truly fly, Niantic itself had to be released.

With Google aware that gaming companies were wary of doing business with a voracious tech giant, it spun Niantic out in 2015. In October of that year, Google, Nintendo and The Pokémon Company invested $30 million in the newly independent startup.

The developer then spent the next nine months forming its new creation, an augmented reality take on the beloved Pokémon franchise. Excitement remained high from the announcement, but Pokémon Go, released in waves starting on July 6th, was soon to outperform even their wildest of hopes.

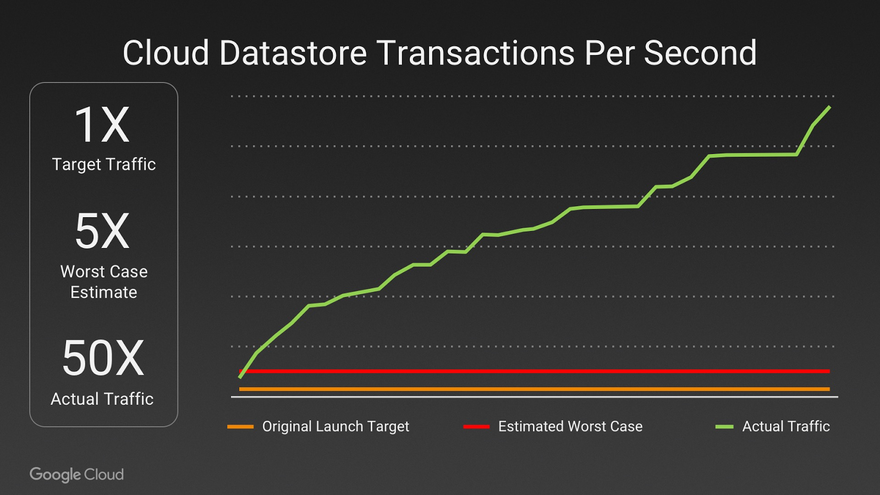

At Next, Keslin brought with him a chart showing just how wrong the company’s expectations had been.

“The bottom line is where we expected we would be, the second line is our worst case, and that’s what we provisioned for within Google Cloud, and the green line is our rocket ship,” Keslin said.

He added: “You’ll notice that we don’t start below our expected line, and that was Australia and New Zealand. Australia and New Zealand were supposed to be four percent of our total traffic at the expected line, and we ended up at 50 percent of our worst case after day one.”

It took just six hours for Niantic to realize its error. “In fact, the engineering manager for the Pokémon Go team sat in the staff meeting and described where we thought the number was going to be, and he presented the number and all the jaws at the table dropped,” Keslin said.

While John Hanke expressed disbelief that the game could prove that popular, that quickly, Keslin said that he believed it would triple the engineering manager’s prediction. “And we’re actually above that point on this graph,” he commented.

“This graph represents what happened with Data Store. But this was happening everywhere. This was going on Compute, Big Table, Big Query. Everything was blowing up when this was happening,” he said.

“This is what we had to deal with, it was a hairs-on-fire experience and, thanks to Google, we actually survived. What we don’t talk about often was that the team that made this happen was four engineers on the Pokémon Go side. Needless to say, we didn’t get a whole lot of sleep during this time.”

Google, whose cloud platform was integral to the operation of the game, had been equally blindsided by the surge of popularity for the freemium mobile title. “We provisioned extra capacity for them, because we kind of thought like 5, 6, 10x [what they asked for], which is what we did,” Brian Stevens, VP of Product, Google Cloud Platform, said.

“But still, it blew through that really quickly too.”

He continued: “I remember when the email came in from Sundar [Pichai], our CEO, that ‘hey we need to jump on this thing and give them some help,’ and I’m like ‘what the hell is Pokémon Go?’ The first thing I did was download the game, went out my backyard, caught one, and then ran back inside and got back to work.”

Niantic became the first customer to benefit from Google’s new Customer Reliability Engineering team, where technical Google staff work with customers to help keep cloud products online.

“Google CRE turned up day two and it was really helpful,” Keslin said. “Having a Google Hangout with a group of SREs and product managers and engineers, all there to support the four engineers on our side. I think at one point we had 40 people all participating in these Hangouts to ensure that we got what we needed.

“We knew that we had people on Google’s side that were reprovisioning resources to get us to where we are today. We knew it was going to take a little bit of time, but they were there to help us, and that was fantastic. That saved our bacon.”

Conspicuously unmentioned at the Next event was the fact that Pokémon Go did, in fact, fail quite a lot during the first few weeks and months after launch, often rendering the whole thing unplayable.

The greater message, it seemed, was not that attendees should be impressed that Google was able to keep the product online the whole time. Rather, given the immense level of demand that they could not have predicted, the message was that we should be impressed that Google was able to keep the product online at all.